Pub history

The Standing Order

For many years, this grade II listed red-brick building was a branch of Lloyds Bank. Before 1963 (and since the early 1890s), it had housed O’Clee’s butcher’s business. Mr O’Clee was the first person in Stevenage to own a car. Earlier still, in the 1830s, 33 High Street was occupied by Mrs Alice Fisher who ran a Ladies’ Boarding School. She seems to have retired by 1851 and was still living at this address 10 years later.

33 High Street, Stevenage, Hertfordshire, SG1 3AU

The name of this pub recalls that this building was a bank from the early 1960s into the 1990s.

Prints and text about The Standing Order.

The text reads: The name of this J D Wetherspoon pub recalls that this building was occupied by a branch of Lloyds Bank from 1963 until recently. The origins of Lloyds can be traced to 18th century Birmingham. John Taylor, a Unitarian manufacturer of buttons and japanned goods, set up in partnership with a Quaker ironmonger, Sampson Lloyds, in 1765.

A private bank, Taylors & Lloyds operated only in Birmingham until the mid-19th century. The sons of the original partners had opened a bank in London, and when Lloyds absorbed this in 1884, they also acquired their famous Black Horse symbol.

Following its merger with the Trustee Savings Bank, Lloyds became Lloyds TSB. The TSB traces its origins to Reverend Henry Duncan, who opened his Savings Bank near Dumfries in 1810.

From the early 19th century, until Lloyds took over, 33 High Street was a butcher’s shop. First run by Joseph Moulden, the business was taken over in the 1890s, by FE O’Clee. Mr O’Clee made deliveries by horse and cart. His son Harry, possibly the first person in the town to own a car, replaced it with a motor-cycle combination.

Top: O’Clee’s butcher’s shop in 1900

Left: above, O’Clee’s delivery cart, c1903, below, the side care combination, c1930.

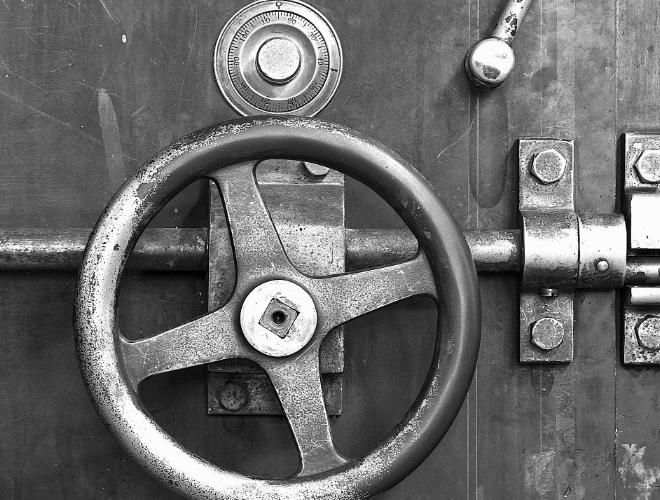

Prints and text about Ellen Terry and Gordon Craig.

The text reads: One of the greatest of theatrical designers, Edward Gordon Craig was born in Stevenage in 1872. His mother was Ellen Terry, the leading Shakespearean actress of her day.

Ellen’s marriage to the painter George Frederick Watts had failed, and she was living with Edward Gordon in Wheathampstead. She had begun her theatrical career in infancy, and appeared at London’s Prince’s Theatre, aged eight, in The Winter’s Tale.

Returning to the stage in the mid-1870s, partnered by actor-manager Sir Henry Irving, she came to dominate the English-speaking theatre. In 1903, she left Irving to work with her son, but had more success in parts written for her by George Bernard Shaw and JM Barrie.

After eight years with Irving, Gordon Craig retired from acting at the age of 25 to become a stage designer. His productions, which emphasised the players and simplified scenery, were unpopular in England, but brought him fame in Germany, Italy and Russia.

After travelling through Europe with the exotic dancer Isadora Duncan, he settled in Italy in 1906. He wrote several influential books, notably The Art of the Theatre, and Towards a New Theatre. He also wrote a biography of his mother, who was awarded the DBE in 1925.

Left: Ellen Terry

Above: top left, Gordon Craig in 1895, right, Craig aged 17 on stage with his mother, bottom left, Craig in 1907.

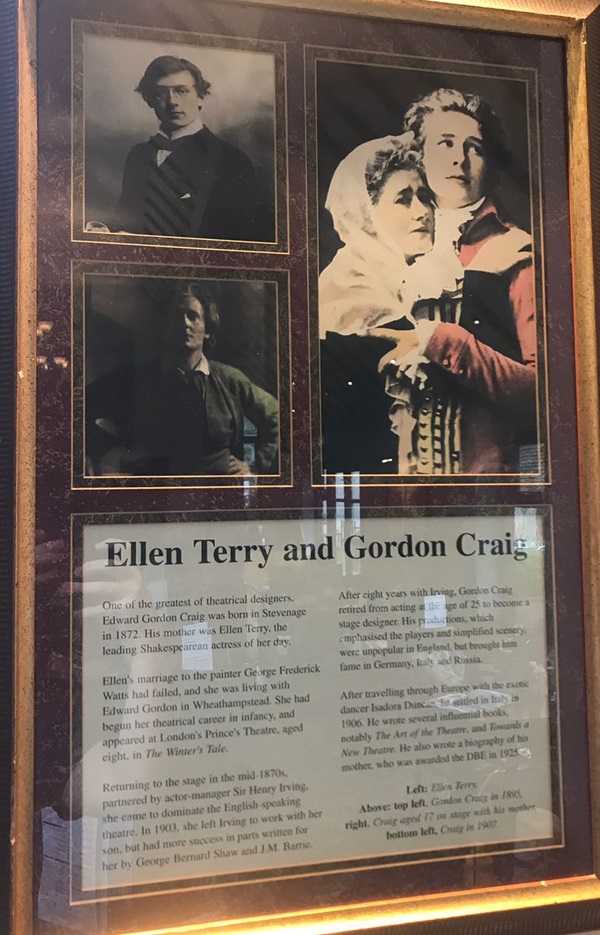

An illustration and text about the Great North Road.

The text reads: A track from prehistoric times, the route north from London was paved and straightened by the Romans. In the 13th century, the settlement beside St Nicholas’ Church moved down beside the road to take the trading opportunities offered by travellers.

In 1281, King Edward I granted a weekly market and annual fair to the town, under the Lord of the Manor, the Abbot of Westminster.

Middle Row developed from market stalls, slowly replaced by permanent structures. Some of the High Street’s oldest buildings date back to a time when rich London merchants built country houses conveniently close to the city. Travellers included the author Daniel Defoe, and Samuel Pepys, Secretary for the Navy.

Pepys wrote in his diary in 1667 that he stayed at the Swan Inn and enjoyed a game of bowls on the Green.

The Great North Road was ‘turnpiked’ from 1720. This privatisation led more inns to cater for stage-coach passengers. The first coach in regular service was the Perseverance, which ran from Smithfield to Hitchin.

Stevenage’s prosperous coaching trade, based on its role as the first main stop on the route north from London, declined when the Great Northern Railway opened in 1850.

Above: Boarding a stage coach, by Hogarth

Right: top, stage coach passengers at breakfast, below left, Edward I, below right, Samuel Pepys.

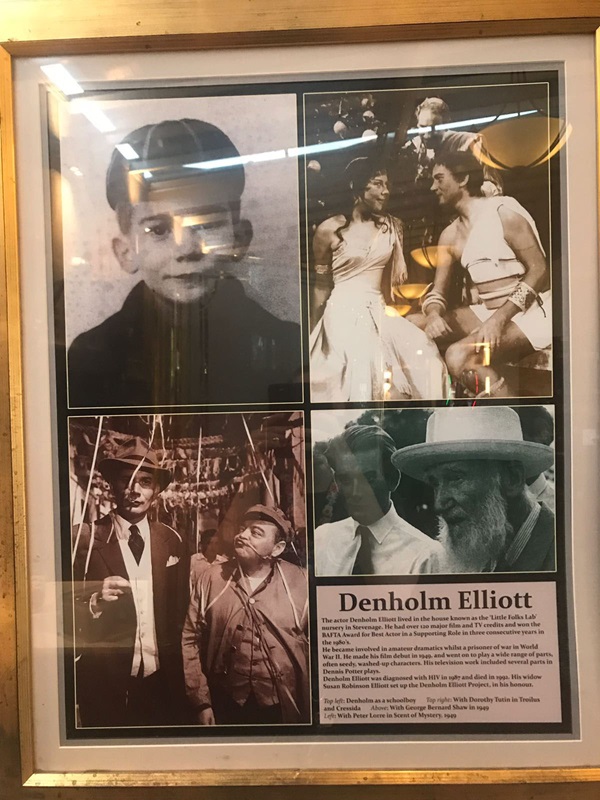

Photographs and text about Denholm Elliot.

The text reads: The actor Denholm Elliot lived in the house known as the ‘Little Folks Lab’ nursery in Stevenage. He had over 120 major film and TV credits and won the BAFTA Award for Best Actor in a Supporting Role in three consecutive years in the 1980s.

He became involved in amateur dramatics whilst a prisoner of war in World War II. He made his film debut in 1949, and went on to play a wide range of parts, often seedy, washed-up characters. His television work included several parts in Dennis Potter plays.

Denholm Elliot was diagnosed with HIV in 1987 and died in 1992. His widow Susan Robinson Elliot set up the Denholm Elliot Project, in his honour.

Top left: Denholm as a schoolboy

Top right: With Dorothy Tutin in Troilus and Cressida

Above: With George Bernard Shaw in 1949

Left: With Peter Lorre in Scent of Mystery, 1949.

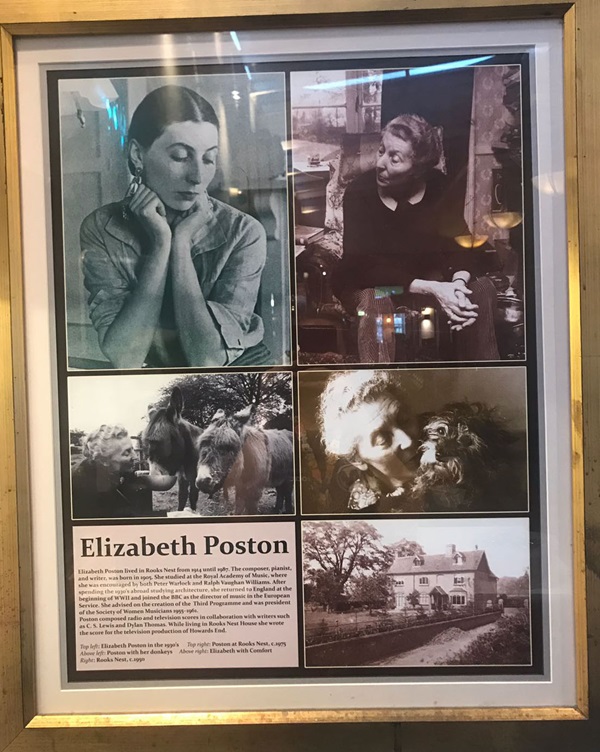

Photographs and text about Elizabeth Poston.

The text reads: Elizabeth Poston lived in Rooks Nest from 1914 until 1987. The composer, pianist, and writer, was born in 1905. She studied at the Royal Academy of Music, where she was encouraged by both Peter Warlock and Ralph Vaughan Williams. After spending the 1930s abroad studying architecture, she returned to England at the beginning of WWII and joined the BBC as the director of music in the European Service. She advised on the creation of the Third Programme and was president of the Society of Women Musicians 1955-61.

Poston composed radio and television scores in collaboration with writers such as CS Lewis and Dylan Thomas. While living in Rooks Nest house she wrote the score for the television production of Howards End.

Top left: Elizabeth Poston in the 1930s

Top right: Poston at Rooks Nest, c1975

Above left: Poston with her donkeys

Above right: Elizabeth with Comfort

Right: Rooks Nest, c1950.

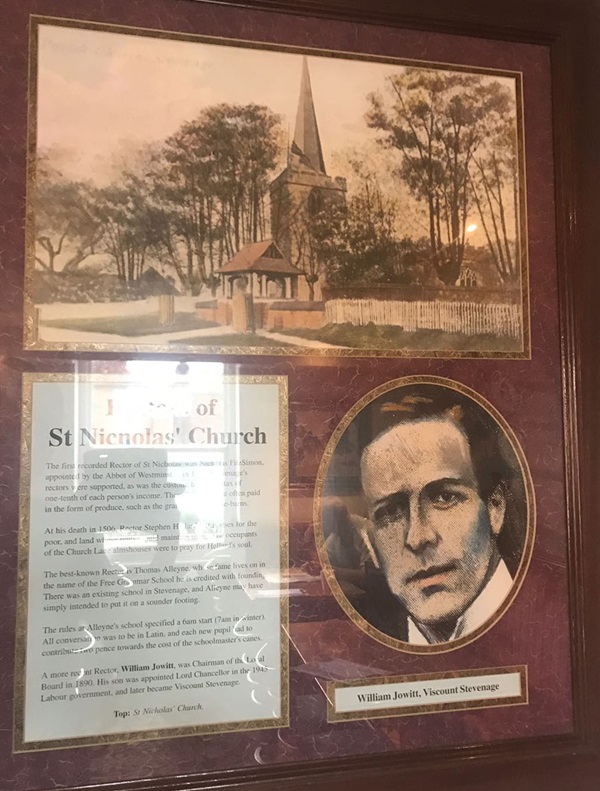

A print and text about St Nicholas’ Church.

The text reads: The first recorded Rector of St Nicholas’ was Nicholas FitzSimon, appointed by the Abbot of Westminster, in 1213. Stevenage’s rectors were supported, as was the custom, by a local tax of one-tenth of each person’s income. These “tithes” were often paid in the form of produce, such as the grain stored in tithe-barns.

At his death in 1506, Rector Stephen Hellard left houses for the poor, and land whose rents would maintain them. The occupants of the Church Lane almshouses were to pray for Hellard’s soul.

The best-known Reactor is Thomas Alleyne, whose fame lives on in the name of the Free Grammar School he is credited with founding. There was an existing school in Stevenage, and Alleyne may have simply intended to put it on a sounder footing.

The rules at Alleyne’s school specified a 6am start (7am in winter). All conversation was to be in Latin, and each new pupil had to contribute two pence towards the cost of the schoolmaster’s canes.

A more recent Rector, William Jowitt, was chairman of the local board in 1890. His son was appointed Lord Chancellor in the 1945 Labour government, and later became Viscount Stevenage.

Top: St Nicholas’ Church.

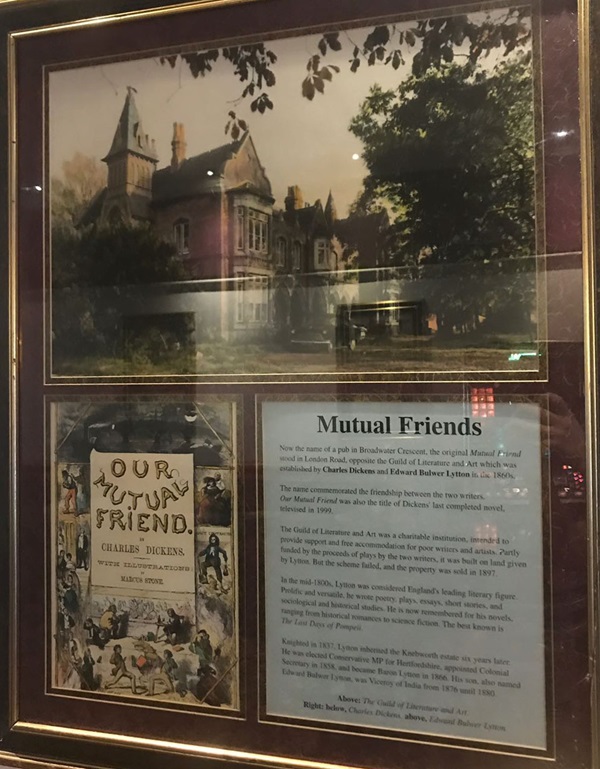

Prints and text about Charles Dickens and Edward Bulwer Lytton.

The text reads: Now the name of a pub in Broadwater Crescent, the original Mutual Friend stood in London Road, opposite the Guild of Literature and Art which was established by Charles Dickens and Edward Bulwer Lytton in the 1860s.

The name commemorated the friendship between the two writers. Our Mutual Friend was also the title of Dickens’ last completed novel, televised in 1999.

The Guild of Literature and Art was a charitable institution, intended to provide support and free accommodation for poor writer and artists. Partly funded by the proceeds of plays by the two writers, it was built on land given by Lytton. But the scheme failed, and the property was sold in 1897.

In the mid-1800s, Lytton was considered England’s leading literary figure. Prolific and versatile, he wrote poetry, plays, essays, short stories, and sociological and historical romances to science fiction. The best known is The Last Days of Pompeii.

Knighted in 1837, Lytton inherited the Knebworth estate six years later. He was elected Conservative MP for Hertfordshire, appointed Colonial Secretary in 1858, and became Baron Lytton in 1866. His son, also named Edward Bulwer Lytton, was Viceroy of India from 1876 until 1880.

Above: The Guild of Literature and Art

Right: below, Charles Dickens, above, Edward Bulwer Lytton.

Prints and text about different businesses on High Street.

The text reads: During the 1830s, 33 High Street was occupied by Mrs Alice Fisher, who ran a ladies boarding school. During the 1870s, no.33 housed J Moulden’s butchers shop. In 1904 the house is listed under FE O’Clee, also a butcher. Mr O’Clee made deliveries by horse and cart. His son Harry, possibly the first person in the town to own a car, replaced it with a motor-cycle combination. The O’Clees remained in possession until 1963 when no.33 became a branch of Lloyds Bank Ltd.

The origins of Lloyds can be traced to 18th century Birmingham. John Taylor, a Unitarian manufacturer of buttons and japanned goods, set up in partnership with a Quaker ironmonger, Sampson Lloyds, in 1765.

A private bank, Taylors & Lloyds operated only in Birmingham until the mid-19th century. The sons of the original partners had opened a bank in London, and when Lloyds absorbed this in 1884, they also acquired their famous Black Horse symbol.

Following its merger with the Trustee Savings Bank, Lloyds became Lloyds TSB.

Left: John Taylor II, 1738-1814

Top left: Howard Lloyd, 1837-1920

Top right: Sir Thomas Salt, Chairman of Lloyds, 1886-98

Above: ‘The Cashier’s Alarm Signal’, from Punch, 1914

A photograph of Six Hills, Stevenage, c1910.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.