Pub history

The Red Well

The Red Well was the most famous of several springs in Wellingborough. Visited by royalty, it has since given its name to the Redwell area of the town and this Wetherspoon pub.

The Red Well was the most famous of several springs in Wellingborough. Visited by royalty, it has since given its name to the Redwell area of the town and this Wetherspoon pub.

Artwork depicting villagers enjoying the springs

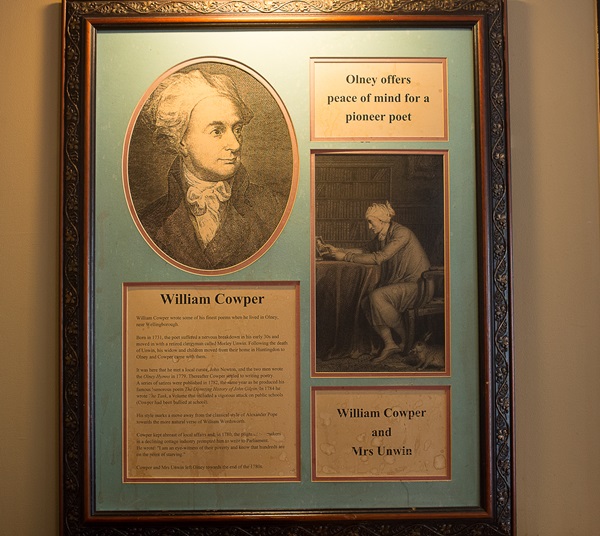

Illustrations and text about William Cowper

The text reads: William Cowper wrote some of his finest poems when he lived in Olney, near Wellingborough.

Born in 1731, the poet suffered a nervous breakdown in his early thirties and moved in with a retired clergyman called Morely Unwin. Following the death of Unwin, his widow and children moved from their home in Huntingdon to Olney, and Cowper came with them.

It was here that he met a local curate, John Newton, and the two men wrote the Olney Hymns in 1779. Thereafter, Cowper settled to writing poetry. A series of satires was published in 1782, the same year as he produced his famous humorous poem The Diverting History of John Gilpin. In 1784, he wrote The Task, a volume that included a vigorous attack on public schools (Cowper had been bullied at school).

His style marks a move away from the classical style of Alexander Pope towards the more natural verse of William Wordsworth.

Cowper and Mrs Unwin left Olney towards the end of the 1780s.

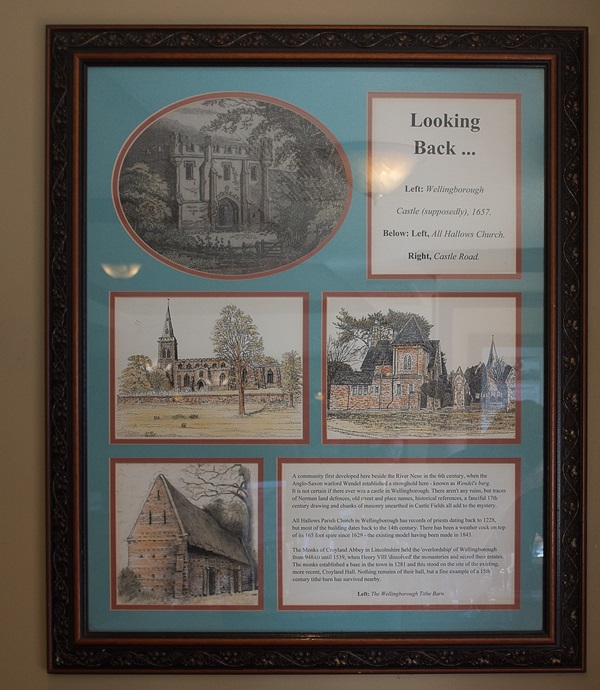

Illustrations and text about the history of Wellingborough

The text reads: A community first developed here beside the River Nene in the 6th century, when the Anglo-Saxon warlord Wendel established a stronghold here – known as Wendel’s burg. It is not certain if there ever was a castle in Wellingborough. There aren’t any ruins, but traces of Norman land defences, old street and place names, historical references, a fanciful 17th-century drawing, and chunks of masonry unearthed in Castle Fields all add to the mystery.

All Hallows Parish Church in Wellingborough has records of priests dating back to 1228, but most of the building dates back to the 14th century. There has been a weather cock on top of its 165-foot spire since 1629 – the existing model having been made in 1843.

The Monks of Croyland Abbey in Lincolnshire held the ‘overlordship’ of Wellingborough from AD 948 until 1539, when Henry VIII ‘dissolved’ the monasteries and seized their estates. The monks established a base in the town in 1281, and this stood on the site of the existing, more recent, Croyland Hall. Nothing remains of their hall, but a fine example of a 15th-century tithe barn has survived nearby.

Left: The Wellingborough Tithe Barn

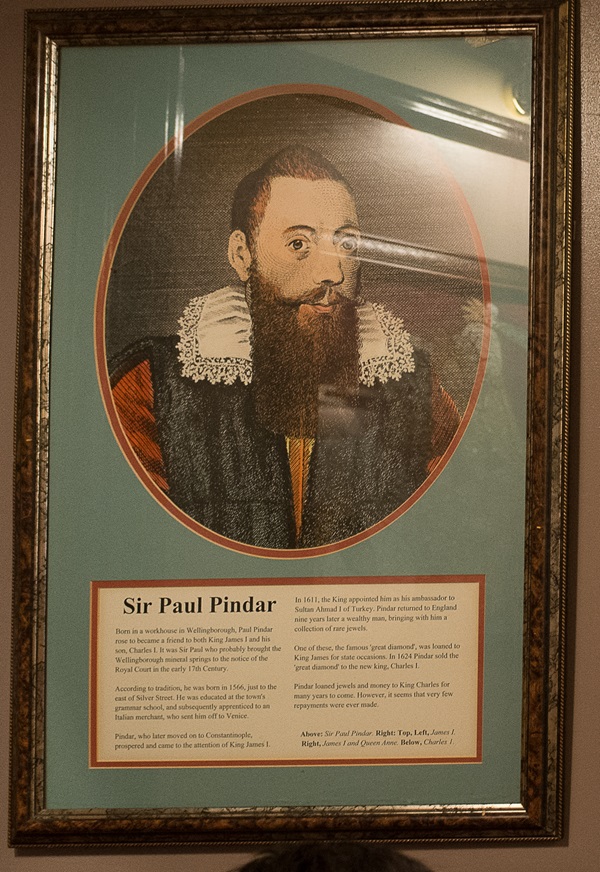

An illustration and text about Sir Paul Pindar

The text reads: Born in a workhouse in Wellingborough, Paul Pindar rose to become a friend to both King James I and his son, Charles I. It was probably Sir Paul who brought the Wellingborough mineral springs to the notice of the Royal Court in the early 17th century.

According to tradition, he was born in 1566, just to the east of Silver Street. He was educated at the town’s grammar school and subsequently apprenticed to an Italian merchant, who sent him off to Venice.

Pindar, who later moved on to Constantinople, prospered and came to the attention of King James I.

In 1611, the King appointed him as his ambassador to Sultan Ahmad I of Turkey. Pindar returned to England nine years later a wealthy man, bringing him with a collection of rare jewels.

One of these, the famous ‘great diamond’ was loaned to King James for state occasions. In 1624, Pindar sold the ‘great diamond’ to the new king, Charles I.

Pindar loaned jewels and money to King Charles for many years to come. However, it seems that very few repayments were ever made.

Above: Sir Paul Pindar

An illustration and text about the Great Fire of Wellingborough

The text reads: The 28 July in 1738 was a hot, dry day with a buffeting breeze – ideal conditions for the terrible Great Fire of Wellingborough.

The blaze started when a cinder dropped from a fire at a dyer’s shop on Silver Street. It quickly spread to destroy over 200 houses and 800 shops, barns, stables and other buildings in just one afternoon.

Desperate townsfolk did their best to battle the blaze. Others took refuge in the church, where the heat of the flames caused the lead roofing to melt and drip to the ground as the fire crept ever closer to its walls.

The noble efforts of one 60-year-old woman, Hannah Sparke, made her the hero of the day. Water being scarce, Hannah had the ‘malt liquors’ in her cellar emptied on to the flames, and threw blankets soaked in beer over the roof of her Pebble Lane home.

Hannah’s spirited intervention is said to have stemmed the ravaging fire and played a vital role in saving the church.

Hannah became a legend in her own lifetime and lived to the age of 107. When she reached her centenary, she was carried around Market Square in a chair by the devoted people of Wellingborough.

Above: Wellingborough as it appeared before the Great Fire

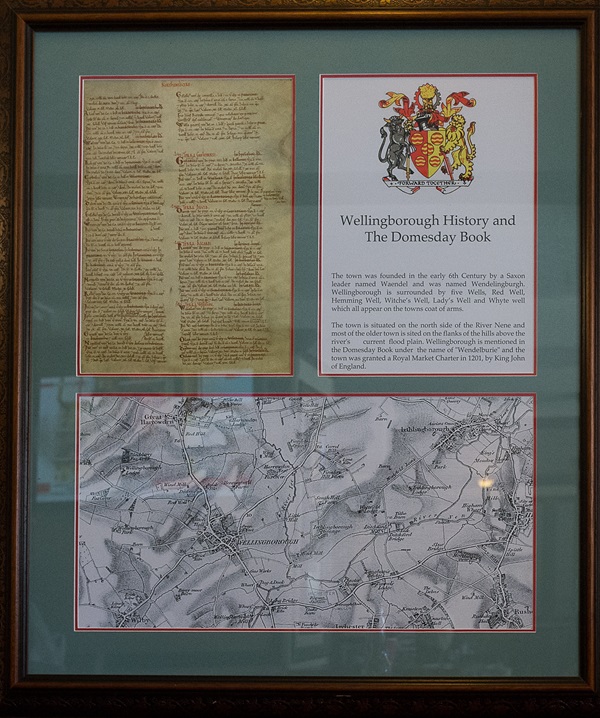

Prints and text about the history of Wellingborough

The text reads: The town was founded in the early 6th century by a Saxon leader named Wændel and was named Wendelingburgh. Wellingborough is surrounded by five wells: Red Well, Hemming Well, Witches’ Well, Lady’s Well and Whyte Well, which all appear on the town’s coat of arms.

The town is situated on the north side of the River Nene, and most of the older town is sited on the flanks of the hills above the river’s current flood plain. Wellingborough is mentioned in the Domesday Book under the name of ‘Wendelburie’, and the town was granted a Royal Market Charter in 1201 by King John of England.

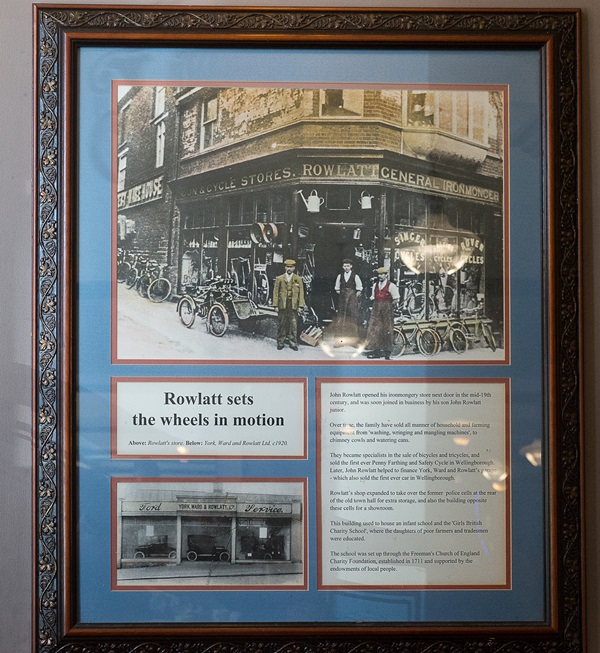

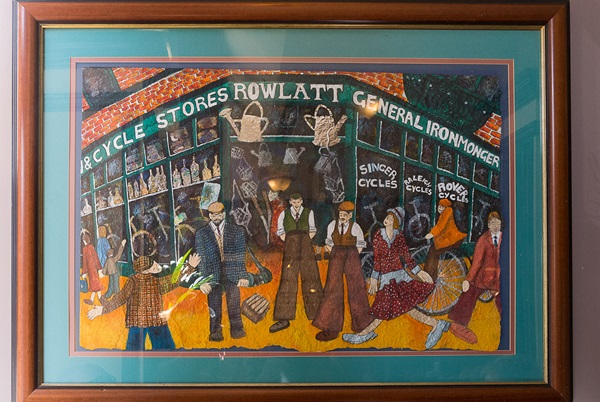

Prints and text about Rowlatts

The text reads: John Rowlatt opened his ironmongery store next door in the mid-19th century and was soon joined in business by his son John Rowlatt junior.

Over time, the family have sold all manner of household and farming equipment from ‘washing, wringing and mangling machines’ to chimney cowls and watering cans.

They became specialists in the sale of bicycles and tricycles, and sold the first ever Penny Farthing and Safety Cycle in Wellingborough. Later, John Rowlatt helped to finance York, Ward and Rowlatt’s garage – which also sold the first ever car in Wellingborough.

Rowlatt’s shop expanded to take over the former police cells at the rear of the old town hall for extra storage, and also the building opposite these cells for a showroom.

This building used to house an infant school and the ‘Girls British Charity School’, where the daughters of poor farmers and tradesmen were educated.

The school was set up through the Freeman’s Church of England Charity Foundation, established in 1711 and supported by the endowments of local people.

External photograph of the building – main entrance