Pub history

The Wheatsheaf Inn

This dates back to at least the 18th century and was one of the town’s main coaching inns. The inn was given a Georgian-style front in c1820. Scotland’s national poet, Robert Burns, is said to have frequented The Wheatsheaf. Burns knew Kilmarnock well. The very first edition of his poems was printed here in 1786. He is commemorated by a grandiose monument in Kay Park.

70 Portland Street, Kilmarnock, East Ayrshire, KA1 1JG

This dates back to at least the 18th century and was one of the town’s main coaching inns. The inn was given a Georgian-style front in c1820. Scotland’s national poet, Robert Burns, is said to have frequented the Wheatsheaf. Burns knew Kilmarnock well. The very first edition of his poems was printed here in 1786. He is commemorated by a grandiose monument in Kay Park.

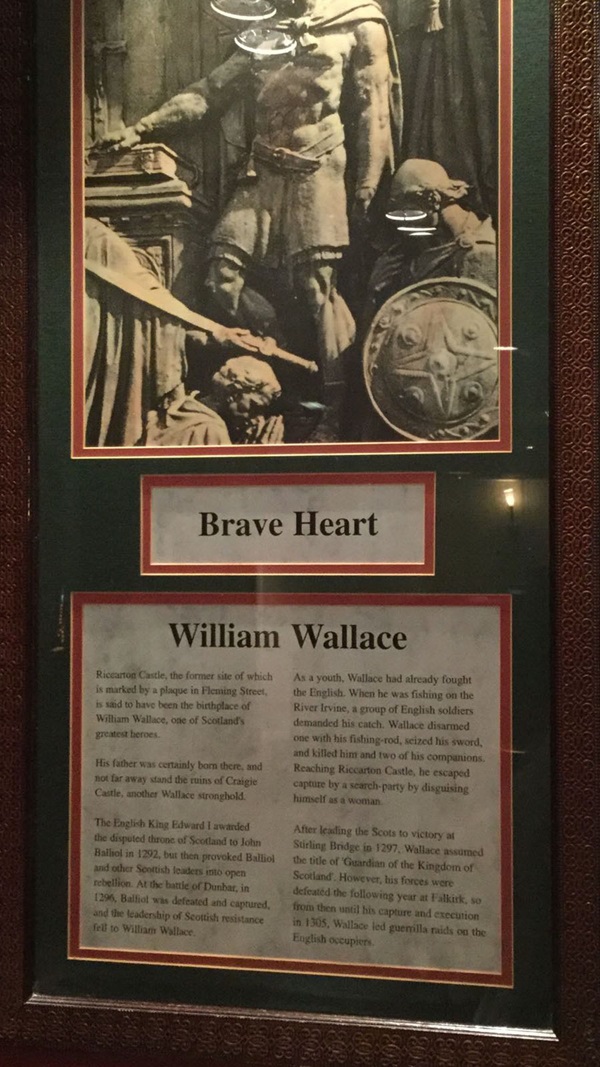

A print and text about William Wallace.

The text reads: Riccarton Castle, the former site of which is marked by a plaque in Fleming Street, is said to have been the birthplace of William Wallace, one of Scotland’s greatest heroes.

His father was certainly born there, and not far away stands the ruins of Craigie Castle, another Wallace stronghold.

The English King Edward I awarded the disputed throne of Scotland to John Balliol in 1292, but then provoked Balliol and other Scottish leaders into open rebellion. At the Battle of Dunbar, in 1296, Balliol was defeated and captured, and the leadership of Scottish resistance fell to William Wallace.

As a youth, Wallace had already fought the English. When he was fighting on the River Irvine, a group of English soldiers demanded his catch. Wallace disarmed one with his fishing rod, seized his sword, and killed him and two of his companions. Reaching Riccarton Castle, he escaped capture by a search party by disguising himself as a woman.

After leading the Scots to victory at Stirling Bridge in 1297, Wallace assumed the title of ‘Guardian of the Kingdom of Scotland’. However, his forces were defeated the following year at Falkirk, so from then until his capture and execution in 1305, Wallace led guerrilla raids on the English occupiers.

Photographs, prints and text about the shoe-making industry.

The text reads: The shoe-making industry was first established in Kilmarnock during the 18th century. AL Clark’s shoe-making company was founded here in 1820, when shoes were still made by hand. A steam powered factory was set up in 1873, and in 1908 the company combined with Abbots to form Saxone Shoes, a name which became world famous. New premises were built on the banks of Kilmarnock Water, and by the 1930s around 1,000 people were employed there. The factory closed in the 1960s after a takeover, and Kilmarnock’s Galleon Centre was opened on the site in 1986.

Top: The old Saxone factory in Titchfield Street

Centre: Saxone tradesmen and apprentices, 1928

Above: Making shoes.

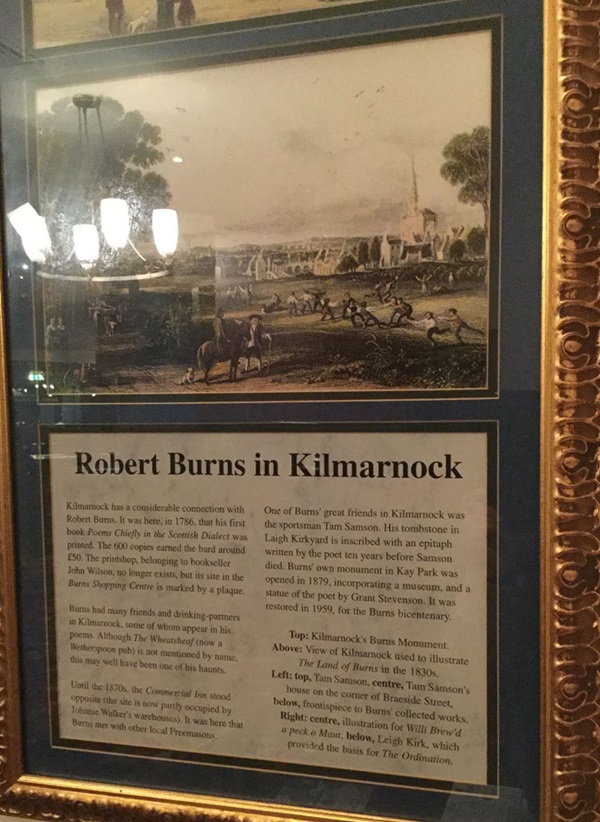

A print and text about Robert Burns in Kilmarnock.

The text reads: Kilmarnock has a considerable connection with Robert Burns. It was here, in 1786, that his first book Poems Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect was printed. The 600 copies earned the bard around £50. The print shop, belonging to bookseller John Wilson, no longer exists but its site in the Burns Shopping Centre is marked by a plaque.

Burns had many friends and drinking partners in Kilmarnock, some of whom appear in his poems. Although The Wheatsheaf (now a Wetherspoon pub) is not mentioned by name, this may well have been one of his haunts.

Until the 1870s, the Commercial Inn stood opposite (the site is now partly occupied by Johnnie Walker’s warehouses). It was here that Burns met with other local Freemasons.

One of Burns’ great friends in Kilmarnock was the sportsman Tam Samson. His tombstone in Laigh Kirkyard is inscribed with an epitaph written by the poet ten years before Samson died. Burns’ own monument in Kay Park was opened in 1879, incorporating a museum, and a statue of the poet by Grant Stevenson. It was restored in 1959, for the Burns bicentenary.

Above: View of Kilmarnock used to illustrate The Land of Burns in the 1830s.

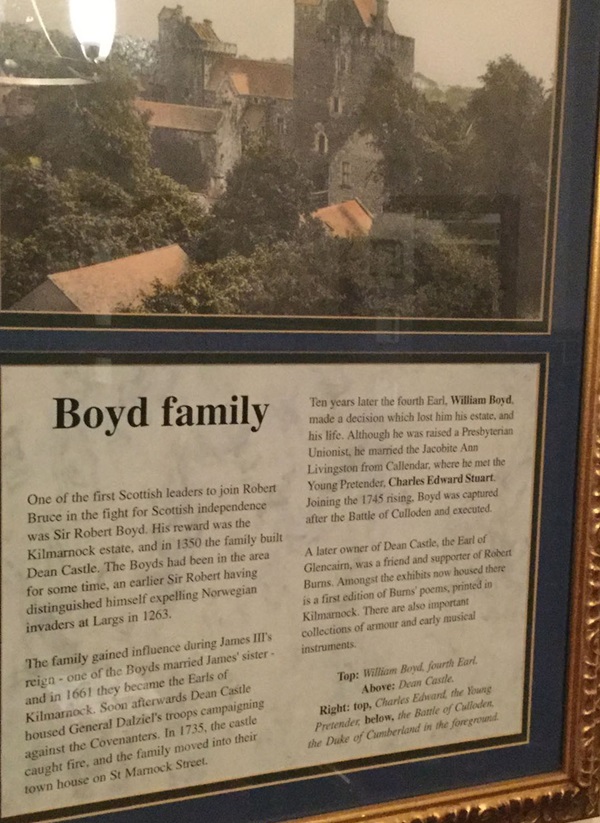

A print and text about the Boyd family.

The text reads: One of the first Scottish leaders to join Robert Bruce in the fight for Scottish independence was Sir Robert Boyd. His reward was the Kilmarnock estate, and in 1350 the family built Dean Castle. The Boyds had been in the area for some time, an earlier Sir Robert having distinguished himself expelling Norwegian invaders at Largs in 1263.

The family gained influence during James III’s reign – one of the Boyds married James’ sister – and in 1661 they became the Earls of Kilmarnock. Soon afterwards Dean Castle housed General Dalziel’s troops campaigning against the Covenanters. In 1735, the castle caught fire, and the family moved into their town house on St Marnock Street.

Ten years later the fourth Earl, William Boyd, made a decision which lost him his estate, and his life. Although he was raised a Presbyterian Unionist, he married the Jacobite Anne Livingston from Callendar, where he met the young pretender, Charles Edward Stuart. Joining the 1745 rising, Boyd was captured after the Battle of Culloden and executed.

A later owner of Dean Castle, the Earl of Glencairn, was a friend and supporter of Robert Burns. Amongst the exhibits now housed there is a first edition of Burns’ poems, printed in Kilmarnock. There are also important collections of armour and early musical instruments.

Above: Dean Castle.

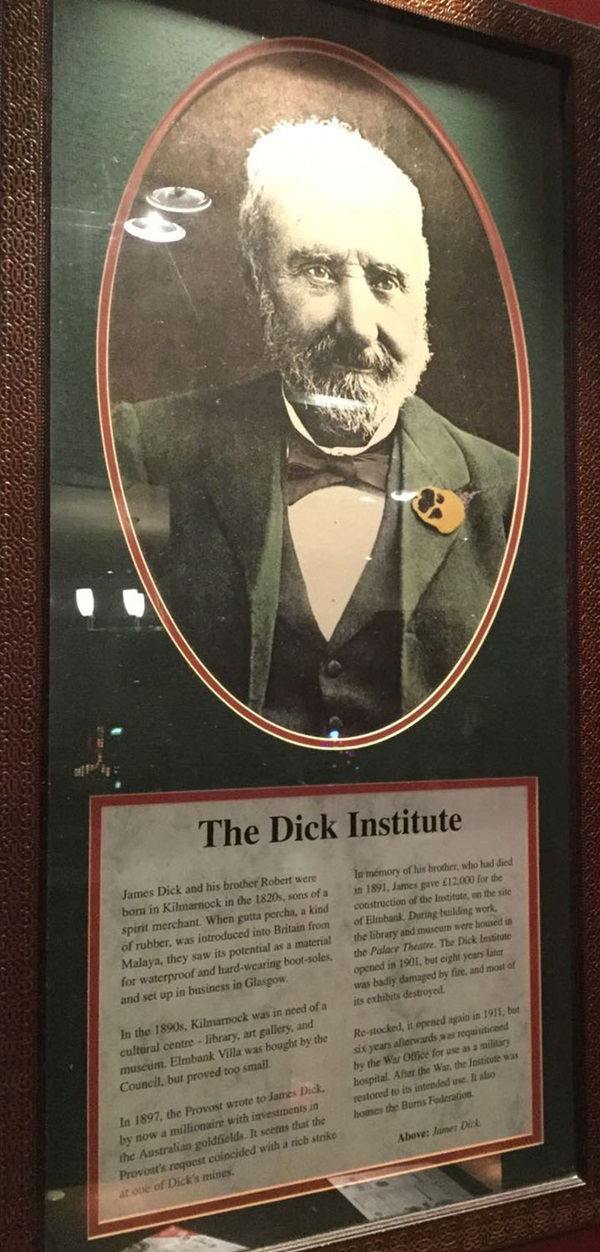

Prints and text about The Dick Institute.

The text reads: James Dick and his brother Robert were born in Kilmarnock in the 1820s, sons of a spirit merchant. When gutta percha, a kind of rubber, was introduced into Britain from Malaya, they saw its potential as a material for waterproof and hard wearing boot soles, and set up business in Glasgow.

In the 1890s, Kilmarnock was in need of a cultural centre – library, art gallery and museum. Elmbank Villa was bought by the council, but proved too small.

In 1897, the provost wrote to James Dick, by now a millionaire with investments in the Australian goldfields. It seems that the provost’s request coincided with a rich strike at one of Dick’s mines.

In memory of his brother, who had died in 1891, James gave £12,000 for the construction of the institute, on the site of Elmbank. During building work, the library and museum were housed in the Palace Theatre. The Dick Institute opened in 1901, but eight years later was badly damaged by fire, and most of its exhibits destroyed.

Re-stocked, it opened again in 1911, but six years afterwards was requisitioned by the War Office for use as a military hospital. After the war, the institute was restored to its intended use. It also houses the Burns Federation.

Above: James Dick.

External photographs of the building – main entrance.