Pub history

The Panniers

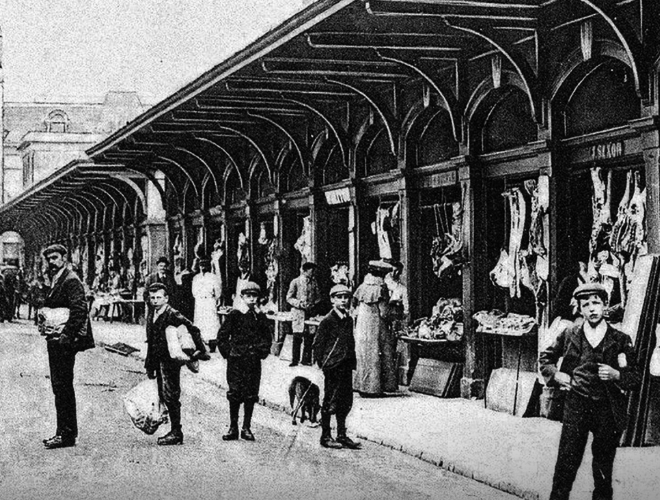

Butchers’ Row, in front of this Wetherspoon pub, once had 33 butcher’s shops on one side and the vegetable market on the other. Panniers were wicker baskets used to carry wares.

Butchers’ Row, in front of this Wetherspoon pub, once had 33 butcher’s shops on one side and the vegetable market on the other. Panniers were wicker baskets used to carry wares.

Photographs and text about The Panniers

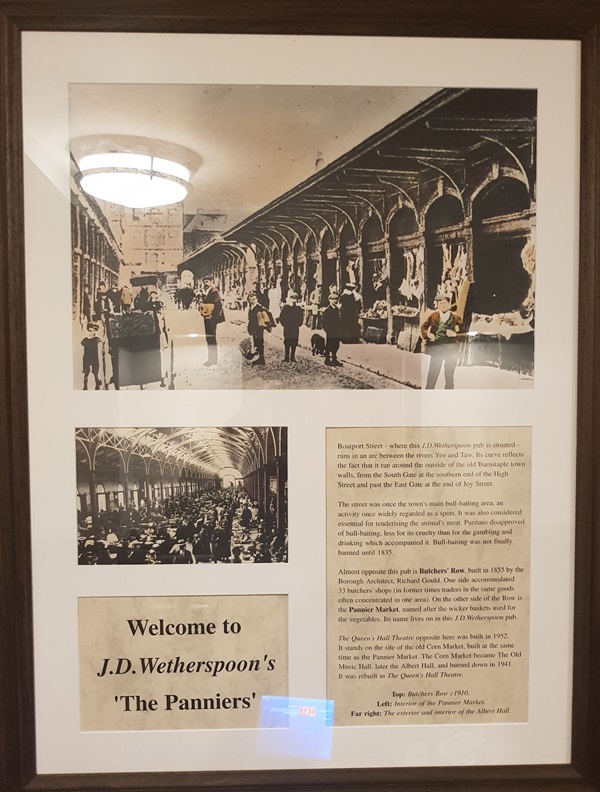

The text reads: Boutport Street – where this J D Wetherspoon pub is situated – runs in an arc between the rivers Yeo and Taw. Its curve reflects the fact that it ran around the outside of the old Barnstaple town walls, from the South Gate at the southern end of the High Street and past the East Gate at the end of Joy Street.

The street was once the town’s main bull-baiting area, an activity once widely regarded as a sport. It was also considered essential for tenderising the animal’s meat. Puritans disapproved of bull-baiting, less for its cruelty than for the gambling and drinking which accompanied it. Bull-baiting was not finally banned until 1835.

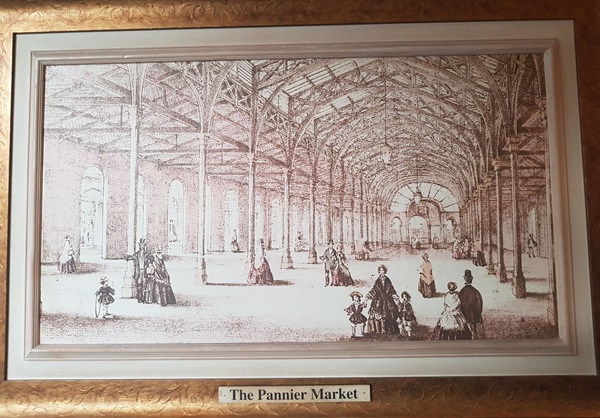

Almost opposite this pub is Butchers’ Row, built in 1855 by the Borough Architect Richard Gould. One side accommodated 33 butchers’ shops (in former times, traders in the same goods were often concentrated in one area). On the other side of the Row is the Pannier Market, named after the wicker baskets used for the vegetables. Its name lives on in this J D Wetherspoon pub.

The Queen’s Hall Theatre opposite here was built in 1952. It stands on the site of the old Corn Market, built at the same time as the Pannier Market. The Corn Market became The Old Music Hall, later the Albert Hall, and burned down in 1941. It was rebuilt as The Queen’s Hall Theatre.

Top: Butchers Row, c1910

Left: Interior of the Pannier Market

Far right: The exterior and interior of the Albert Hall

Illustrations and text about pewter-making

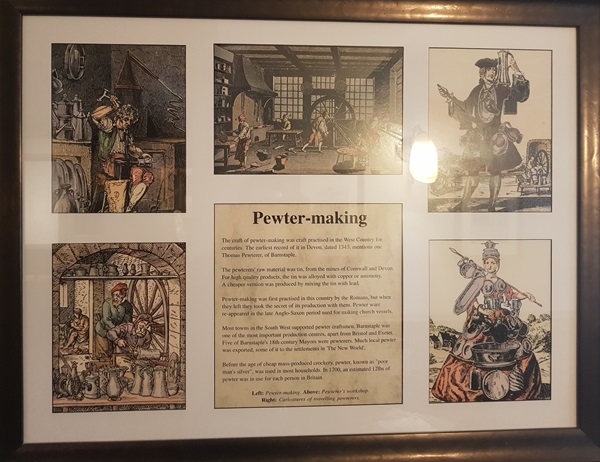

The text reads: The craft of pewter-making was a craft practised in the West Country for centuries. The earliest record of it in Devon, dated 1343, mentions one Thomas Pewterer, of Barnstaple.

The pewterers’ raw material was tin, from the mines of Cornwall and Devon. For high-quality products, the tin was alloyed with copper or antimony. A cheaper version was produced by mixing the tin with lead.

Pewter-making was first practised in this country by the Romans, but when they left, they took the secret of its production with them. Pewter ware reappeared in the late Anglo-Saxon period, used for making church vessels.

Most towns in the South West supported pewter craftsmen. Barnstaple was one of the most important production centres, apart from Bristol and Exeter. Five of Barnstaple’s 18th-century mayors were pewterers. Much local pewter was exported, some of it to the settlements in ‘The New World’.

Before the age of cheap mass-produced crockery, pewter, known as ‘poor man’s silver’, was used in most households. In 1700, an estimated 12lb of pewter was in use for each person in Britain.

Left: Pewter-making

Above: Pewterer’s workshop

Right: Caricatures of travelling pewterers

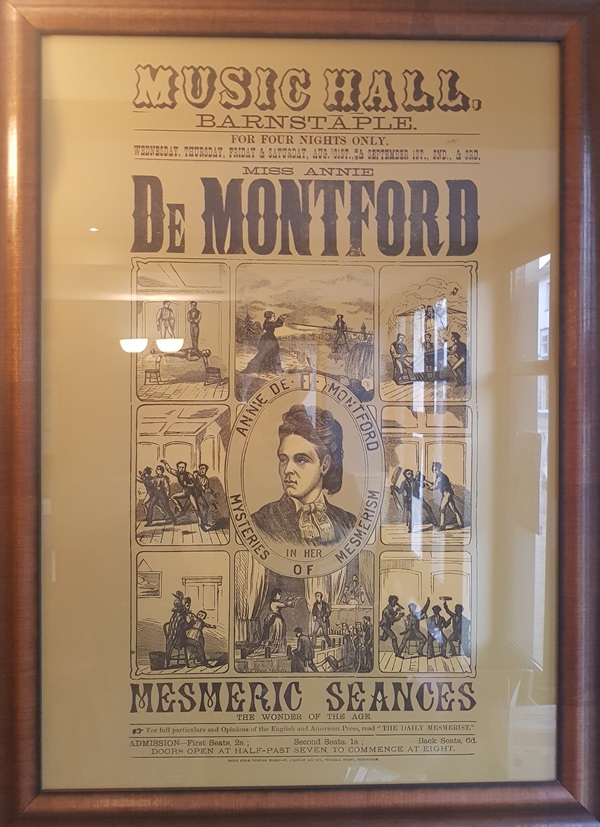

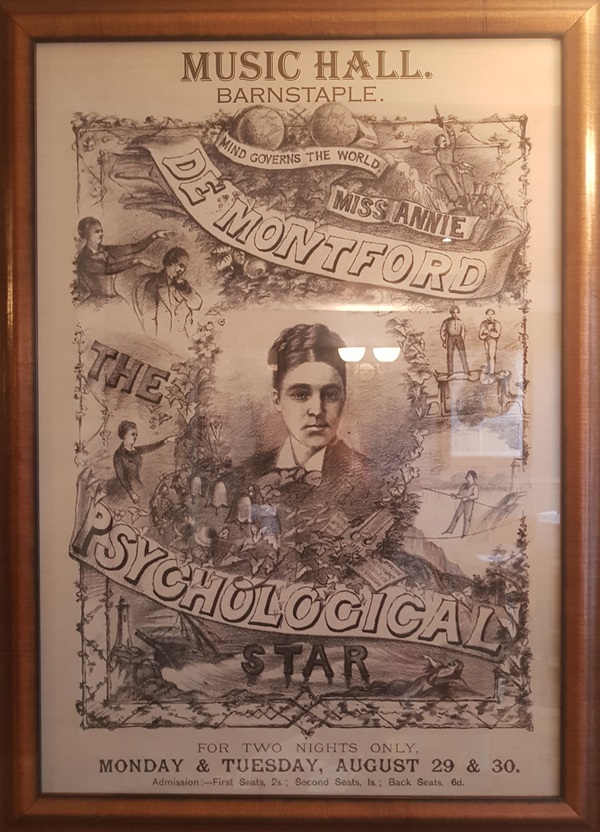

Posters advertising performances at Barnstaple Music Hall

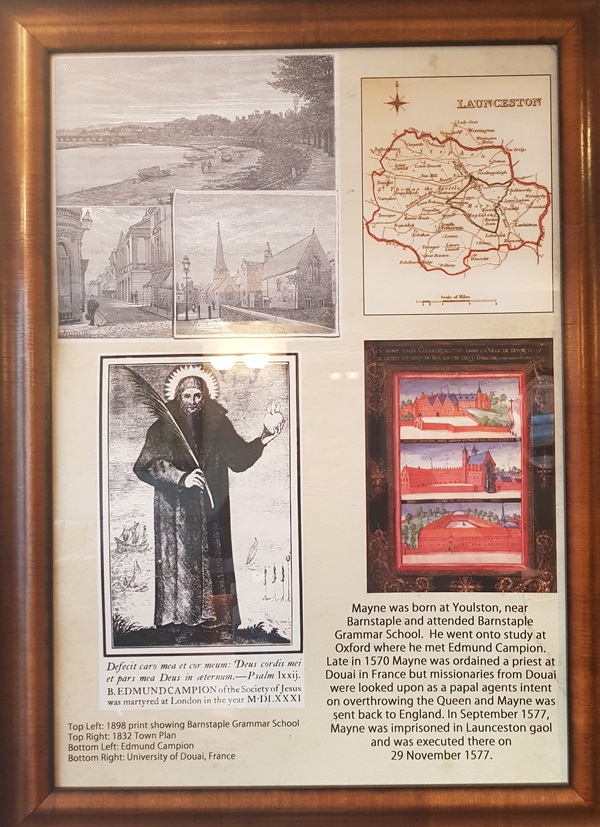

Prints and text about Mayne of Barnstaple

The text reads: Mayne was born at Youlston, near Barnstaple, and attended Barnstaple Grammar School. He went on to study at Oxford, where he met Edmund Campion. Late in 1570, Mayne was ordained a priest at Douai in France, but missionaries from Douai were looked upon as papal agents intent on overthrowing the Queen, and Mayne was sent back to England. In September 1577, Mayne was imprisoned in Launceston gaol, and he was executed there on 29 November 1577.

Top, left: 1898 print showing Barnstaple Grammar School

Top, right: 1832 Town Plan

Bottom, left: Edmund Campion

Bottom, right: University of Douai, France

Prints and text about the Civil War

The text reads: Barnstaple and most of Devon tended to the Parliamentary side when the Civil War began in 1642. However, the town accepted Royalist occupation in 1643, after the siege and surrender of Bideford. It was taken over by Prince Maurice, King Charles’ nephew. In spite of agreements, his troops then looted the town.

Maurice unwisely sent part of his army to act as escort to the Queen, whereupon the townspeople expelled the rest. However, after a siege, Barnstaple was reoccupied, plundered a second time, and refortified.

In 1645, Charles’ eldest son, later Charles II, arrived here, fleeing from an outbreak of plague in Bristol. Although aged only 15, he had been appointed general of the royal forces in the South West. He left after a few weeks for Launceston and fled into exile the following year.

Barnstaple was relieved of its Royal garrison in 1646, after the surrender of Torrington and Exeter.

Above: Satirical prints of the conflict

Right: Charles II as a youth

An illustration of the Pannier Market

Illustrations of the old Guildhall (top) and Corn Market (bottom)

Framed workman’s instruments

These framed workman’s instruments are reminiscent of the tools used by the traders of the Pannier Market. The present Pannier Market, designed by the borough surveyor Richard Davey Gould, opened in 1855 and linked High Street and Boutport Street. This was intended for vegetables, with a corn market and music hall built shortly after at the Boutport Street end. The displaced butchers were provided with the brand-new Butchers’ Row of permanent stalls.

Despite the misgivings of some townspeople, the Pannier Market, as it became known, proved to be a great success. By 1897, Gardiner, one of the town’s historians, was able to write, ‘the result is that Barnstaple can today boast of the possession of markets such as many a country town might well envy. Indeed, Barum’s Pannier Market is one of the finest in the kingdom’.

Framed workman’s instruments

These framed workman’s instruments are reminiscent of the tools used by the traders of the Pannier Market.

Since Saxon times, Barnstaple has served as a market town for the surrounding countryside. Traditionally, separate markets for meat, fish, produce and other goods were held in the streets of the town, with Friday appointed as the main market day for livestock from Queen Mary’s time. By 1672, a weekly pattern was established.

In 1826, the present Guildhall was built over the High Street end of the meat market, and after another Act of Parliament in 1852, planning began for the new Pannier Market.

External photograph of the building – main entrance