Pub history

The Paramount

Oxford Street was once crowded with theatres and cinemas, including The Paramount. Built in 1930, this showpiece ‘picture palace’ was later replaced by the Odeon cinema, next to this Wetherspoon pub. Manchester’s first film shows took place at the St James Theatre, Oxford Street, in 1896. The Picture House – diagonally opposite this Wetherspoon pub – was the city’s first purpose-built cinema (1911).

33–35 Oxford Street, Manchester, M1 4BH

Oxford Street was once crowded with theatres and cinemas, including The Paramount. Built in 1930, this showpiece ‘picture palace’ was later replaced by the Odeon cinema, next to this Wetherspoon pub. Manchester’s first film shows took place at the St James Theatre, Oxford Street, in 1896. The Picture House – diagonally opposite this Wetherspoon pub – was the city’s first purpose-built cinema (1911).

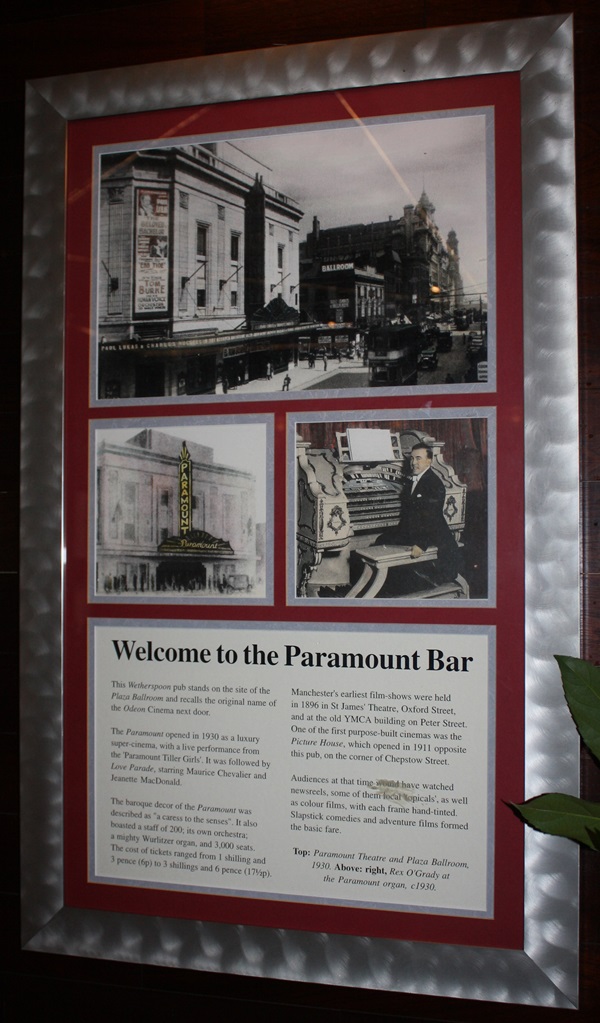

Framed photographs and text about The Paramount Bar.

The text reads: The Wetherspoon pub stands on the site of the Plaza ballroom and recalls the original name of the Odeon cinema next door.

The Paramount opened in 1930 as a luxury super-cinema, with a live performance from the ‘Paramount Tiller Girls’. It was followed by Love Parade, starring Maurice Chevalier and Jeanette MacDonald.

The baroque décor of the Paramount was described as “a caress to the senses”. It also boasted a staff of 200; its own orchestra; a mighty Wurlitzer organ, and 3000 seats. The cost of tickets ranged from 1 shilling and 3 pence (6p) to 3 shillings and 6 pence (17 ½ p).

Manchester’s earliest film shows were held in 1896 in St. James’ Theatre, Oxford Street, and at the old YMCA building on Peter Street. One of the first purpose-built cinemas was the Picture House, which opened in 1911 opposite this pub, on the corner of Chepstow street.

Audiences at that time would have watched newsreels, some of them local ‘topicals’, as well as colour films, with each frame hand-tinted. Slapstick comedies and adventure films formed the basic fare.

Top: Paramount Theatre and Plaza Ballroom in 1930

Above: right, Rex O’Grady playing at the Paramount organ in 1930.

Framed photographs of The Paramount theatre.

Top left: The Paramount, opened October 1930

Top right: The Paramount’s founder Wurlitzer

Right: The cinema as an Odeon in the mid-1960’s

Above and below: The Paramount’s lavish interior.

Framed photographs and text about Oxford Street.

The text reads: Oxford Street has always been the centre of Manchester’s entertainment industry.

When the Paramount opened in 1930 some live entertainment was mingled with the films. Next to it stood the Plaza Ballroom, where, besides summer dancing, there was also table tennis and billiards available. Further along the street stood the Hippodrome and beyond that place was the Princes Theatre. The Hippodrome was designed by the prolific Frank Matcham, and opened in 1904. In the 1930’s it was replaced by the Gaumont cinema.

From the 1930’s onwards there were several other cinemas, including the New Oxford Cinema, next to the Gaumont, and the Manchester News Theatre, which sometimes showed cartoon programmes for children.

At the junction with the Whitworth Street stood the Palace Theatre. Built in the early 1890’s, the Palace survived the decline of music-hall and re-invented itself as a venue for major productions such as opera, musicals and ballet.

Top left: An electric tram outside the Palace Theatre, Oxford Street, c1905

Top right: The Palace Theatre of Varieties, in the early 1900s

Centre right: The Hippodrome, c1907

Above: Queuing outside The Paramount cinema in c1940

Right: The Paramount’s interior viewed from the stage.

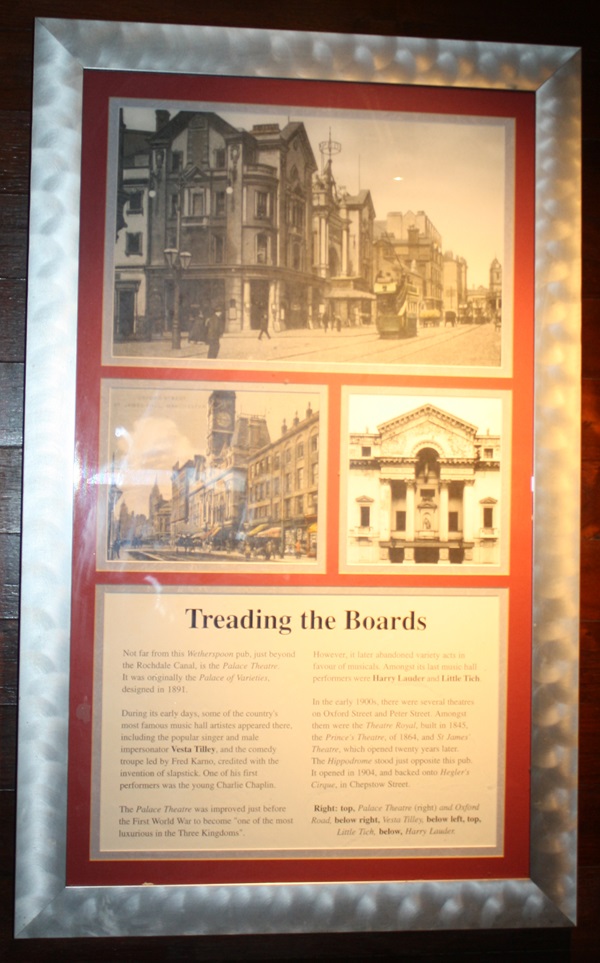

Framed photographs and text about The Palace Theatre.

The text reads: Not far from this Wetherspoon pub, just beyond the Rochdale Canal, is the Palace Theatre. It was originally the Palace of Varieties, designed in 1891.

During its early days, some of the country’s most famous music hall artistes appeared there, including the popular singer and male impersonator Vesta Tilley, and the comedy troupe led by Fred Karno, credited with the invention of slapstick. One of the first performers was the young Charlie Chaplin.

The Palace Theatre was improved just before the First World War to become “one of the most luxurious in the Three Kingdoms.”

However it later abandoned variety acts in favour of musicals. Amongst its last music hall performers were Harry Lauder and Little Tich.

In the early 1900’s there were several theatres on Oxford Street and Peter Street. Amongsth them were the Theatre Royal,built in 1845, the Prince’s Theatre, of 1864, and St James’ Theatre, which opened twenty years later. The Hippodrome stood just opposite this pub. It opened in 1904, and backed onto Hegler’s Cirque, in Chepstow Street.

Right: top, Palace Theatre (right) and Oxford Road

Below, right: Vesta Tilley

Below left, top, Little Tich

Below, Harry Lauder.

Framed photographs and text about Robert Donat.

The text reads: The actor Robert Donat, best known for his roles in

Alfred Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps And Goodbye, Mr Chips – for which he won an Academy Award for Best Actor – was born in Withington in 1905, and educated in Manchester’s Central High School for Boys.

Through his parents Ernst Emil Donat and Rose Alice he inherited a mixture of English, Polish, German and French characteristics.

He made his first stage appearance in 1921 and his film debut in 1932. His first great screen success came in The Private Life of Henry VIII.

He was likened by critics to Hollywood’s Clark Gable and Gary Cooper. The competition he saw off to win his Academy Award for Goodbye, Mr Chips (1939) included Clark Gable for Gone With The Wind, Laurence Olivier for Wuthering Heights, James Stewart for Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and Mickey Rooney for Babes in Arms.

According to Judy Garland, although she first sang “You Made Me Love You” for Clark Gable, she really wanted to sing it for Donat, her idol ever since she saw him in The Count of Monte Cristo (1934).

Chronic asthma limited Donat’s work to just 20 films. His final role was as the mandarin Yang Cheng in The Inn of the Sixth Happiness (1958).

Far left: Robert Donat as a baby

Left: Rose and Ernest Donat, his parents, 1937

Top left: As Richard Hannay, with Madeleine Carroll, in Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps

Centre left: With Margaret Leighton in The Winslow Boy

Top right: As Mr Chips in old age, in Goodbye Mr Chips

Above: In his last role, just weeks before his death, as the Chinese Mandarin in The Inn of the Sixth Happiness, with Ingrid Bergman.

Framed photographs and text about John Alcock and Arthur Brown.

The text reads: John Alcock & Arthur Brown, who made the very first transatlantic fight in 1919, spent their early years in Manchester, and both attended Manchester Central High School (but at different times).

Alcock was born in Old Trafford, His family then moved to Fallowfield. Brown was the son of American parents and was born in Glasgow. His family moved to Manchester when he was a child and lived in Chorlton-cum-Hardy.

By the outbreak of the World War in 1914, both men were involved in flying, Alcock in the Royal Naval Air Force and Brown in the Royal Flying Corps. By 1919, supported by the Vickers Company, who were to supply a plane, Alcock was set on flying across the Atlantic Ocean. At this point he met Brown, who agreed to be the navigator on the trip. The historic flight in a Vickers Vimy Rolls aeroplane began from St. John’s in Newfoundland on June 14th, 1919 and they arrived at Clifden in the Republic of Ireland the next morning – a distance of some 1960 miles in the then amazing time of just under 16 hours.

Both Alcock and Brown were knighted and awarded the sum of £10,000 by the London Daily Mail. A sculpture commemorating their flight stands at Manchester airport.

Top left: Brown and Alcock in Newfoundland

Left: Alcock during the London to Manchester Race, 1914

Top right: Brown and Alcock before the Atlantic flight

Right: Alcock receiving the £10,000 prize from Winston Churchill, Secretary State for War.

Framed photographs and text about Sir Edwin Alliott Verdon-Roe.

The text reads: Born in Patricroft in Manchester in 1877, Sir Edwin Alliott Verdon-Roe was to become a celebrated aircraft designer.

He served as an apprentice in with the Lancashire and Yorkshire railways and later went to study marine engineering at King’s college, London. His interest in birds and flight, led to the construction of flying models. In 1907 one of his designs won a major competition and a prize of £75. He used the money to build a full size aeroplane based on his winning model and in 1908 he flew the first British-built plane to fly under its own power. Alliott’s brother, Humphrey, who was later to marry Marie Stopes, helped him found the AVRO company (based on his own name and intials) in Manchester in 1910. AVRO became the first company ever to be registered as an airplane manufacturer.

He went on to build the famous AVRO 504 biplane in 1913, the most commonly used military aircraft in World War One, and copied by others all over the world.

When the Armstrong Siddeley Company took over AVRO in 1928, Roe moved into boat design and invented the flying boat, for which he was knighted in 1929.

Top left: Portrait of Sir Alliot Verdon-Roe in 1947

Top right: The AVRO 504K – the official training machine of the Royal Flying Corps

Right: A. V. R. preparing a prototype, 1909

Left: A. V. R. with an AVRO Triplane, 1910.

Framed photographs and text about Marie Stopes.

The text reads: Doctor Marie Stopes, world renowned pioneer of birth control for women, was the first female lecturer at the University of Manchester.

She was a ‘high-flyer’, having taken just 2 years to complete her degree in botany and zoology, (instead of the normal three), and then gained her doctorate which she completed in German.

Her marriage to Doctor Reginald Gates was annulled in 1916 on the grounds of non-consummation.

She learned about sex from books in the British museum. The realisation of her own ignorance, and that of most women of her day when they got married, led her to write her first and best-selling book ‘Married Love’ in 1918.

At the age of 37, in 1917, she married Manchester’s aircraft manufacturer Humphrey Verdon-Roe. In 1921 she opened her first birth control clinic.

Aimed at poor women, the clinic was free. Marie became the object of extreme and abusive criticism. Catholic clergy condemned her as a ‘criminal’. However, her work attracted awards as well as brickbats. She continued to be dogged by controversy in her professional and personal life until her death in 1958.

Top right: The first portrait of Marie Stopes in her robes as a Doctor of Science

Top left: Dr. Marie Stopes at the time of her second marriage

Above: Humprey Verdon-Roe, c.1917

Right: Marie Stopes in her laboratory, 1932

Left: Marie Stopes with her son Harry

Far left: Marie Stopes about to deliver a public lecture.

Framed photographs and text about The Free Trade Hall and Sir Charles Halle.

The text reads: The first Free Trade Hall was built of wood at St Peter’s Field opposite the site of the Peterloo and the Anti-Corn law demonstrations of 1819, on land given by the great reformer Richard Cobden.

The present structure, opened on 10th October 1856, was dedicated to the cause of free trade (then associated with liberalism rather than extreme capitalism). It was regularly filled to capacity by people coming to hear the great orators, the political reformers, the philosophers and the literary figures of the day.

The committee of the 1857 Arts Exhibition in Manchester invited Charles Halle to enlarge the old Gentleman’s Concerts Orchestra to give daily concerts during the exhibition. When the exhibition closed, Halle kept the orchestra together then began his famous concerts at the Free Trade Hall in January 1858, from which the Halle orchestra evolved.

Above and top right: Sir Charles Halle

Top left and left: The Free Trade Hall

Right: Peter Street, with the Free Trade Hall down the left hand side.

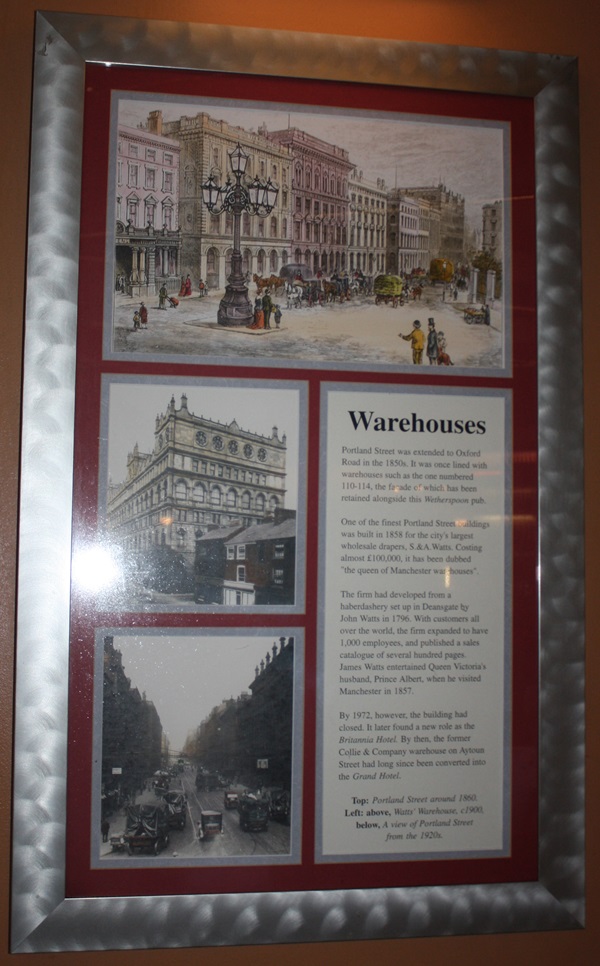

Framed drawings, photograph and text about Portland Street.

The text reads: Portland Street was extended to Oxford Road in the 1850s. It was once lined with warehouses such as the one numbered 110-114, the façade of which has been retained alongside this Wetherspoon pub.

One of the finest Portland street buildings was built in 1858 for the city’s largest wholesale drapers, S&A. Watts. Costing almost £100,000, it has been dubbed “the queen of Manchester warehouses”

The firm had developed from a haberdashery set up in Deansgate by John Watts in 1796. With customers all over the world, the firm expanded to have 1,000 employees, and published a sales catalogue of several hundred pages. James Watts contained Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert, when he visited Manchester in 1857.

By 1972, however, the building had closed. It later found a new role as the Britannia Hotel. By then, the former Collie & Company warehouse on Aytoun Street had long been converted into the Grand Hotel.

Top: Portland Street around 1860

Left: above, Watts’ Warehouse, c1900

Below, A view of Portland Street from the 1920s.

Framed photographs and text about The Manchester Ship Canal.

The text reads: The 36-mile (58km) long Manchester Ship Canal was designed to give the city of Manchester direct access to the sea. It was built between 1887 and 1894 at a cost of about £15 million (£1.27 billion as of 2010), and in its day was the largest navigational canal in the world.

The canal generally follows the original route of the rivers Mersey and Irwell, and along its course uses several sets of locks. The canal is able to accommodate a range of vessels, from coastal ships to inter-continental cargo liners, but it is not large enough for all modern vessels. A railway was built to transport goods to and from the docks located alongside the canal.

The canal is no longer considered to be an important shipping route, but it still carries about 6 million tons of freight each year. It is now operated under private ownership.

Top left: Workmen on the Ship Canal using an hydraulic riveting machine

Above: Latchford High Level railway bridge in 1890

Right: Letting in the water at Ellesmere Port

Left: The new steel Barton Aqueduct that replaced the 18th century original when the Ship Canal was built.

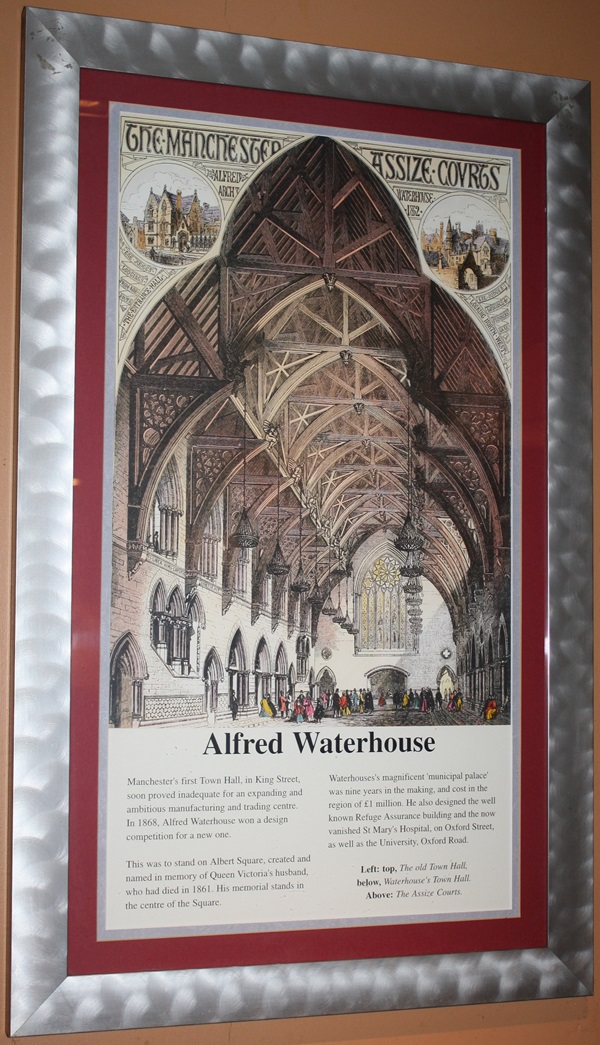

A framed drawing and text about Alfred Waterhouse.

The text reads: Manchester’s first Town Hall, in King Street, soon proved inadequate for an expanding and ambitious manufacturing and trading centre. In 1868, Alfred Waterhouse won a design competition for a new one.

This was to stand on Albert Square, created and named in memory of Queen Victoria’s husband, who had died in 1861. His memorial stands in the centre of the square.

Waterhouse’s magnificent ‘municipal palace’ was nine years in the making, and cost in the region of £1million. He also designed the well-known Refuge Assurance building and the now vanished St Mary’s Hospital, on Oxford Street, as well as the University, Oxford Road.

Left: top, The old Town Hall

Below, Waterhouse’s Town Hall

Above: The Assize Courts.

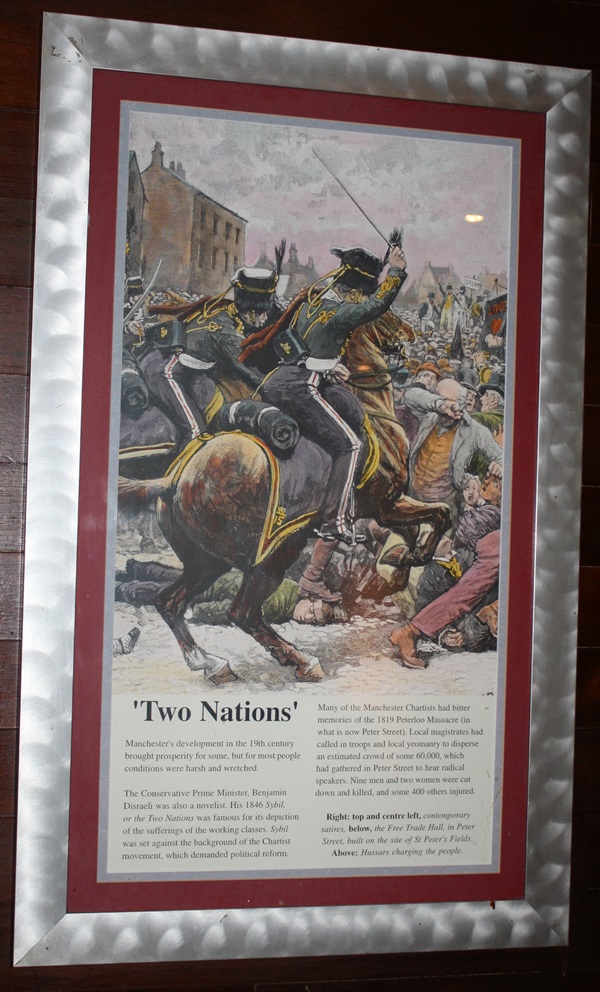

A framed drawing and text about the Peterloo massacre.

The text reads: Manchester’s development in the 19th century brought prosperity for some, but for most people conditions were harsh and wretched.

The Conservative Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli was also a novelist. His 1846 Sybil, or the Two Nations was famous for its depiction of the sufferings of the working classes. Sybil was set against the background of the Chartist movement, which demanded political reform.

Many of the Manchester Chartists had bitter memories of the 1819 Peterloo Massacre (in what is now Peter Street). Local magistrates had called in troops and local yeomanry to disperse an estimated crowd of some 60,000, which had gathered in Peter Street to hear radical speakers. Nine men and two women were cut down and killed, and some 400 others injured.

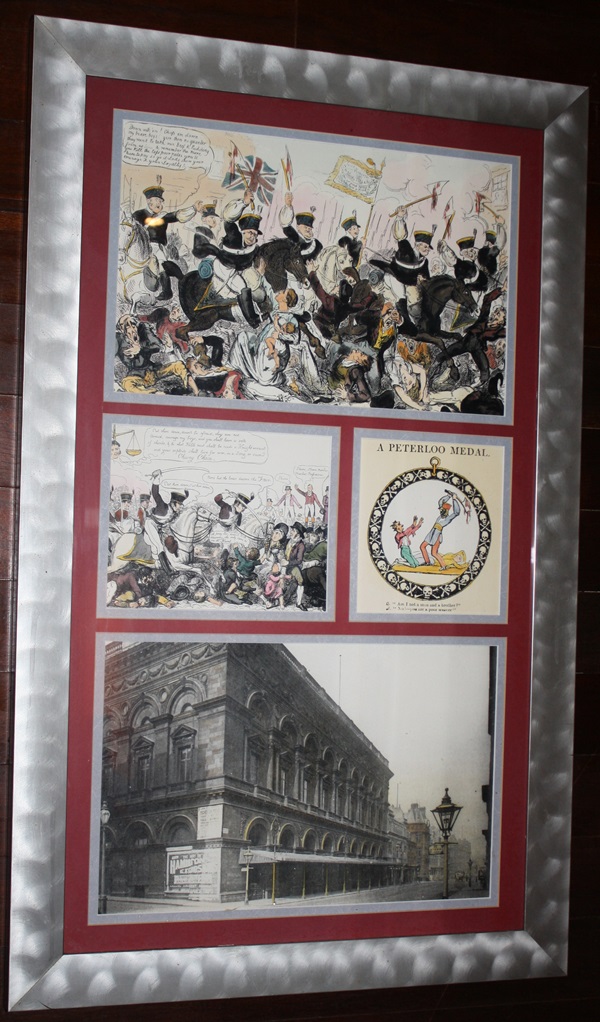

Framed drawings of troops attacking the crowds in the 1819 Peterloo massacre and a mock medal showing a troop killing a civilian. Also shown, a photograph of where the events took place, now known as Peter Street.

A view of The Picture House present day – one of the first purpose-built cinemas.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.