Pub history

The Tailor’s Chalk

Numbers 47 and 49 High Street were originally two long-standing shops – part of a parade built in late Victorian times. From c1900 until World War II, no.47 was Eastman’s drying and cleaning business. For many years, no.49 was occupied by a succession of high-class tailors. It was here that a tailor’s chalk was used to mark seams, showing where fabric needed to be cut or garments altered.

47–49 Sidcup High Street, Sidcup, London, DA14 6ED

Numbers 47 and 49 High Street were originally two long-standing shops – part of a parade built in late Victorian times. From c1900 until World War II, no.47 was Eastman’s drying and cleaning business. For many years, no.49 was occupied by a succession of high-class tailors. It was here that a tailor’s chalk was used to mark seams, showing where fabric needed to be cut or garments altered.

Text about The Tailor’s Chalk.

The text reads: These premises are two former shops (47 and 49 High Street). They were part of a parade built in late Victorian times. In 1903, no.49 was occupied by Merton’s, the tailor. During the 1930s, the “high class tailor” was W J Cooper, who also used a tailor’s chalk to mark seams and cutting lines. The property was remoulded by J D Wetherspoon in April 2009.

Tailor’s chalk is used to make markings on cloth where fabric needs to be cut or to indicate darting lines on garments as they are to be constructed. It is also used when garments need to be altered. Tailors chalk is quick and easy to use, and can be brushed off, leaving no trace behind. It helps, when fitting a suit, to mark fabric rather than make the customer stand still while the fabric is pinned. Classically, tailors chalk is a thin wedge, with the edge used to apply chalk to the fabric.

The name tailor chalk is misleading, however. It isn’t actually chalk at all: it’s usually made from talc.

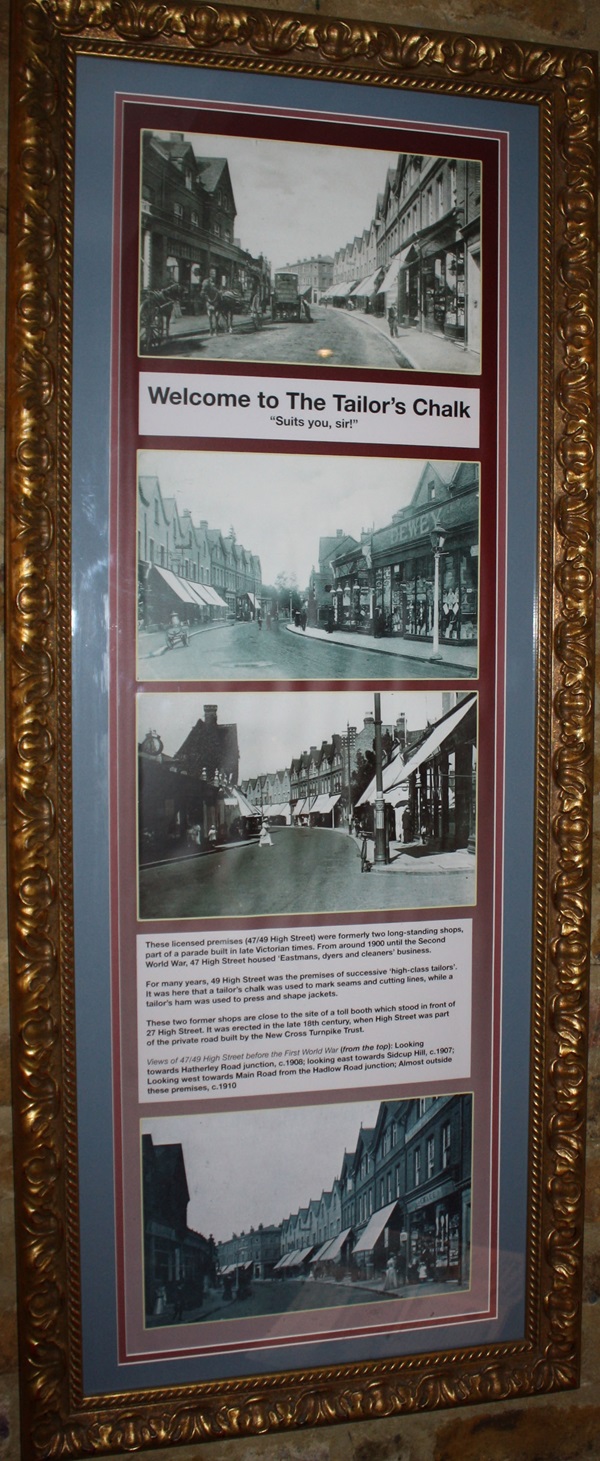

Photographs and text about The Tailor’s Chalk.

The text reads: These licensed premises (47/49 High Street) were formerly two- long standing shops, part of a parade built in late Victorian times. From around 1900 until the Second World War, 47 High Street housed ‘Eastman’s, dryer and cleaner business’.

For many years, 49 High Street was the premises of successive ‘high class tailors’. It was here that tailors chalk was used to mark seams and cutting lines, while a tailor’s ham was used to press and shape jackets.

These two former shops are close to the site of a toll booth which stood in front of 27 High Street. It was erected in the late 18th century, when High Street was part of the private road built by the New Cross Turnpike Trust.

Views of 47/49 High Street before the First World War (from the top): Looking towards Hatherley Road Junction, c1908; looking east towards Sidcup Hill, c1907; looking west towards Main Road from the Hadlow Road junction; almost outside these premises, c1910.

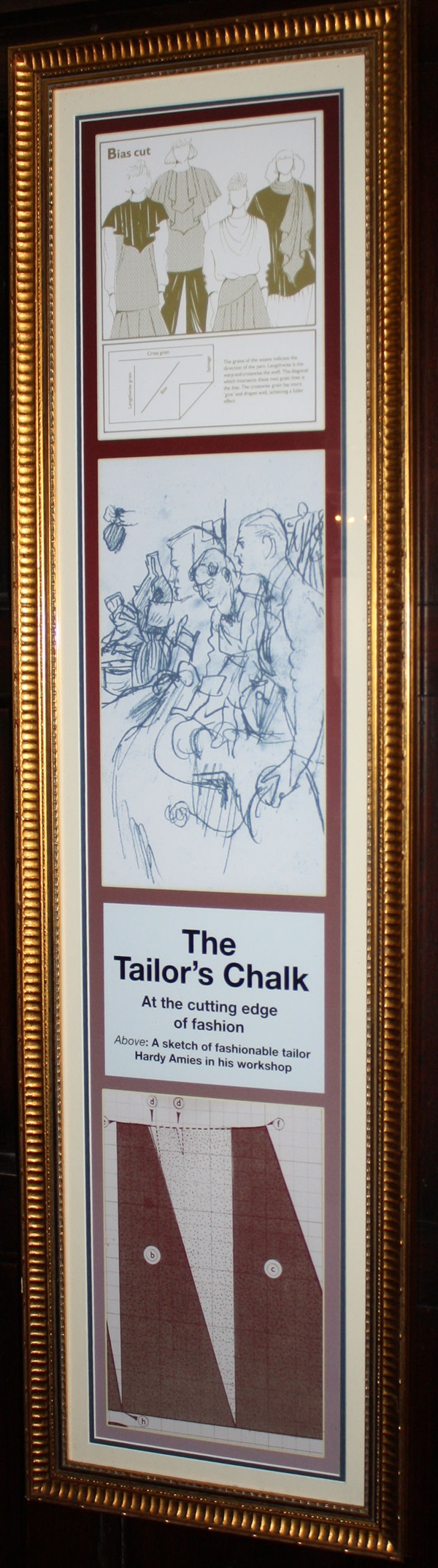

A sketch of fashionable tailor Hardy Amies in his workshop.

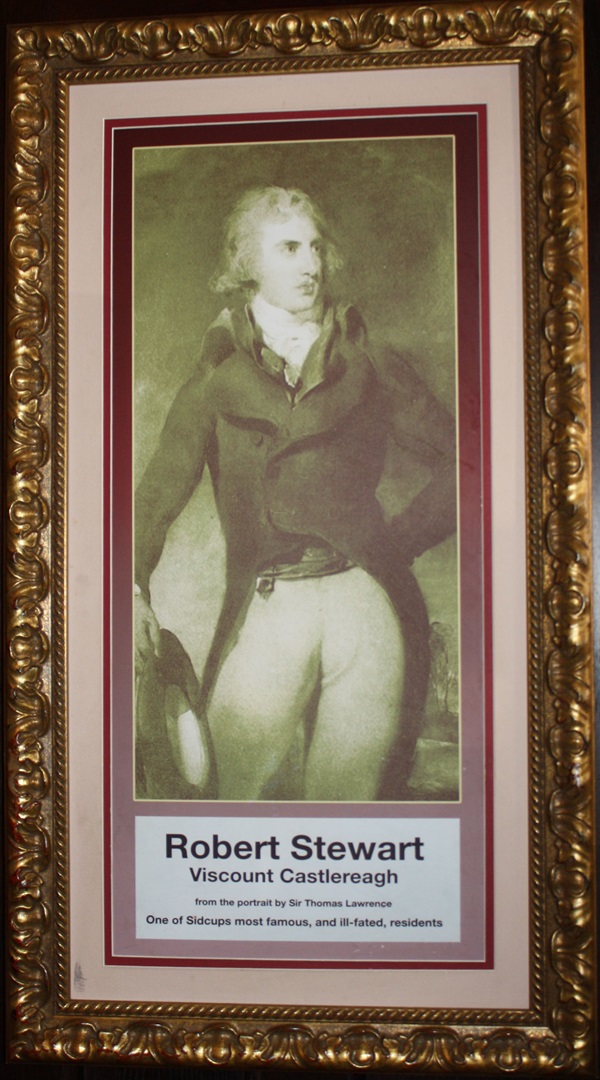

A portrait of Robert Stewart by Sir Thomas Lawrence.

One of Sidcup’s most famous, and ill-fated, residents.

Photographs and text about ‘Sette Copp’.

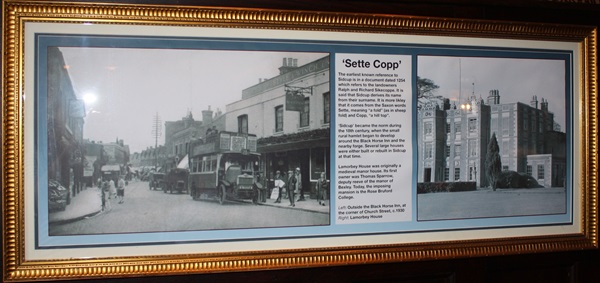

The text reads: The earliest known reference to Sidcup is in a document dated 1254 which refers to the landowners Ralph and Richard Sikecoppe. It is said that Sidcup derives its name from their surname. It is more likely that it comes from the Saxon words Sette, meaning “a fold” (as in sheep fold) and Copp, “a hill top”.

‘Sidcup’ became the norm during the 18th century, when the small rural hamlet began to develop around the Black Horse Inn and the nearby forge. Several large houses were either built or rebuilt in Sidcup at that time.

Lamorbey House was originally a medieval manor house. Its first owner was Thomas Sparrow, deputy reeve of the manor of Bexley. Today, the imposing mansion is the Rose Bruford College.

Left: Outside the Black Horse Inn, at the corner of Church Street, c1930

Right: Lamorbey House.

A photograph and text about the railway in Sidcup.

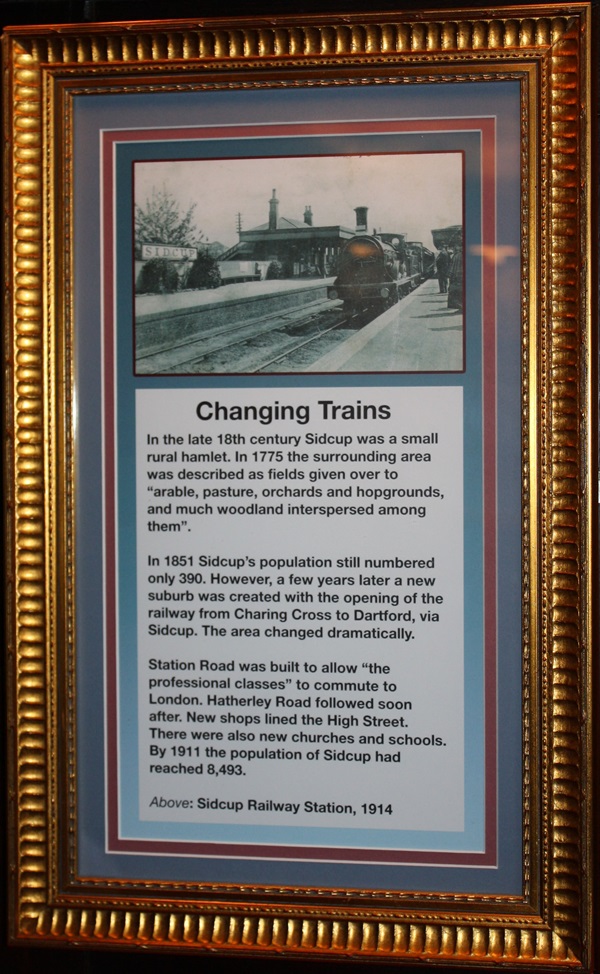

The text reads: In the late 18th century Sidcup was a small rural hamlet. In 1775 the surrounding area was described as fields given over to “arable, pasture, orchards and hopgrounds, and much woodland interspersed among them.

In 1851 Sidcup’s population still numbered only 390. However, a few years later a new suburb was created with the opening of the railway from Charing Cross to Dartford, via Sidcup. The area changed dramatically.

Station Road was built to allow “the professional classes” to commute to London. Hatherley Road followed soon after. New shops lined the High Street. There were also new churches and schools. By 1911 the population of Sidcup had reached 8,493.

Above: Sidcup Railway Station, 1914.

Prints and text about Frognal House and the Lords Sydney.

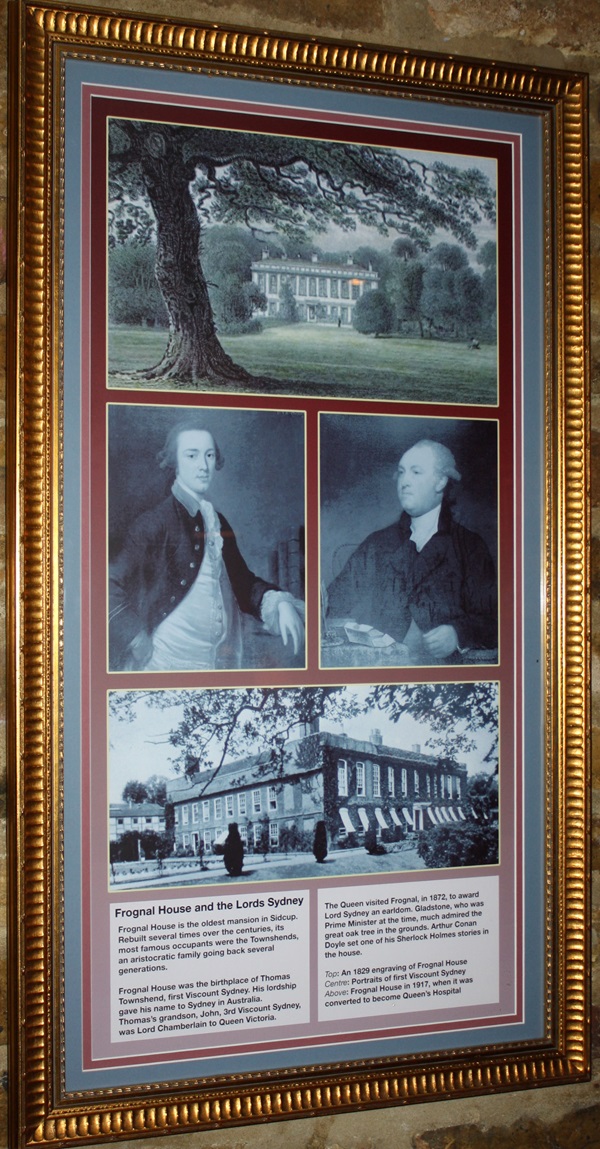

The text reads: Frognal House is the oldest mansion in Sidcup. Rebuilt several times over the centuries, its most famous occupants were the Townshends, an aristocratic family going back several generations.

Frognal House was the birthplace of Thomas Townshend, first viscount Sydney. His lordship gave his name to Sydney in Australia. Thomas’s grandson, John, third Viscount Sydney, was Lord Chamberlain to Queen Victoria.

The Queen visited Frognal, in 1872, to award Lord Sydney an earldom. Gladstone, who was Prime Minister at the time, much admired the great oak tree in the grounds. Arthur Conan Doyle set one of his Sherlock Holmes stories in the house.

Top: An 1829 engraving of Frognal House

Centre: Portraits of first Viscount Sydney

Above: Frognal House in 1917, when it was converted to become Queen’s Hospital.

Photographs and text about Queens Hospital.

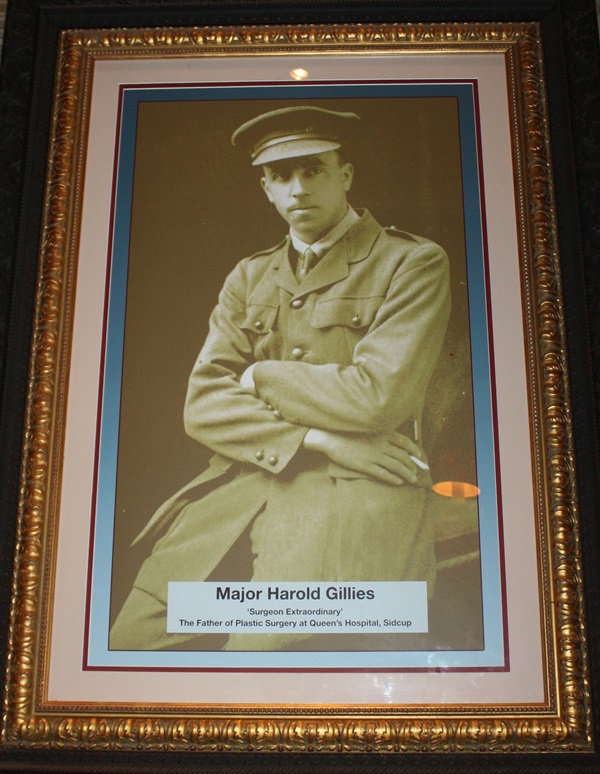

The text reads: Towards the end of the First World War, a collection of huts were set up in the grounds of Frognal House. Called the Queen’s Hospital, it treated servicemen with injuries to the face and jaw.

Queen’s opened in June 1917, with over 1,000 beds. Led by Major Harold Gillies, the team of doctors performed more than 11,000 operations on 5,000 patients. The hospital became internationally known for its facial plastic surgery.

In 1930 it was renamed Queen Mary’s and became a general hospital. Gillies was knighted the same year. New Zealand born and later London based, Sir Harold Gillies is widely regarded as the father of plastic surgery.

Above: Harold Gillies in 1915, a medical officer working with the Red Cross

Top left: Sir Harold Gillies, C.B.E., F.R.C.S.

Bottom left: The operating theatre at Queen’s Hospital, where Gillies carried out his pioneering work

Top centre: Sketch of Gillies during an operation

Left: Gillies, standing third from left, during Queen Alexandra’s visit to Queen’s Hospital in 1917.

A photograph of Major Harold Gillies – the father of plastic surgery at Queens Hospital.

A photograph of Ethel Smyth.

The renowned suffragette and composer, born in Sidcup in 1858, with her dog Marco, in 1891.

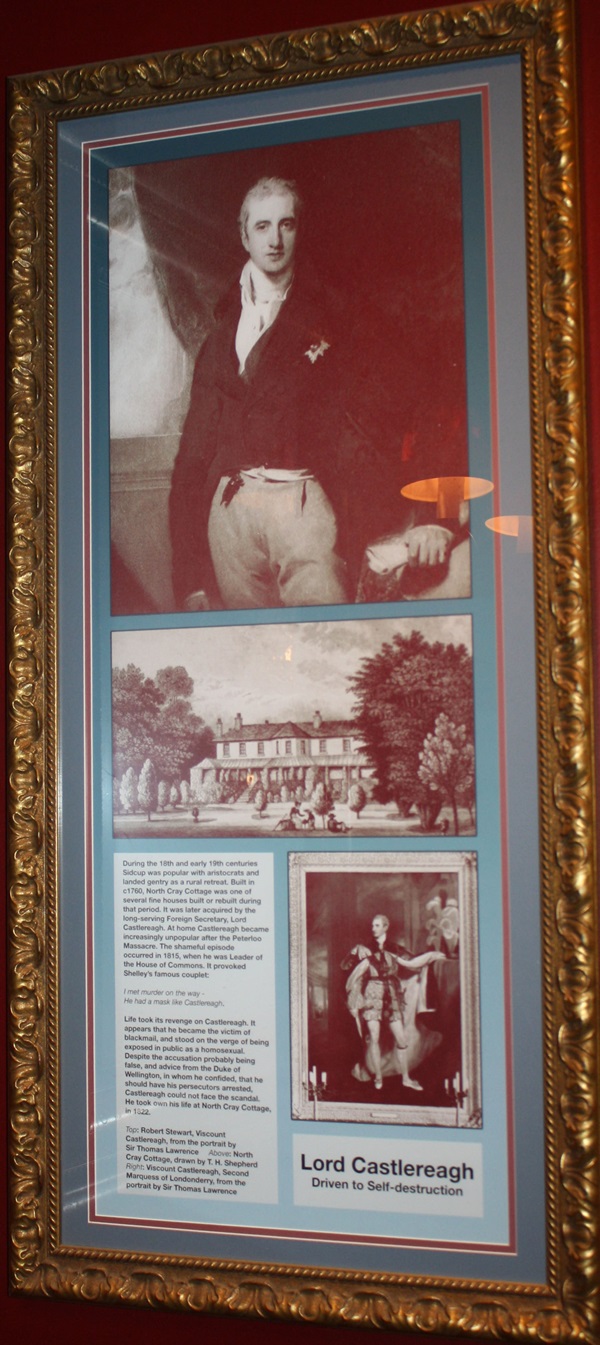

Prints, illustration and text about Lord Castlereagh.

The text reads: During the 18th and early 19th centuries Sidcup was popular with aristocrats and landed gentry as a rural retreat. Built in c1760 North Cray Cottage was one of several fine houses built or rebuilt during that period. It was later acquired by the long-serving Foreign Secretary, Lord Castlereagh. At home Castlereagh became increasingly unpopular after the Peterloo Massacre. The shameful episode occurred in 1815, when he was Leader of the House of Commons. It provoked Shelley’s famous couplet:

I met murder on the way –

He had a mask like Castlereagh.

Life took its revenge on Castlereagh. It appears that he became the victim of blackmail, and stood on the verge of being exposed in public as a homosexual. Despite the accusation probably being false, and advice from the Duke of Wellington, in whom he confided, that he should have his persecutors arrested, Castlereagh could not face the scandal. He took own his life at North Cray Cottage, in 1822.

Top: Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh, from the portrait bySir Thomas Lawrence

Above: North Cray Cottage, drawn by T H Shepherd

Right: Viscount Castlereagh, Second Marquess of Londonderry, from the portrait by Sir Thomas Lawrence.

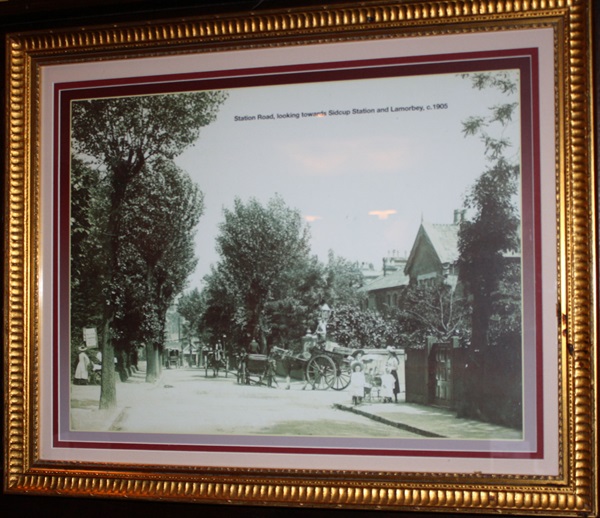

A photograph of Station Road, looking towards Sidcup Station and Lamorbey, c1905.

An acrylic painting entitled Broad Stripe, by Terry Chipp.

“The designs are based on a free composition of tailoring pattern shapes. Each painting has been built on a bed of Gesso with many layers of acrylic paint applied and partially removed to bring out the textures and colour blends”.

Terry Chipp has carried out commissions and exhibited his work widely across the UK and more recently in the United States. His paintings and drawings are in private collections around the world.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.