Pub history

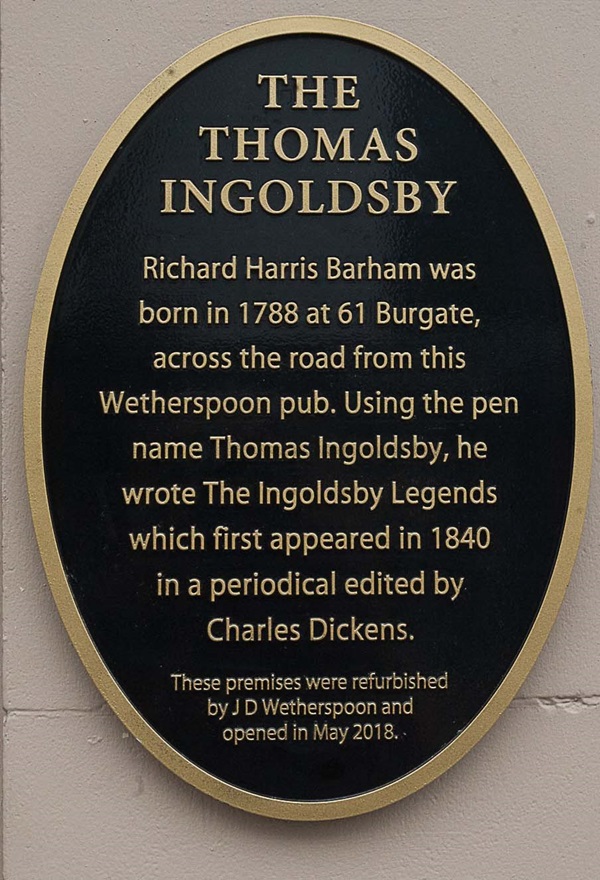

The Thomas Ingoldsby

Richard Harris Barham was born in 1788, at 61 Burgate, across the road from this Wetherspoon pub. Using the pen name Thomas Ingoldsby, he wrote The Ingoldsby Legends which first appeared in 1840, in a periodical edited by Charles Dickens.

5–9 Burgate, Canterbury, Kent, CT1 2HG

Richard Harris Barham was born in 1788, at 61 Burgate, across the road from this Wetherspoon pub. Using the pen name Thomas Ingoldsby, he wrote The Ingoldsby Legends which first appeared in 1840, in a periodical edited by Charles Dickens.

A plaque documenting the history of The Thomas Ingoldsby.

The plaque reads: Richard Harris Bahram was born in 1788 at 61 Burgate across the road from this Weatherspoon pub. Using the pen name Thomas Ingoldsby, he wrote The Ingoldsby Legends which first appeared in 1840 in a periodical edited by Charles Dickens.

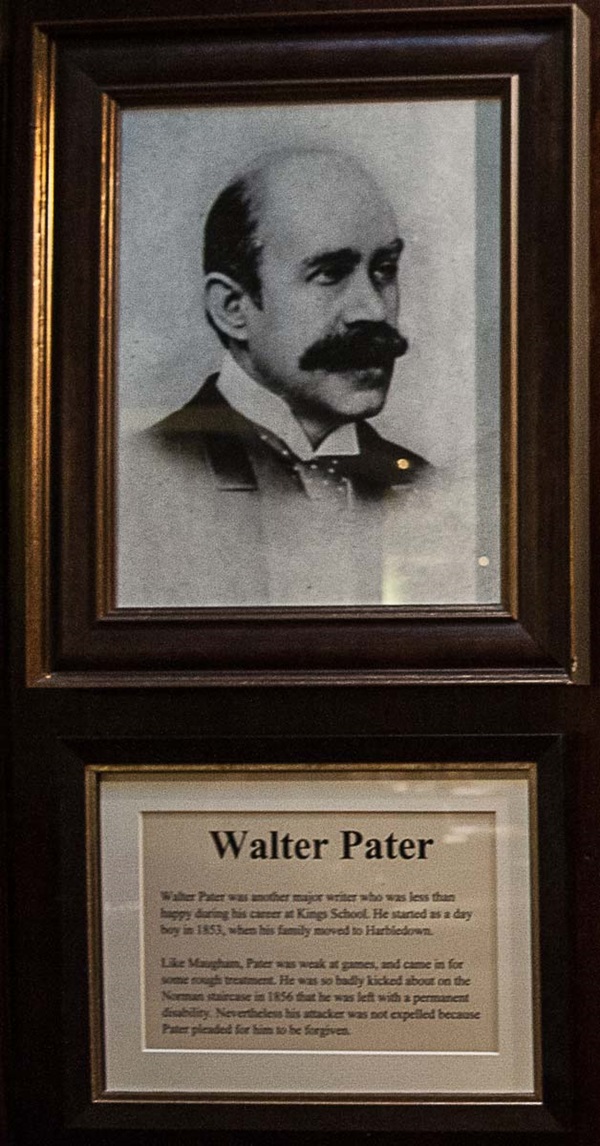

A photograph and text about Walter Pater.

The text reads: Walter pater was another major writer who was less than happy during his career at Kings School. He started as a day boy in 1853, when his family moved to Harbledown.

Like Mangham, Pater was weak at games, and came in for some rough treatment. He was so badly kicked about on the Norman staircase on 1856 that he was left in permanent disability. Nevertheless his attacker was not expelled because Pater pleaded for him to be forgiven.

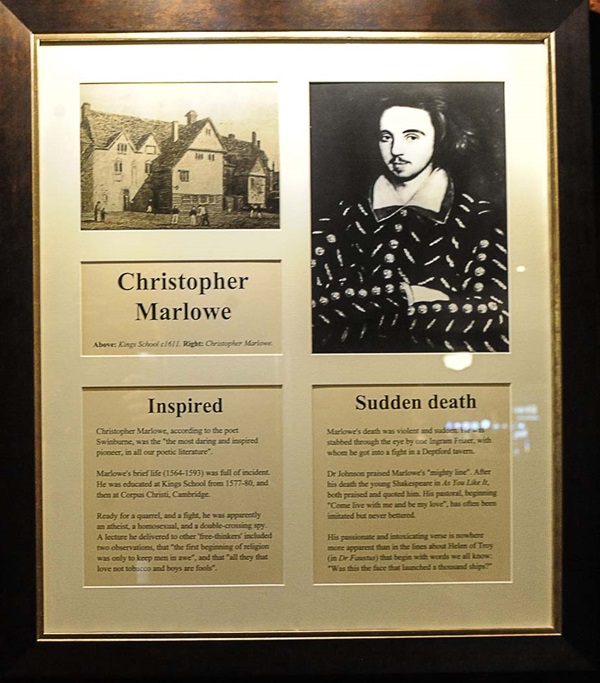

Prints and text about Christopher Marlowe.

The text reads: Christopher Marlowe, according to the poet Swinburne, was “the most darling and inspired pioneer, in all our poetic literature.”

Marlowe’s brief life (1564-93) was full of incident. He educated at Kings School from 1577-80, and then at Corpus Christi, Cambridge.

Ready for a quarrel and a fight, he was apparently an atheist, a homosexual and a double-crossing spy. A lecture he delivered to other “free-thinkers” included two observations that “the first beginning of religion was only to keep men in awe”, and that “all they that love not tobacco and boys are fools”.

Marlowe’s death was violent and sudden. He was stabbed through the eye by Ingram Frizer, with whom he got into a fight in a Deptford tavern.

Dr. Johnson praised Marlowe’s “mighty line”. After his death the young Shakespeare in As You Like It, both praised and quoted him. His pastoral, beginning “come live with me and be my love” has often been imitated but never bettered.

His passionate and intoxicating verse is nowhere more apparent than in the lines about Helen of Troy (in Dr Fantasia) that begin with words we all know: “was this the face that launched a thousand ships?”

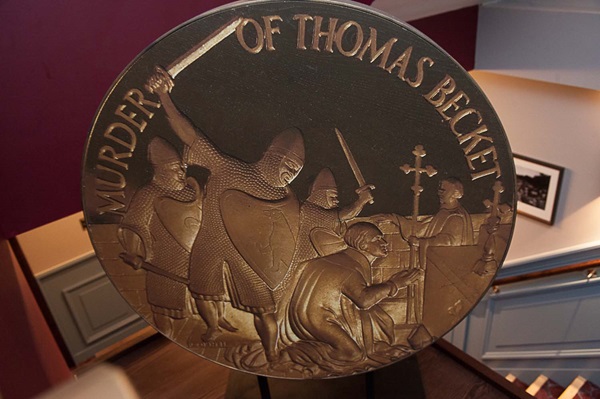

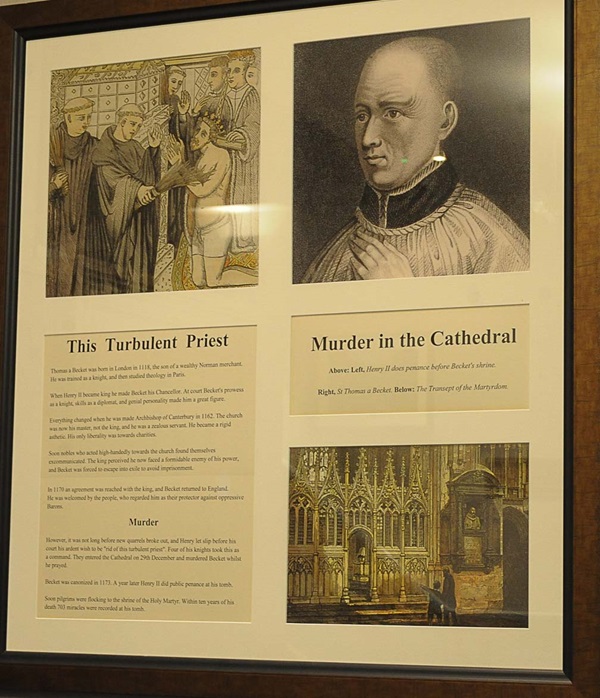

Illustrations and text about a murder in the cathedral.

The text reads: Thomas a Becket was born in London 1118, the son of a wealthy Norman merchant. He was trained as a knight, then studied theology in Paris.

When Henry II became king he made Becket his chancellor. At court Beckets progress as a knight, skills as a diplomat, and genial personality made him a great figure.

Everything changed when he was made Archbishop of Canterbury in 1162. The church was now his master, not the king and he was a zealous servant, He became a rigid aesthetic. His only liberality was towards charities.

Soon nobles who acted high-handley towards the church found themselves excommunicated. The King perceived he now faced a formidable enemy of his power, and Becket was forced to escape into exile to avoid imprisonment.

In 1170 an agreement was reached with the King, and Becket returned to England. He was welcomed by the people, who regarded him as their protector against oppressive Barons.

However it was not long before new quarrels broke out, and Henry let slip before his court his ardent wish to be “rid if this turbulent priest”. Four of his knights took this as a command. They entered the cathedral on 29 December and murdered Becket whilst he prayed.

Becket was canonized in 1173. A year later Henry II did public penance at his tomb.

Soon pilgrims were flocking to the shrine of the Holy Martyr. Within ten years of his death 703 miracles were recorded at his tomb.

A plaque illustrating Thomas Becket’s murder.

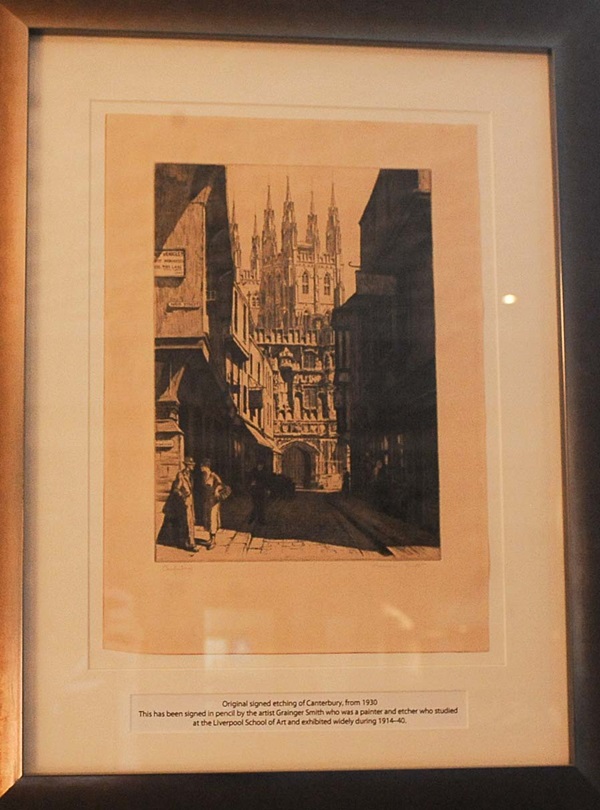

An original signed etching of Canterbury, from 1930.

This has been signed in pencil by the artist Grainger Smith who was a painter and etcher who studies at the Liverpool school of art and exhibited widely during 1914-40.

A photograph and text about west gate, cathedral, 1890.

The text reads: This medieval gatehouse, within the city wall, is the largest-surviving city gate in England. Built of Kentish rag stone around 1379 by Archbishop Sudbury, it is the last survivor of Canterbury’s seven medieval gates.

A photograph of Cathedral Gardens, c1868.

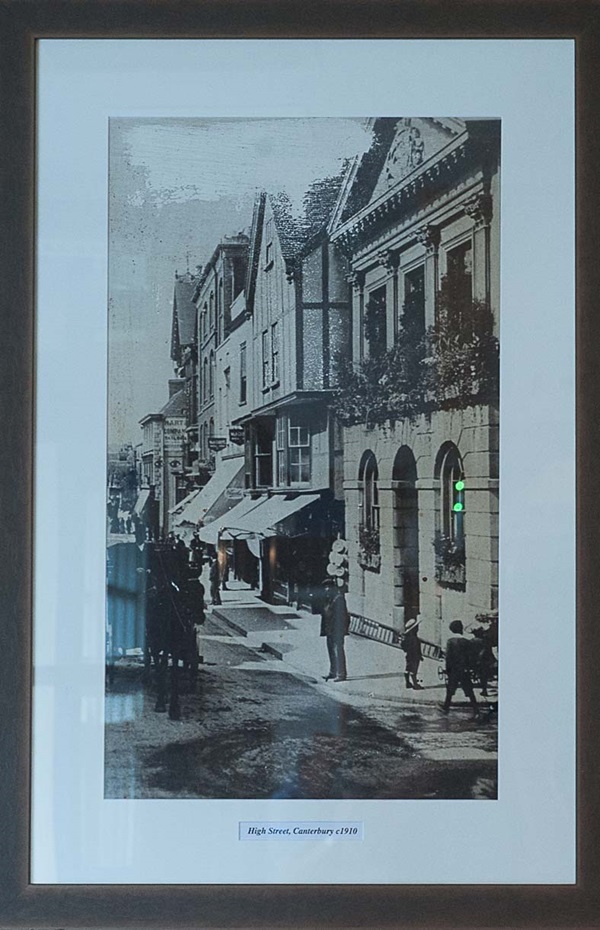

A photograph of High Street, Canterbury, c1910.

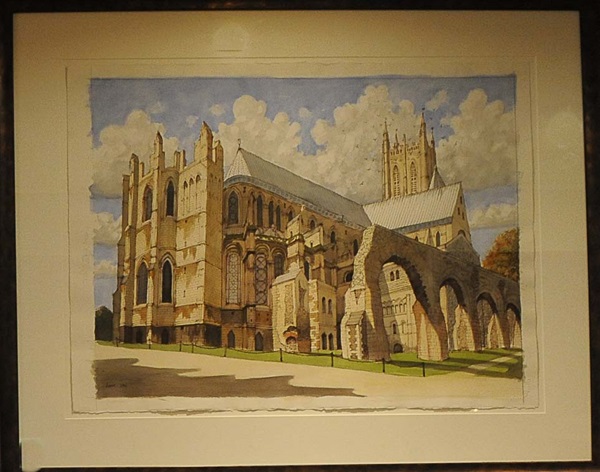

A painting of Canterbury Cathedral.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.