Pub history

The Wrong ’Un

Cricket has been a favourite local pastime for more than two centuries. There are references to Bexley men playing cricket in 1746. One of the most difficult deliveries for a batsman to play is the googly, or wrong ’un, bowled by a leg spinner.

234–236 The Broadway, Bexleyheath, London, DA6 8AS

Cricket has been a favourite local pastime for more than two centuries. There are references to Bexley men playing cricket in 1746. One of the most difficult deliveries for a batsman to play is the googly, or wrong ’un, bowled by a leg spinner.

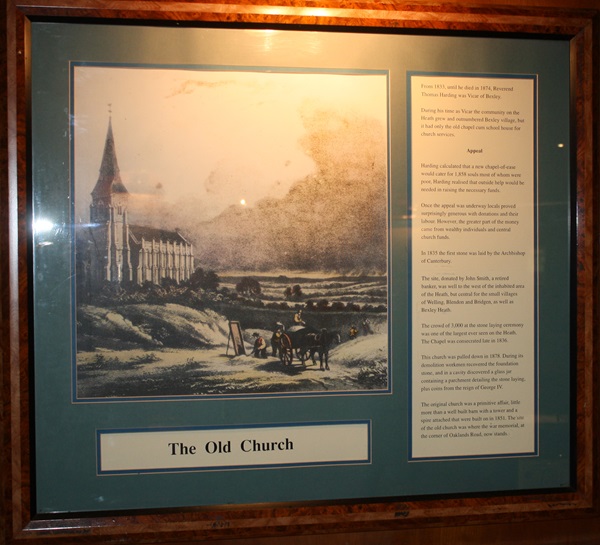

A print and text about the old church.

The text reads: From 1833, until he died in 1874, Reverend Thomas Harding was Vicar of Bexley.

During his time as Vicar the community on the Heath grew and outnumbered Bexley village, but it had only the old chapel cum school house for church services.

Harding calculated that a new chapel-of-ease would cater for 1,858 souls most of whom were poor, Harding realised that outside help would be needed in raising the necessary funds.

Once the appeal was underway locals proved surprisingly generous with donations and their labour. However, the greater part of the money came from wealthy individuals and central church funds.

In 1835 the first stone was laid by the Archbishop of Canterbury.

The site, donated by John Smith, a retired banker, was well to the west of the inhabited area of the Heath, but central for the small villages of Welling, Blendon and Bridgen, as well as Bexley Heath.

The crowd of 3,000 at the stone laying ceremony was one of the largest ever seen on the Heath. The Chapel was consecrated late in 1836.

This church was pulled down in 1878. During its demolition workmen recovered the foundation stone, and in a cavity discovered a glass jar containing a parchment detailing the stone laying, plus coins from the reign of George IV.

The original church was a primitive affair, little more than a well built barn with a tower and a spire attached that were built on in 1851. The site of the old church was where the war memorial, at the comer of Oaklands Road, now stands.

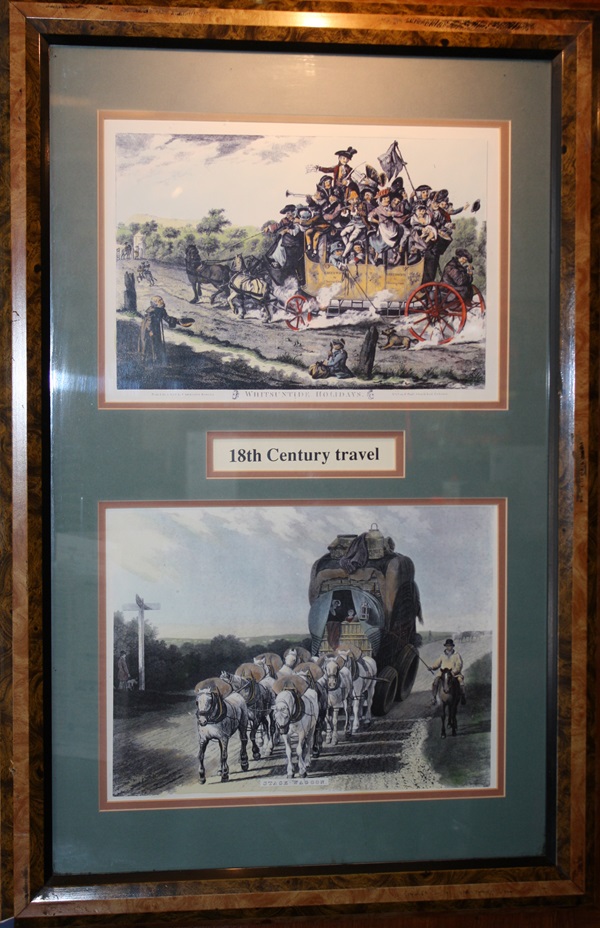

Prints of travel in the 18th century.

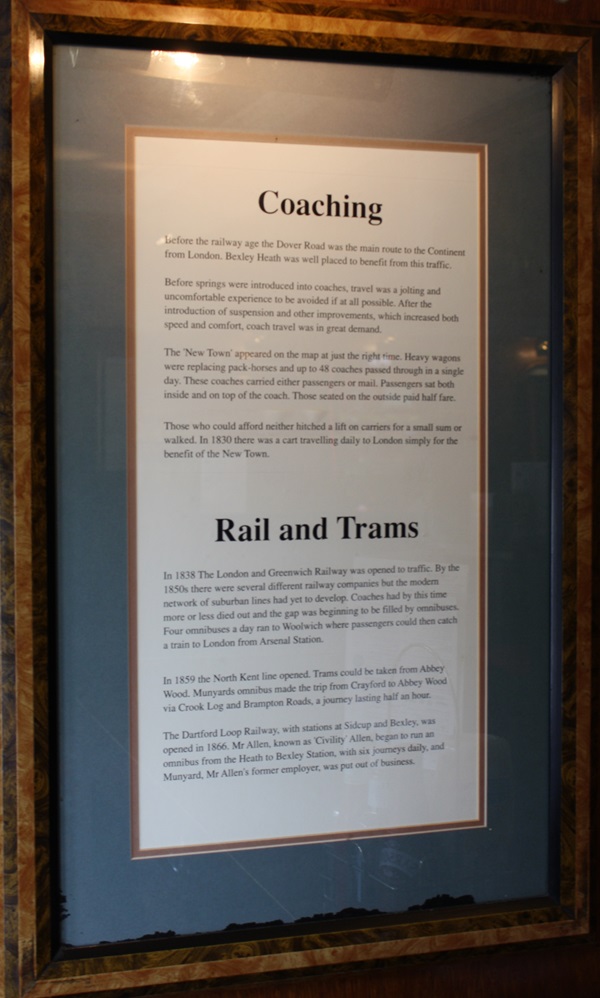

Text about transport in Bexleyheath.

The text reads: Coaching

Before the railway age the Dover Road was the main route to the Continent from London. Bexley Heath was well placed to benefit from this traffic.

Before springs were introduced into coaches, travel was a jolting and uncomfortable experience to be avoided if at all possible. After the introduction of suspension and other improvements, which increased both speed and comfort, coach travel was in great demand.

The ‘New Town’ appeared on the map at just the right time. Heavy wagons were replacing pack-horses and up to 48 coaches passed through in a single day. These coaches carried either passengers or mail. Passengers sat both inside and on top of the coach. Those seated on the outside paid half fare.

Those who could afford neither hitched a lift on carriers for a small sum or walked. In 1830 there was a cart travelling daily to London simply for the benefit of the New Town.

Rail and Trams

In 1838 The London and Greenwich Railway was opened to traffic. By the 1850s there were several different railway companies but the modern network of suburban lines had yet to develop. Coaches had by this time more or less died out and the gap was beginning to be filled by omnibuses. Four omnibuses a day ran to Woolwich where passengers could then catch a train to London from Arsenal Station.

In 1859 the North Kent line opened. Trams could be taken from Abbey Wood. Munyards omnibus made the trip from Crayford to Abbey Wood via Crook Log and Brampton Roads, a journey lasting half an hour.

The Dartford Loop Railway, with stations at Sidcup and Bexley, was opened in 1866. Mr Allen, known as ‘Civility’ Allen, began to run an omnibus from the Heath to Bexley Station, with six journeys daily, and Munyard, Mr Allen’s former employer, was put out of business.

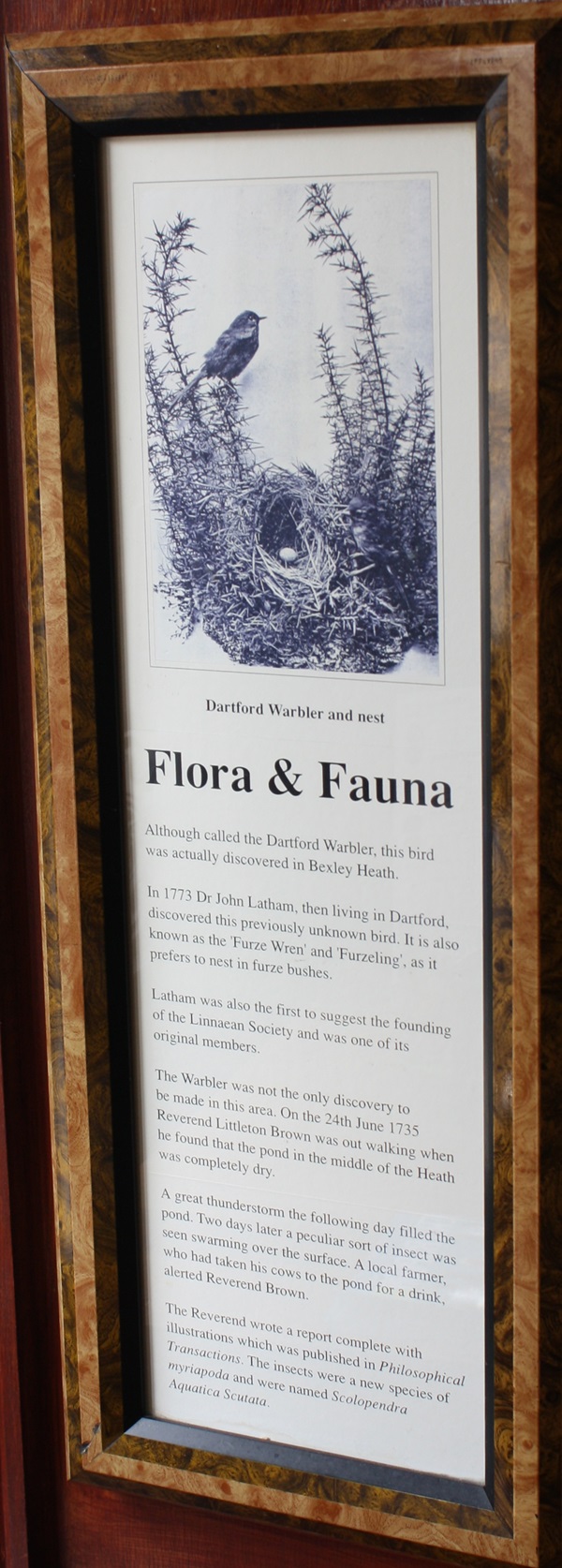

A photograph and text about the Dartford Warbler.

The text reads: Although called the Dartford Warbler, this bird was actually discovered in Bexley Heath.

In 1773 John Latham, living in Dartford, discovered this previously unknown bird. It is also known as the ‘Furze Wren’ as it prefers to nest in furze bushes.

Latham was also the first to suggest the founding of the Linnaean Society and was one of its original members.

The Warbler was not the only discovery to be made in this area. On the 24th June 1735 Reverend Littleton Brown was out walking when he found that the pond in the middle of the Heath was completely dry.

A great thunderstorm the following day filled the pond. Two days later a peculiar sort of insect was seen swarming over the surface. A local farmer who had taken his cows to the pond for a drink alerted Reverend Brown.

The Reverend wrote a report complete with illustrations which was published in Philosophical Transactions. The insects were a new species of myriapoda and we’re named Scolopendra Acquatica Scutata.

Text about early development in Bexleyheath.

The text reads: The Saxons

In 457AD the Saxons arrived. Led by Hengist they fought the Britons at the Battle of Creccanford (Crayford). Some 4,000 lay dead by the time victory was achieved.

Hengist styled himself King of Kent. He occupied Crayford and his army camped on Bexley Heath, guarding the London Road against the possible return of the Britons who had fled to the capital.

Two Saxon communities known as ‘tuns’ were established. On the north side of the London Road the settlement was called Brampton and on the south side it was known as Upton.

The name Bexley is Saxon. In ancient documents it is spelled Bixle or Bekesley. Bek means ‘a brook’ and ‘ley’ is an open meadow. Therefore the plain name of Bexley is in fact something much more descriptive: ‘the pasturelands beside the stream.’

This is exactly what greeted the Saxon invaders when they established their first camps in the valley with the River Cray running through it.

The Middle Ages

During the Middle Ages pilgrims gathered on the Heath on their way to the shrine of Thomas Beckett in Canterbury Cathedral. They assembled on the Heath to form a procession before entering Crayford prior to their first night’s stop over at Dartford.

However in 1381 there was a very much larger gathering with a very different purpose. Some 100,000 peasants marched across the Heath towards London led by Wat Tyler in protest at the Poll Tax and demanding an end to the slave-like conditions under which they lived.

The old manor of Bexley was one of the great estates of the kingdom. It included what is now Welling, Bexley, Lamorby and Bexley Heath. Sir William Camden, the great antiquary was Lord of the Manor in the early part of the 17th Century. In his will he made over the estate to Oxford University in order to establish a professorship in history. The University leased the estate to a succession of ‘tenants-in-chief’.

A photograph and text about The House on Wheels and Market House.

The text reads: An Early Mobile Home

John Dann leased the Bexley Heath windmill in 1830. According to local tradition as his family grew he built another house next to the mill.

The house was built of wood and had axles so that wheels could be attached and the house pulled to another location. This was a shrewd move as an ordinary house built on foundations was freehold and rateable, but rates were not payable on ‘temporary’ accommodation.

John Dann acquired 62 Woolwich Road in 1816, and the wooden house on that site, which is believed to be the original ‘house on wheels’ moved to this address in 1838.

The removal of the house to this site at a later date is also recalled. Local residents told a story of how at two o’clock one morning in 1885 the house was seen mounted on cart wheels being pulled by 12 horses travelling from the Mill to Woolwich Road. The roof had been removed, and was put back in place when the house reached its destination.

The Market House

Probably the oldest surviving building on the Heath is the Market House. It stands beside the Clock Tower where May Place Road intersects the Broadway. The building was built around 1831 by Oswald Smith, nephew of the banker John Smith. It cost £1000, which was then a considerable sum. It contained fourteen spaces for traders.

By 1835 it was let to William Clark, who had a busy grocery business and wanted to expand. Clark called his new premises ‘The Emporium’. When Smith auctioned the site in 1844, William Clark bought it. He ran his ‘Emporium’ until 1855, after which it was used as a Congregational Sunday School, mineral water factory, and a motor service station.

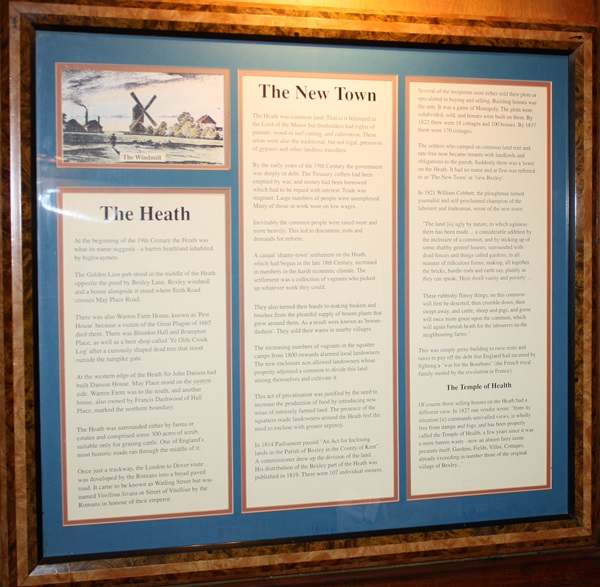

A print and text about the history of Bexleyheath.

The text reads: The Heath

At the beginning of the 19th century the Heath was what its name suggests – a barren heathland inhabited by highwaymen.

The Golden Lion pub stood in the middle of the Heath opposite the pond by Bexley Lane. Bexley windmill and a house alongside it stood where Erith Road crosses May Place Road.

There was also Warren Farm House, known as ‘Pest House’ because a victim of the Great Plague of 1665 died there. There was Blendon Hall and Brampton Place, as well as a beer shop called ‘Ye Olde Crook Log’ after a curiously shaped dead tree that stood outside the turnpike gate.

At the western edge of the Heath Sir John Danson had built Danson House. May Place stood on the eastern side. Warren Farm was to the south, and another house, also owned by Francis Dashwood of Hall Place, marked the northern boundary.

The Heath was surrounded either by farms or estates and comprised some 300 acres of scrub, suitable only for grazing cattle. One of England’s most historic roads ran through the middle of it.

Once just a trackway, the London to Dover route was developed by the Romans into a broad paved road. It came to be known as Watling Street but was named Vitellina Strata or Street of Vitellius by the Romans in honour of their emperor.

The New Town

The Heath was common land. That is it belonged to the Lord of the Manor but freeholders had rights of pasture, wood or turf cutting, and cultivation. These areas were also the traditional, but not legal, preserves of gypsies and other landless travellers.

By the early years of the 19th century the government was deeply in debt. The Treasury coffers had been emptied by war, and money had been borrowed which had to be repaid with interest. Trade was stagnant. Large numbers of people were unemployed. Many of those in work were on low wages.

Inevitably the common people were taxed more and more heavily. This led to discontent, riots and demands for reform.

A casual shanty town settlement on the Heath, which had begun in the late 18th century, increased in numbers in the harsh economic climate. The settlement was a collection of vagrants who picked up whatever work they could.

They also turned their hands to making baskets and brushes from the plentiful supply of broom plants that grew around them. As a result were known as ‘broom dashers’. They sold their wares in nearby villages.

The increasing numbers of vagrants in the squatter camps from 1800 onwards alarmed local landowners. The new enclosure acts allowed landowners whose property adjoined a common to divide this land among themselves and cultivate it.

This act of privatisation was justified by the need to increase the production of food by introducing new areas of intensely farmed land. The presence of the squatters made landowners around the Heath feel the need to enclose with greater urgency.

In 1814 Parliament passed “An Act for Inclosing lands in the Parish of Bexley in the County of Kent”. A commissioner drew up the division of the land. His distribution of the Bexley part of the Heath was published in 1819. There were 107 individual owners.

Several of the recipients soon either sold their plots or speculated in buying and selling. Building houses was the aim. It was a game of Monopoly. The plots were subdivided, sold, and houses were built on them. By 1822 there were 18 cottages and 100 houses. By 1837 there were 170 cottages.

The settlers who camped on common land rent and rate free now became tenants with landlords and obligations to the parish. Suddenly there was a ‘town’ on the Heath. It had no name and at first was referred to as ‘The New Town’ or ‘New Bexley’.

In 1821 William Cobbett, the ploughman turned journalist and self-proclaimed champion of the labourer and tradesman, wrote of the new town:

“The land [is] ugly by nature, to which ugliness there has been made a considerable addition by the enclosure of a common, and by sticking up of some shabby genteel houses, surrounded with

dead fences and things called gardens, in all manner of ridiculous forms, making, all together, the bricks, hurdle-rods and earth say, plainly as they can speak. Here dwell vanity and poverty’…

These rubbishy flimsy things, on this common will first be deserted, then crumble down, then swept away, and cattle, sheep and pigs, and geese will once more graze upon the common, which will again furnish heath for the labourers on the neighbouring farms.”

This was simply gerry-building to raise rents and taxes to pay off the debt that England had incurred by fighting a “war for the Bourbons” (the French royal family ousted by the revolution in France).

Of course those selling houses on the Heath had a different view. In 1827 one vendor wrote: “from its situation [it] commands unrivalled views, is wholly free from damps and fogs, and has been properly called the Temple of Health; a few years since it was a mere barren waste now an almost fairy scene presents itself, Gardens, Fields, Villas, Cottages, already exceeding in number those of the original village of Bexley…”

Text about Doctor Goddard and Thomas Strong.

The text reads: Doctor Goddard

Dr Goddard became the vicar here in 1824. He founded the first school in Bexley Heath obtaining support from the “National Society for the Education of the Poor in the principles of the Established Church” to purchase the Dissenting Chapel on Mill Lane in 1826.

The Government did not make its first grant for public education until 1833. Education was not compulsory until 1878. Bexley’s first school was maintained by voluntary contributions, and by charging a fee of two pence per week.

Dr Goddard had his blind spots though. The child of Jack Smedley, a grocer and draper was christened with the unusual name ‘Annsir’.

Dr Goddard had asked the godmother for the child’s name and received the reply, “Anne, Sir”, and duly christened her Annsir.

On another occasion he forgot to have his haircut. Arriving at the church one Sunday he was suddenly aware of his appearance. The problem was that no-one was supposed to work on the Lord’s day. However he spotted Mr Cologne, the beadle and an old soldier who was also the local barber, and produced the following argument:

“Cologne, you know that the works of piety and necessity may be done of Sunday. It is impossible for me to preach with my hair like this. You must cut it”.

The logic was irresistible, Mr Cologne did his duty.

Thomas Strong’s Letter

Thomas Strong, a well-to-do local man, owned a substantial amount of land judging by the amount of rates he paid in 1813.

However, Strong objected to the parish forcing owners of cottages and small houses to pay rates. These people were poor, and the rates were almost entirely used to provide poor relief. In effect the poor were being bled to help those even worse off, whom they would soon join under this system.

In 1833 Strong published a letter pointing out that poverty was on the increase because employees, mainly farm labourers, were so badly paid. The average working man had four dependants to support. Low wages could not buy enough fuel. Hedges were scavenged for kindling wood and evenings spent in ale-houses to enjoy the welcome of a good fire.

Strong was quite sure about the solution, and tells his fellow land owners quite clearly: “Ponds might be cleansed (drinking water had to be reached by sinking deep wells because the surface water was unwholesome), lands repaired, roads made, trees planted, others grubbed, lands worthless improved, and labour found for every poor man in the parish”.

Strong was a member of the committee that ran the parish workhouse and outdoor relief (payments to the needy who had somewhere to live). He became sufficiently prosperous to purchase Woodville, the large house that later became Maryville Convent at Welling.

His views, as expressed in his letter, seem to anticipate those of the economist John Maynard Keyne which have been so influential in our own century.

Text about the history of the name Danson.

The text reads: The name Danson has several earlier forms, dating back to at least 1284 AD, the date of the earliest surviving record. The original name seems to be a compound of Dene – a little valley, sige – sunset, inga -people, tun – farmstead.

Densynton or Dansington, thus has the picturesque meaning: ‘the farm of the people in the little valley where the sun sets’. This would fairly accurately describe an Anglo- Saxon farmstead near the Danson stream. There is an alternative derivation which maintains that Denesige was an Old English personal name, and therefore Densynton meant “the farm of Denesige’s people”.

The area was possibly settled by followers of Hengist after the battle of Crecganford (Crayford), in 457 AD.

In the 13th century, surveys show that Densynton consisted of 17 acres and had been settled and farmed before the Normans came and began clearing land for cultivation. In the Middle Ages the manor of Bexley belonged to the Church. In the 1530s Henry VIII took nearly all church property for the Crown (known as the Dissolution) and then handed it out to his barons. Bexley was one of these manors. Mary Tudor briefly gave the church back its estates, but Elizabeth I reaffirmed her father’s annexation.

The Lords of the manors were tenants-in-chief who paid quit rent to the Crown. They could sub-let at a profit. In 1567 Dansington was sub-let to William Knightley, and then around 1600 to Richard Cowper.

The house at this time was probably nothing more elaborate than a small timber framed affair built by local workmen.

James I sold the whole manor of Bexley to John Spielman, the royal jeweller, who sold it on to William Camden. Camden gave the manor to Oxford University to found a professorship. The university were Lords of the Manor for 200 years.

The text reads: In 1695 it was sold to John Styleman as a gentlemen’s country seat. Styleman had made a fortune in India, and been Mayor of Madras.

He and his wife made improvements, before letting the property in 1723 to John Selwyn, MP for Gloucester. He had been aide-de-camp to the Duke of Marlborough, Churchill’s famous ancestor and the victor at the Battle of Blenheim. Selwyn spent £1,000 on Danson.

Selwyn died in 1750. John Styleman had died in 1734 and his widow, to whom he left the rental income from Danson, died in 1751. A London merchant, John Boyd, acquired the estate, and over the next 40 years added pieces of land round about as they came on the market. Eventually he owned 600 acres.

In 1753 he decided to put some of his wealth obtained largely from trade in sugar, into making Danson a stylish residence.

Robert Taylor was the architect. A new site was chosen for the proposed Palladian villa. During its construction Boyd’s wife died and he remarried. A new family was expected, so two wings were added to the original design.

By 1768 the new building was complete. The Park was landscaped by Fean Garwood, in the style of Capability Brown. A large area was flooded to make a great lake, which drowned the old Danson House, and the whole transformation was complete by 1773.

In 1807 the second Sir John Boyd sold the Danson Estate to John Johnston, a retired military man with interests in the stock exchange. His son Hugh Johnston, built Little Danson when he married, and then moved into the villa when his father died. It was Hugh who sold the famous Danson Vase to the British Museum.

In 1862 he sold Danson itself to Alfred Bean. The outlying parts of the estate were sold for housing, and by 1890 Mrs Bean retained just the Mansion, the Park and the Home Farm. She died in 1921, stating in her will that she wished her home to become a public park. Bexley Urban District acquired the estate of 200 acres in 1924, for £16,000. It was opened to the public in 1925 by Princess Mary King George V’s daughter.

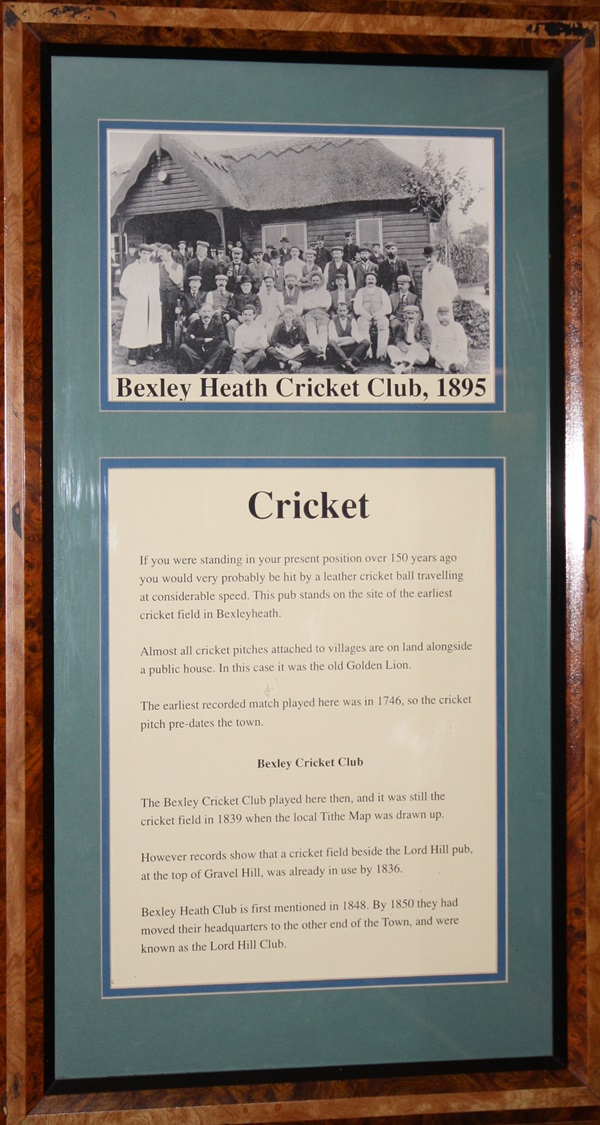

A photograph and text about cricket in Bexleyheath.

The text reads: If you were standing in your present position over 150 years ago you would very probably be hit by a leather cricket ball travelling at considerable speed. This pub stands on the site of the earliest cricket field in Bexleyheath.

Almost all cricket pitches attached to villages are on land alongside a public house. In this case it was the old Golden Lion.

The earliest recorded match played here was in 1746, so the cricket pitch pre-dates the town.

The Bexley Cricket Club played here then, and it was still the cricket field in 1839 when the local Tithe Map was drawn up.

However records show that a cricket field beside the Lord Hill pub at the top of Gravel Hill, was already in use by 1836.

Bexley Heath Club is first mentioned in 1848. By 1850 they had moved their headquarters to the other end of the Town, and were known as the Lord Hill Club.

A print of cricket in 1743.

Illustrations of cricket in 1787 and 1838.

A photograph of Market Place, Bexleyheath c1910.

A photograph of the Broadway looking east c1914.

A photograph of Market Place, Bexleyheath c1905.

A photograph of Market Place, Bexleyheath c1910.