Pub history

The Whalebone

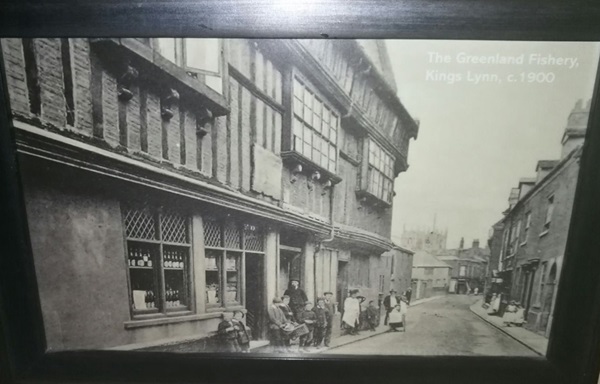

In the early 1700s, nearby King’s Lynn was a flourishing whaling port, fishing the waters off Greenland, with Lynn’s famous Greenland Fishery frequented by whalers. This property’s sales particulars stated that the premises ‘have been occupied as such, with full trade upwards of 60 years’ (since c1748). During these years, the inn was called The Whalebone. Perhaps this is why it got its name or possibly from a souvenir whalebone brought back.

58–64 Bridge Street, Downham Market, Norfolk, PE38 9DJ

In the early 1700s, nearby King’s Lynn was a flourishing whaling port, fishing the waters off Greenland, with Lynn’s famous Greenland Fishery frequented by whalers. This property’s sales particulars stated that the premises ‘have been occupied as such, with full trade upwards of 60 years’ (since c1748). During these years, the inn was called The Whalebone. Perhaps this is why it got its name or possibly from a souvenir whalebone brought back.

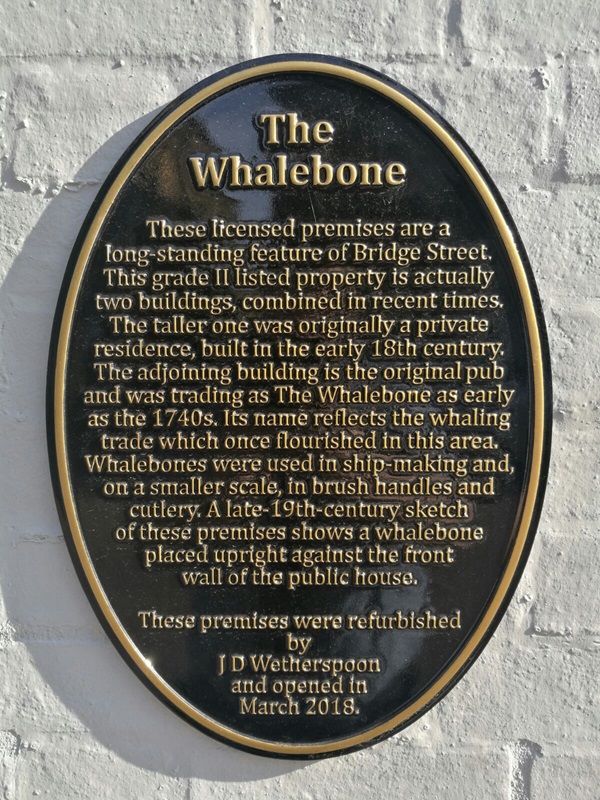

A plaque documenting the history of The Whalebone.

The plaque reads: These licensed premises are a long-standing feature of Bridge Street.

This grade II listed property is actually two buildings, combined in recent times. The taller one was originally a private residence, built in the early 18th century. The adjoining building is the original pub and was trading as The Whalebone as early as the 1740s. Its name reflects the whaling trade which once flourished in this area. Whalebones were used in ship-making and, on a smaller scale, in brush handles and cutlery. A late 19th century sketch of these premises shows whalebone placed upright against the front wall of the public house.

These premises were refurbished by J D Wetherspoon and opened in March 2018

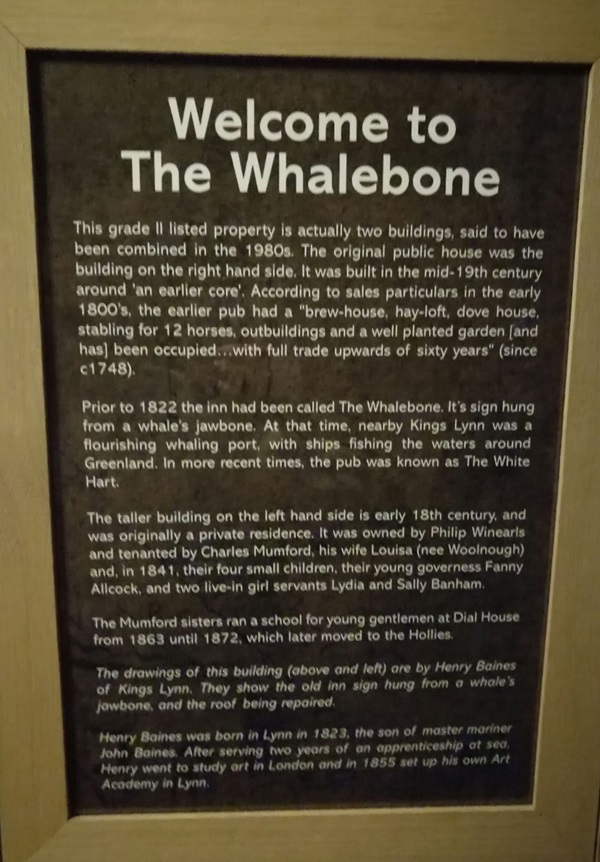

Text about The Whalebone.

The text reads: This grade II listed property is actually two buildings, said to have been combined in the 1980s. The original public house was the building on the right hand side. It was built in the mid 19th century around ‘an earlier core’. According to sales particulars in the early 1800s, the earlier pub had a “brew-house, hay-loft, dove house, stabling for 12 horses, outbuildings and a well planted garden [and has] been occupied…with full trade upwards of sixty years” (since c1748).

Prior to 1822 the inn had been called The Whalebone. Its sign hung from a whale’s jawbone. At the time, nearby King’s Lynn was a flourishing whaling port, with ships fishing the waters around Greenland. In more recent times, the pub was known as The White Hart.

The taller building on the left hand side is early 18th century, and was originally a private residence. It was owned by Philip Winearls and tenanted by Charles Mumford, their young governess Fanny Allcock, and two live-in girl servants Lydia and Sally Banham.

The Mumford sisters ran a school for young gentlemen at Dial House from 1863 until 1872, which later moved to Hollies.

The drawings of this building are by Henry Baines of King’s Lynn. They show the old inn sign hung from the whale’s jawbone, and the roof being repaired.

Henry Baines was born in Lynn in 1823, the son of master mariner John Baines. After serving two years of an apprenticeship at sea, Henry went to study art in London and in 1855 set up his own Art Academy in Lynn.

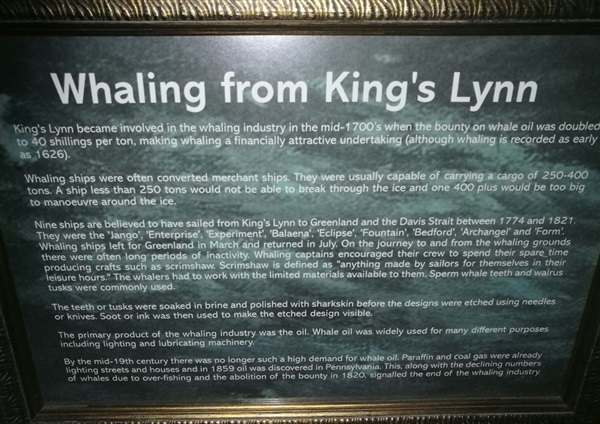

Text about whaling from King’s Lynn.

The text reads: King’s Lynn became involved in the whaling industry in the mid 1700s when the bounty on whale oil was doubled to 40 shillings per ton, making whaling a financially attractive undertaking (although whaling is recorded as early as 1626).

Whaling ships were often converted merchant ships. They were usually capable of carrying cargo of 250-400 tons. A ship less than 250 tons would not be able to break through the ice and one 400 plus would be too big to manoeuvre around the ice.

Nine ships are believed to have sailed from King’s Lynn to Greenland and the Davis Strait between 1774 and 1821. They were the Jango, Experiment, Balaena, Eclipse, Fountain, Bedford, Archangel and Form. Whaling ships left for Greenland in March and returned in July. On the journey to and from the whaling grounds there were often long periods of inactivity. Whaling captains encouraged their crew to spend their spare time producing crafts such as scrimshaw. Scrimshaw is defined as “anything made by sailors for themselves in their leisure hours”. The whalers had to work with the limited materials available to them. Sperm whale teeth and walrus tusks were commonly used.

The teeth or tusks were soaked in brine and polished with sharkskin before the designs were etched using needles or knives. Soot or ink was then used to make the etch design visible.

The primary product of the whaling industry was the oil. Whale oil was widely used for many different purposes including lighting and lubricating machinery.

By the mid 19th century there was no longer such high demand for whale oil. Paraffin and coal gas were already lighting streets and houses and in 1859 oil was discovered in Pennsylvania. This, along with the declining numbers of whales due to over-fishing and the abolition in 1820, signalled the end of the whale industry.

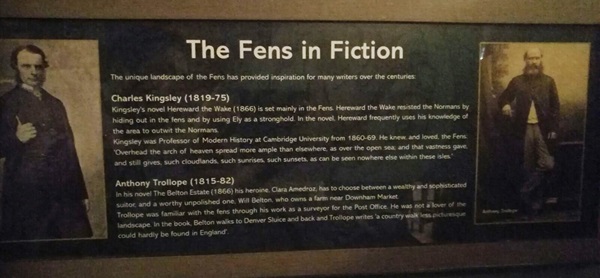

Prints and text about the Fens.

The text reads: The unique landscape of the Fens has provided inspiration for many writers over the centuries:

Charles Kingsley (1819-75)

Kingsley’s novel Hereward the Wake (1866) is set mainly in the Fens. Hereward the Wake resisted the Normans by hiding out in the fens and by using Ely as a stronghold. In the novel, Hereford frequently uses his knowledge of the area to outwit the Normans.

Kingsley was a professor of modern history at Cambridge University from 1860-69. He knew, and loved, the Fens: “Overhead the arch of heaven spread more ample than elsewhere, as over the open sea; and that vastness gave, and still gives, such cloudlands, such sunsets, as can be seen nowhere else within these isles”.

Antony Trollope (1815-82)

In his novel The Belton Estate (1866) his heroine, Ciara Amedroz, has to choose between a wealthy and sophisticated suitor, and a worthy unpolished one, Will Belton, who owns a farm near Downham Market.

Trollope was familiar with the fens through his work as a surveyor for the post office. He was not a lover of the landscape. In the book, Belton walks to Denver Sluice and back Trollope writes “a country walk less picturesque could hardly be found in England”.

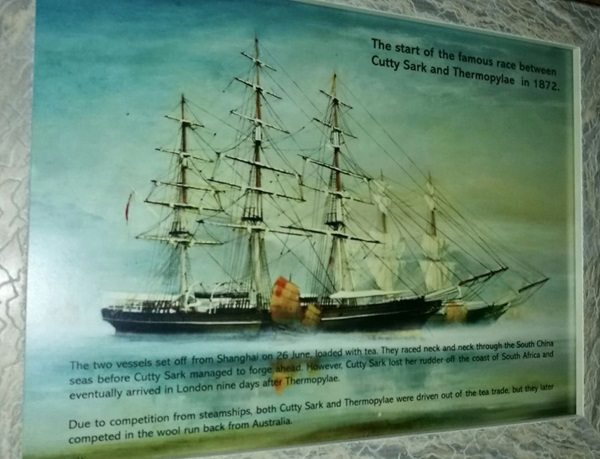

An illustration and text about the famous race between Cutty Sark and Thermopylae in 1872.

The text reads: The two vessels set off from Shanghai on 26 June, loaded with tea. They raced neck and neck through the South China seas before Cutty Sark managed to forge ahead. However, Cutty Sark lost her rudder off the coast of South Africa and eventually arrived in London nine days after Thermopylae.

Due to competition from steamships, both Cutty Sark and Thermopylae were driven out of the tea trade, but they later competed in the wool run back from Australia.

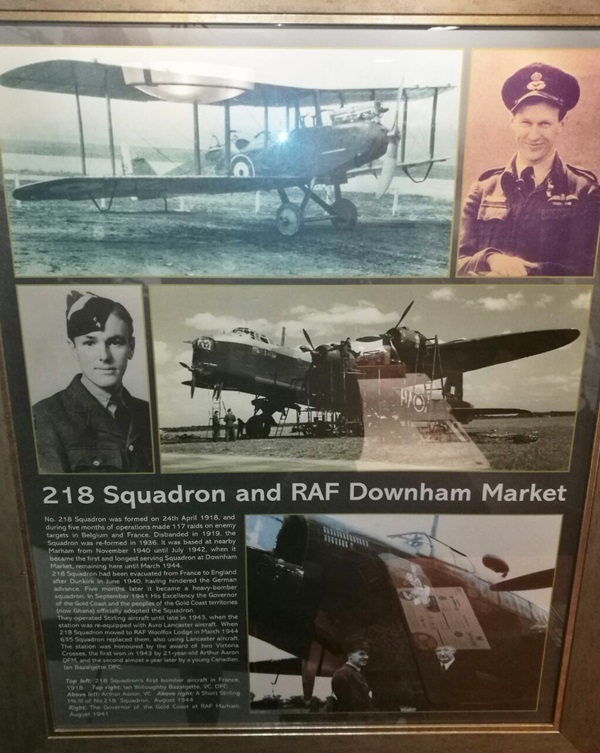

Photographs and text about 218 Squadron and RAF Downham Market.

The text reads: No. 218 Squadron was formed on 24 April 1918, and during five months of operations made 117 raids on enemy targets in Belgium and France. Disbanded in 1919, the Squadron was re-formed in 1936. It was based at nearby Marham from November 1940 until July 1942, when it became the first and longest serving Squadron at Downham market, remaining here until March 1944.

218 Squadron had been evacuated from France to England after Dunkirk in June 1940, having hindered the German advance. Five months later it became a heavy bomber squadron. In September 1941 His Excellency the Governor of the Gold Coast and the people of the Gold Coast territories (now Ghana) officially adopted the Squadron.

They operated Stirling aircraft until late 1943, when the station was re-equipped with Avro Lancaster aircraft. When 218 Squadron moved to RAF Woolfox Lodge in March 1944. 635 Squadron replaced them, also using Lancaster aircraft. The station was honoured by the award of two Victoria Crosses, the first won in 1943 by 21 year old Arthur Aaron DFM, and the second almost a year later by a young Canadian Ian Bazalgette DFC.

Top left: 218 Squadron’s first bomber aircraft in France, 1918

Top right: Ian Willoughby Bazalgette, VC, DFC

Above left: Arthur Aaron, VC

Right: The Governor of the Gold Coast at RAF Marham, August 1941.

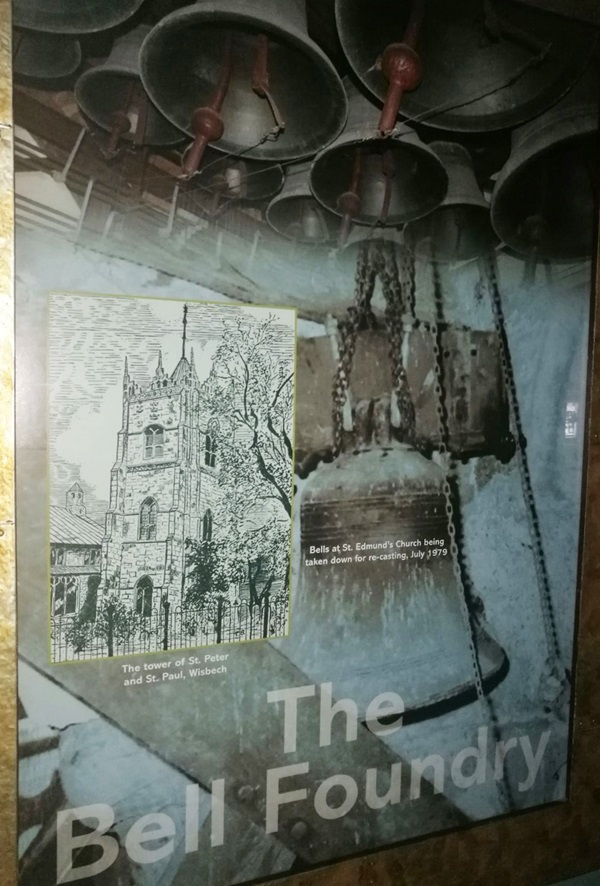

A photograph of the bells at St Edmund’s Church being taken down for re-casting, July 1979.

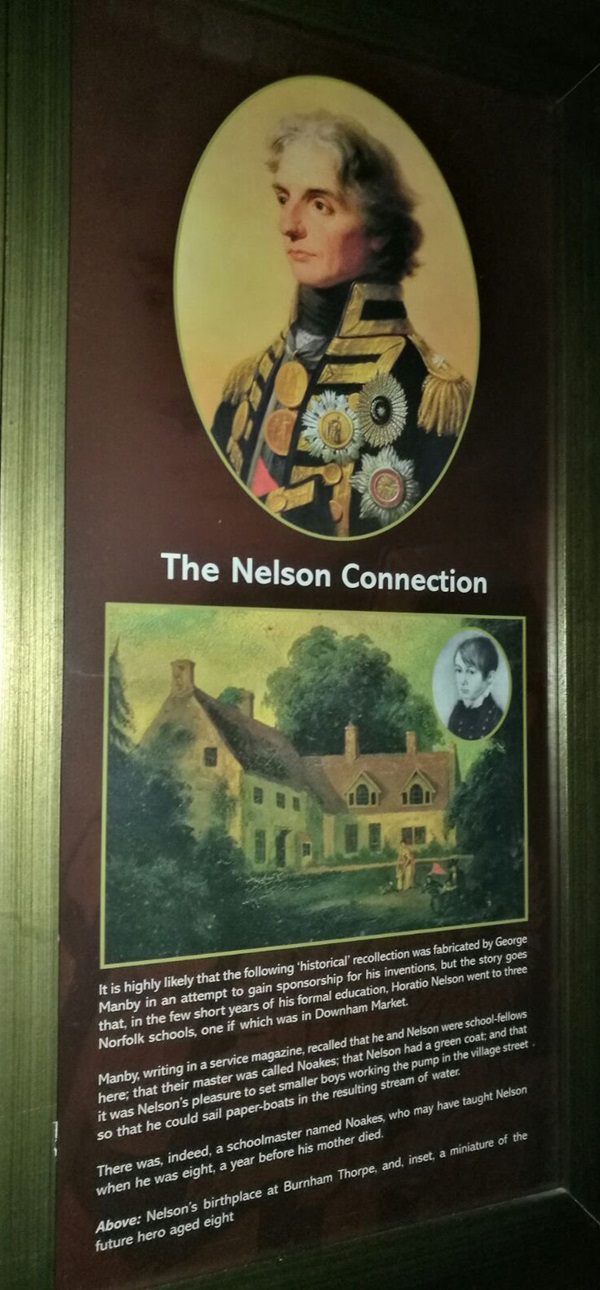

Illustrations and text about the Nelson connection.

The text reads: It is likely that the following ‘historical’ recollection was fabricated by George Manby in an attempt to gain sponsorship for his inventions, but the story goes that, in the few short years of his formal education, Horatio Nelson went to three Norfolk schools, one of which was in Downham Market.

Manby, writing in a service magazine, recalled that he and Nelson were school fellows here; that their master was called Noakes; that Nelson had a green coat; and that it was Nelson’s pleasure to set smaller boys working the pump in the village street so that he could sail paper boats in the resulting stream of water.

There was, indeed, a schoolmaster named Noakes, who may have taught Nelson when he was eight, a year before is mother died.

Above: Nelson’s birthplace at Burnham Thorpe, and, inset, a miniature of the future hero aged eight.

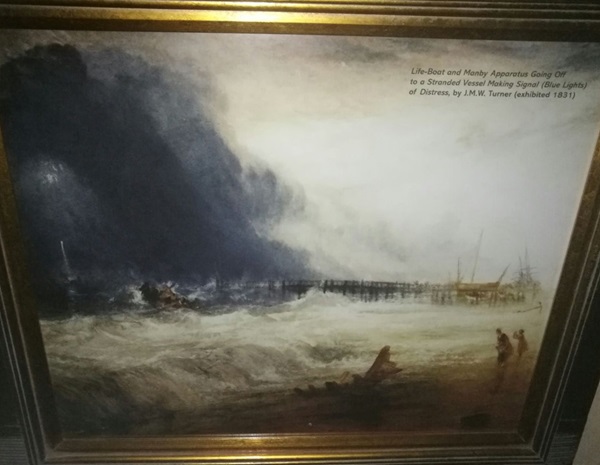

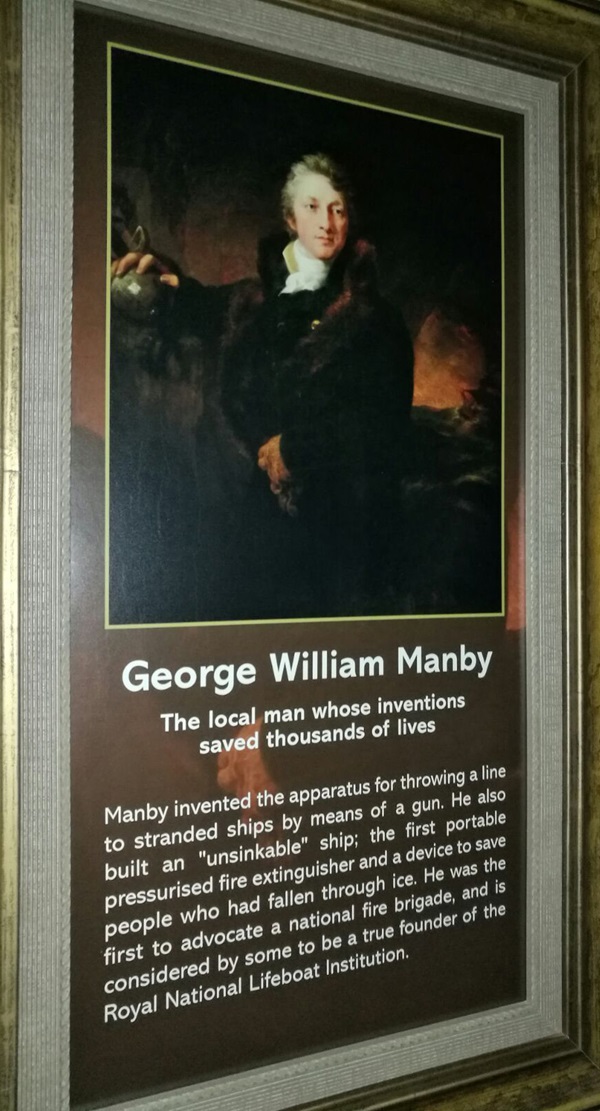

A print and text about George William Manby.

The text reads: Manby invented the apparatus for throwing a line to stranded ships by means of gun. He also built an “unsinkable” ship; the first portable pressurised fire extinguisher and a device to save people who had fallen through ice. He was the first to advocate a national fire brigade, and is considered by some to be a true founder of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution.

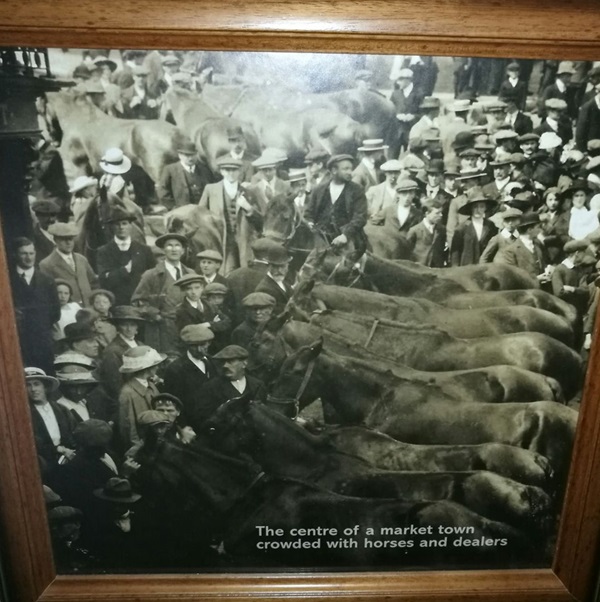

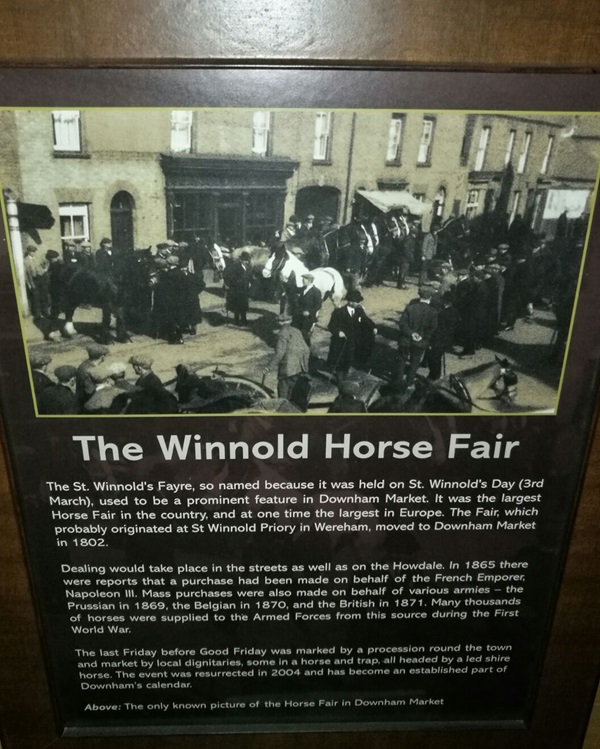

A photograph and text about the Winnold Horse Fair.

The text reads: The St Winnold’s Fayre, so named because it was held on St Winnold’s Day (3 March), used to be a prominent feature in Downham Market. It was the largest horse fair in the country, and at one time the largest in Europe. The fair, which probably originated at St Winnold Priory in Wareham, moved to Downham Market in 1802.

Dealing would take place in the streets as well as on the Howdale. In 1864 there were reports that a purchase had been made on behalf of the French Emperor, Napoleon III. Mass purchases had been made on behalf of various armies – the Prussian in 1869, the Belgian in 1870, and the British in 1871. Many thousands of horses were supplied to the Armed Forces from this source during the First World War.

The last Friday before Good Friday was marked by a procession round the town and market by local dignitaries, some in a horse and trap, all headed by a led shire horse. The event was resurrected in 2004 and has become an established part of Downham’s calendar.

Above: The only known picture of the horse fair in Downham Market.

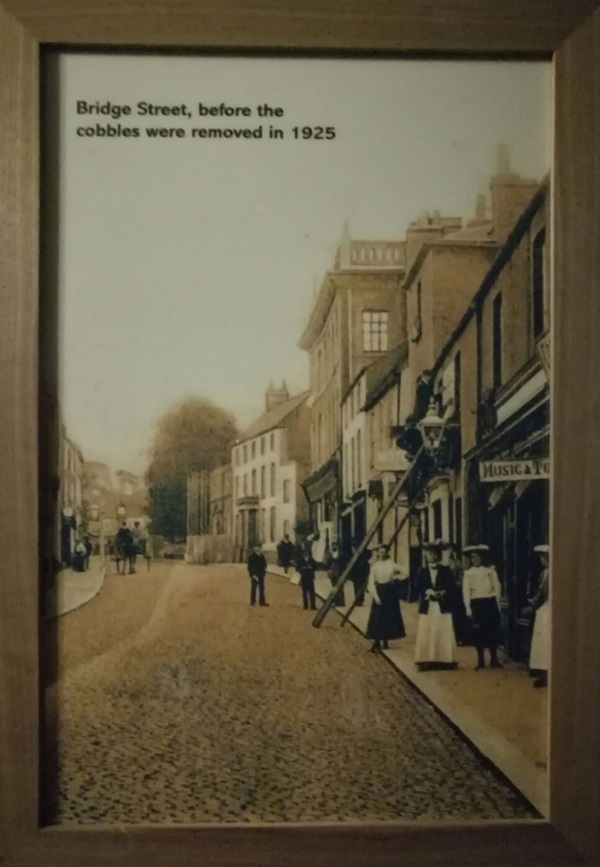

A photograph of Bridge Street, before the cobbles were removed in 1925.

Old photographs of Bridge Street.

Top photo: Bridge Street with the Quaker Meeting House on the right

Bottom photo: A similar view to the one above, around 25 years later.

A painting entitled Life-Boat and Mandy Apparatus Going Off to a Stranded Vessel Making Signal (Blue Lights) of Distress, by JMW Turner.

A photograph of the centre of a market town crowded with horses and dealers.

A photograph of the Greenland Fishery, King’s Lynn, c1900.

Whalebone replicas are on display throughout the pub.

An early whale oil lamp, c1795.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.