Pub history

The Royal Oak

The Royal Oak is said to be around 300 years old. The round arch carriage entrance on the left-hand side once led to a cobbled stable yard which extended through to Princes Street. In the schedule of listed buildings, The Royal Oak is described as being of late 18th-/early 19th-century origin, refronted in the late 19th century.

The Royal Oak is said to be around 300 years old. The round arch carriage entrance on the left-hand side once led to a cobbled stable yard which extended through to Princes Street. In the schedule of listed buildings, The Royal Oak is described as being of late 18th-/early 19th-century origin, refronted in the late 19th century.

Photographs and text about ancient ruins

The text reads: Maiden Castle, to the southwest of Dorchester, is the largest and most complex hillfort in Britain. It was home to several hundred people in the Iron Age (800 BC – AD 43). It was first laid out in 600 BC over the remains of a Neolithic settlement. Around 450 BC, it was enlarged. The vast multiple ramparts now enclose an area the size of 50 football pitches. In AD 43, it was taken by the Roman army, and its inhabitants moved to the new town of Durnovaria, modern Dorchester. In the sixth century, it was abandoned.

Maumbury Rings is a Neolithic henge in the south of Dorchester. In around AD 100, 2,500 years after its construction, the Romans adapted it as an amphitheatre for the citizens of Durnovaria (Dorchester). The current layout of the site dates from the English Civil War (1642–51), when it was used as an artillery fort. Later, it was used for public executions. In 1685, judge Jeffreys ordered 80 rebels from the Monmouth Rebellion to be executed here.

Top: The service in Maumbury Rings for the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria, 1897

Centre, left: Maiden Castle in 1937

Centre, right: Maumbury Rings, c1935

Left: An artist’s impression of the settlement at Maiden Castle

Above: An engraving of Maumbury Rings

Illustrations and text about the Royal Oak

The text reads: The Royal Oak, here in Dorchester, was once a leading coaching inn thought to date from the late 1700s. Its entrance led to a stable yard. An exit into Princes Street, under the hayloft of the Greyhound, made a one-way system for carriages.

The Royal Oak is Britain’s second most popular pub name (after The Red Lion). In order to appear loyal on the return of the monarchy in 1660, many landlords named – or renamed – their pubs after King Charles II’s royal hiding place.

Charles had returned from exile after his father’s execution in 1649. Crowned in Scotland, he invaded England, only to be defeated at the Battle of Worcester. He then fled to Boscobel House, in Shropshire, where he hid in an oak tree to avoid capture by Parliamentary troops. The monarchy was restored in 1660, on his birthday, 29 May, which was made a day of thanksgiving. It became known as Oak Apple Day, when people wore oak sprigs in their clothes.

Above: King Charles II and the royal oak

Left: The royal escape after the Battle of Worcester

Photographs and text about Thomas Hardy’s novels

The text reads: Hardy immortalized Dorchester as Casterbridge in his novels. Other local places that featured in his life and work include the following (fictional names in brackets):

Stinsford (Mellstock)

Thomas Hardy was christened at the church here, and his first wife Emma is buried in the churchyard. Hardy himself wanted to be buried with her, but only his heart is interred in Emma’s grave.

Higher Bockhampton (Upper Mellstock)

The lovely thatched Hardy’s Cottage is the author’s birthplace – now run by the National Trust.

Bere Regis (Kingsbere)

The town features in Tess of the d’Urbervilles and Far From the Madding Crowd. Tess set up her family’s bed under the Turberville window in the south wall of the church, and inside the church are the tombs of the Turbervilles.

Athelhampton (Athelhull)

Hardy’s father worked on the restoration of the superb medieval hall at Athelhampton, and Hardy himself painted a watercolour of the house.

Puddletown (Weatherbury)

Hardy’s grandfather and great-grandfather were Puddletown natives, and the church gallery was celebrated by Hardy in Under the Greenwood Tree. In Far From the Madding Crowd, Troy spent the night in the church porch.

Cerne Abbas (Abbot’s Cernel)

The village, more famous for the ancient figure of a giant carved into the hillside, featured in The Woodlanders and Tess of the d’Urbervilles.

Top (from left to right): High East Street, Dorchester, c1900; A Puddletown shoemaker employed by Hardy’s cousin, John Antell, 1899; Bere Regis, c1885

Above (from left to right): Winterbourne Steepleton, c1890; Town crier Stephen Burden, cousin of Hardy’s mother, in Puddletown, c1890; Hardy’s birthplace; High West Street, Dorchester, c1860; South Walks, Dorchester, c1860, near to the architect’s office where Hardy worked

Left: Puddletown, 1891

Right: The Wood-Homer family outside Athelhampton, c1885

Photographs and text about the Herbert family of Dorchester

The text reads: The Herbert family story opens with John William Herbert, a respectable horse dealer who worked between Ireland and the West Country.

His son Jack followed him into the livestock market trade with a ‘joy wheel’ – an early form of the roundabout where riders had to cling on until they fell off. Jack married showman’s daughter Sally Newman. They had five children and continued working the fairs with the joy wheel, to which they added a shooting gallery, snake show, roll-the-penny and hoopla.

After Sally’s death at the age of 34, Jack married Mildred Moore, 22 years his junior, after a three-month courtship. They went on to have 11 children, after making their home in St Georges Road, Dorchester, where the family still reside today.

During the Second World War, the government introduced holidays at home fairs to boost national morale; this is when the Herbert family held their fair in the Market Car Park, Dorchester.

The steam engine Majestic was the pride of the family, even when she tipped over on the road near Dorchester, closing the carriageway for three weeks until she could be moved. Majestic left Dorchester in 1947, when the Herbert family sold the engine for preservation.

Such was her importance in the world of steam that Majestic was immortalised as a model by toymakers Corgi, and a copy of the miniature was presented to family member Edward Herbert in 2012 at the Great Dorset Steam Fair in front of the original engine.

The story of the Herbert family comes from Kay Townsend’s book The Herberts of Dorchester. Her first book – Townsends, a Showman’s Story – was about her own family, based in Weymouth.

The Townsend family and the Herberts regularly travelled together, especially for Portland fair. Kay has known the Herbert’s all her life. She is semi-retired from travelling now and gives talks on the subject of fairground life.

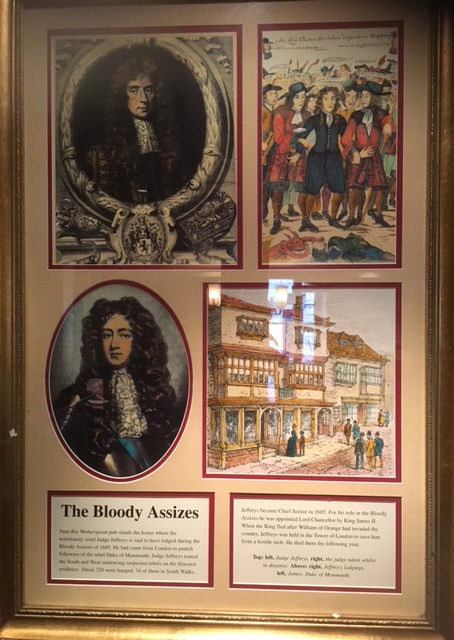

Illustrations and text about the Bloody Assizes

The text reads: Near this Wetherspoon pub stands the house where the notoriously cruel Judge Jeffreys is said to have lodged during the Bloody Assizes of 1685. He had come from London to punish followers of the rebel Duke of Monmouth. Judge Jeffreys toured the south and west, sentencing suspected rebels on the flimsiest evidence. About 320 were hanged, 74 of them in South Walks.

Jeffreys became chief justice in 1685. For his role in the Bloody Assizes he was appointed Lord Chancellor by King James II. When the King fled after William of Orange had invaded the country, Jeffreys was held in the Tower of London to save him from a hostile mob. He died there the following year.

Top, left: Judge Jeffreys

Top, right: The judge taken whilst in disguise

Above, right: Jeffrey’s lodgings

Above, left: James, Duke of Monmouth

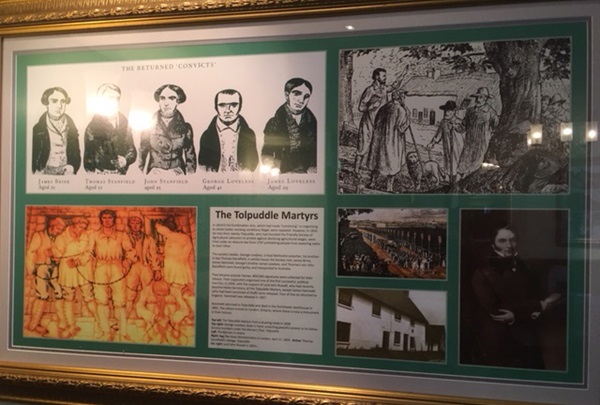

Illustrations and text about the Tolpuddle Martyrs

The text reads: In 1824/5, the Combination Acts, which had made combining or organising to obtain better working conditions illegal, were repealed. However, in 1834, six men from nearby Tolpuddle, who had founded the Friendly Society of Agricultural Labourers to protest against declining agricultural wages, were tried under an obscure law from 1797 prohibiting people from swearing oaths to each other.

The society’s leader, George Loveless, a local Methodist preacher; his brother-in-law Thomas Standfield, in whose house the society met; James Brine; James Hammett; George’s brother James Loveless; and Thomas’s son John Standfield were found guilty and transported to Australia.

They became popular heroes. Eight hundred thousand signatures were collected for their release. Their supporters organised one of the first successful political marches. In 1836, with the support of Lord John Russell, who had recently become home secretary, all the Tolpuddle Martyrs, except James Hammett (who had been convicted of theft) were released. Four of the six returned to England. Hammett was released in 1837.

Hammett returned to Tolpuddle and died in the Dorchester workhouse in 1891. The others moved to London, Ontario, where there is now a monument in their honour.

Top, left: The Tolpuddle Martyrs from a drawing made in 1838

Top, right: George Loveless, book in hand, preaching peaceful protest to his fellow society members under the Martyr’s Tree, Tolpuddle

Left: The Martyrs in chains

Right, top: the mass demonstration in London, April 21, 1834

Right, below: Thomas Standfield’s cottage, Tolpuddle

Far right: Lord John Russell in 1854

Photographs and text about Thomas Hardy

The text reads: Thomas Hardy was born in Higher Bockhampton, just three miles outside Dorchester, in 1840. He went to school in the town, and in 1856 he started working for John Hicks, a local architect at 39 South Street.

After working as an architect’s assistant in London, he moved back to Dorset, and in 1871 published his first novel, Desperate Remedies. Two more novels, A Pair of Blue Eyes and Under the Greenwood Tree, quickly followed in 1872 and 1873. A year later, he married Emma Gifford, and in the same year became a full time writer.

Hardy designed the house Max Gate, which was built to his own specifications by his brother on the edge of Dorchester in 1885, where he lived and wrote until his death in 1928, and where Tess of the d’Urbervilles, Jude the Obscure and The Mayor of Casterbridge were written.

In later life, he published eight volumes of poetry, his last being Winter Words, in 1928, the year he died, aged 87.

A statue of Hardy, sculpted by Eric Kennington, was erected in 1931, and is located at the top of town.

Above, left: Thomas Hardy aged 19

Above, right: Hardy (with his bicycle), and his wife Emma with her nephew, outside Max Gate, c1900

Left: Hardy in his garden at Max Gate, 1913

Right: Thomas Hardy, c1880

An Eldridge Pope emblem from when The Royal Oak was run by the local brewery, which was located down the road

The hayloft, recently refurbished, over the rear entrance into what would have been the yard and is now a carpark

The site of the original coach houses, which have been rebuilt over time

External photograph of the building – main entrance