Pub history

The Moon Under Water

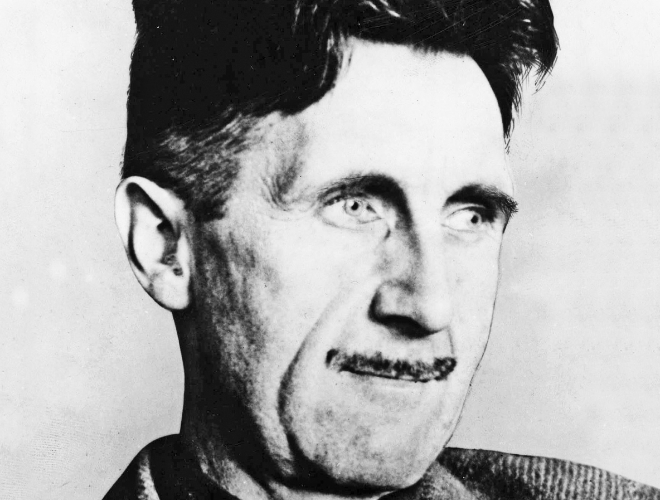

The name of this Wetherspoon free house was inspired by the ideal pub described in detail by George Orwell. The famous writer called his fictional pub ‘Moon Under Water’. These premises occupy (more or less) the site of Sorrento Villa. The Victorian villa was one of the few buildings along London Road before Norbury developed into a suburb. From the 1880s until the outbreak of World War I, it was home to the Fitchew family.

1327 London Road, Norbury, London, SW16 4AU

The

name of this Wetherspoon free house was inspired by the ideal pub described in

detail by George Orwell. The famous writer called his fictional pub ‘Moon Under Water’. These premises occupy (more or less) the site of

Sorrento Villa. The Victorian villa was one of the few buildings along London

Road before Norbury developed into a suburb. From the 1880s until the outbreak

of World War I, it was home to the Fitchew family.

Illustrations and text about charcoal burning.

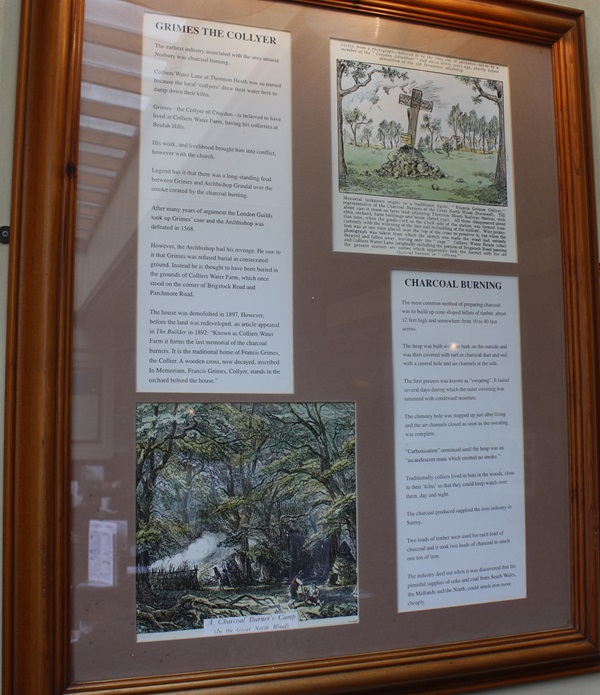

The text reads: Grimes The Collyer

The earliest industry associated with the area around Norbury was coal burning.

Colliers Water Lane at Thornton Heath was so named because the local ‘collyers’ drew their water here to damp down their kilns.

Grimes- the Collyer of Croydon- is believed to have lived at Colliers Water Farm, having his collieries at Beulah Hills.

His work, and livelihood, brought him into conflict however with the church.

Legend has it that there was a long-standing feud between Grimes and Archbishop Grindal over the smoke created by the charcoal burning.

After many years of argument the London Guilds took up Grimes’ case and the Archbishop was defeated in 1568.

However the Archbishop had his revenge. He saw to it that Grimes was refused burial in consecrated ground. Instead he is thought to have been buried in the grounds of Colliers Water Farm, which once stood on the corner of Brigstock Road and Parchmore Road.

The house was demolished in 1897. However, before the land was redeveloped, an article appeared in The Builder in 1892: “Known as Colliers Water Farm it forms the last memorial of the charcoal burners. It is the traditional home of Francis Grimes, the Collier. A wooden cross, now decayed, inscribed In Memoriam, Francis Grimes, Collyer, stands in the orchard behind the house”.

Charcoal Burning

The most common method of preparing charcoal was to build up cone-shaped billets of timber, about 12 feet high and somewhere from 10 to 40 feet across.

The heap was built with the bark on the outside and was then covered with turf or charcoal dust and soil with a central hole and air channels at the side.

The first process was known as “sweating”. It lasted several days during which the outer layer was saturated with condensed moisture.

The chimney hole was stopped up just after firing and the air channels closed as soon as the sweating was complete.

“Carbonisation” continued until the heap was an “incandescent mass which emitted no smoke”.

Traditionally colliers lived in huts in the woods, close to their ‘kilns’ so that they could keep watch over them, day and night.

The charcoal produced supplied the iron industry in Surrey.

Two loads of timber were used for each load of charcoal and it took two loads of charcoal to smelt one ton of iron.

The industry died out when it was discovered that the plentiful supplies of coke and coal from South Wales, the Midlands and the North, could smelt iron more cheaply.

Photographs and text about Samuel Coleridge Taylor.

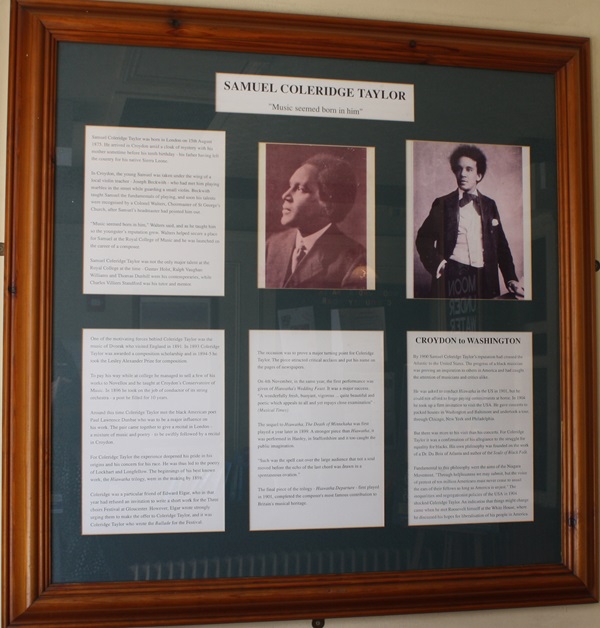

The text reads: Samuel Coleridge Taylor was born in London on 15 August 1875. He arrived in Croydon amid a cloak of mystery with his mother sometime before his tenth birthday- his father having left the country for his native Sierra Leone.

In Croydon, the young Samuel was taken under the wing of a local violin teacher- Joseph Beckwith- who had met him playing marbles in the street while guarding a small violin. Beckwith taught Samuel the fundamentals of playing, and soon his talents were recognised by a Colonel Waters, Choirmaster of St George’s Church, after Samuel’s headmaster had pointed him out.

”Music seemed born in him”, Walters said, and as he taught him so the youngster’s reputation grew. Walters helped secure a place for Samuel at the Royal College of Music and he was launched on the career of a composer.

Samuel Coleridge Taylor was not the only major talent at the Royal College at the time – Gustav Holst, Ralph Vaughn Williams and Thomas Dunhill were his contemporaries, while Charles Villiers Standford was his tutor and mentor.

One of the motivating forces behind Coleridge Taylor was the music of Dvorak who visited England in 1891. In 1893 Coleridge Taylor was awarded a composition scholarship and in 1894-5 he took the Lesley Alexander Prize for composition.

To pay his wife while at college he managed to sell a few of his works to Novellos and he taught at Croydon’s conservatoire of Music. In 1896 he took on the job of conductor of its string orchestra- a post he filled for 10 years.

Around this time Coleridge Taylor met the black American poet Paul Lawrence Dunbar who was to be a major influence on his work. The pair came together to give a recital in London- a mixture of music and poetry- to be swiftly followed by a recital in Croydon.

For Coleridge Taylor the experience deepened his pride in his origins and his concerns for his race. He was thus led to the poetry of Lockhart and Longfellow. The beginnings of his best known work, the Hiawatha trilogy, were in the making by 1898.

Coleridge was a particular friend of Edward Elgar, who in that year had refused an invitation to write a short work for the Three Choirs Festival at Gloucester. However, Elgar wrote strongly urging them to make the offer to Coleridge Taylor, and it was Coleridge Taylor who wrote the Ballade for the Festival.

The occasion was to prove a major turning point for Coleridge Taylor. The piece attracted critical acclaim and put his name on the pages of newspapers.

On 4 November, in the same year, the first performance was given of Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast. It was a major success. “A wonderfully fresh, buoyant, vigorous… quite beautiful and poetic which appeals to all and yet repays close examination”- (Musical Times).

The sequel to Hiawatha, The Death of Minnehaha was first played a year later in 1899. A stronger piece than Hiawatha, it was performed in Hanley, in Staffordshire and it too caught the public imagination.

“Such was the spell cast over the large audience that not a soul moved before the echo of the last chord was drawn in a spontaneous ovation”.

The final piece of the trilogy – Hiawatha Departure – first played in 1901, completed the composer’s most famous contribution to Britain’s musical heritage.

By 1900 Samuel Coleridge Taylor’s reputation had crossed the Atlantic to the United States. The progress of a black musician was proving an inspiration to others in America and had caught the attention of musicians and critics alike.

He was asked to conduct Hiawatha in the US in 1901, but he could not afford to forgo paying commitments at home. In 1904 he took up a firm invitation to visit the USA. He gave concerts to packed houses in Washington and Baltimore and undertook a tour, through Chicago, New York and Philadelphia.

But there was more to his visit than his concerts. For Coleridge Taylor it was a confirmation of his allegiance to the struggle for equality for all blacks. His own philosophy was founded on the work of a Dr. Du Bois of Atlanta and author of the Souls of Black Folk.

Fundamental to this philosophy were the aims of the Niagara Movement. “Through helplessness we may submit, but the voice of protest of ten million Americans must never cease to assail the ears of their fellows as long as America is unjust”. The inequalities and segregationist policies of the USA in 1904 shocked Coleridge Taylor. An indication that things must change came when he met Roosevelt himself at the White House, where he discussed his hopes for liberalisation of his people in America.

Photographs and text about Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

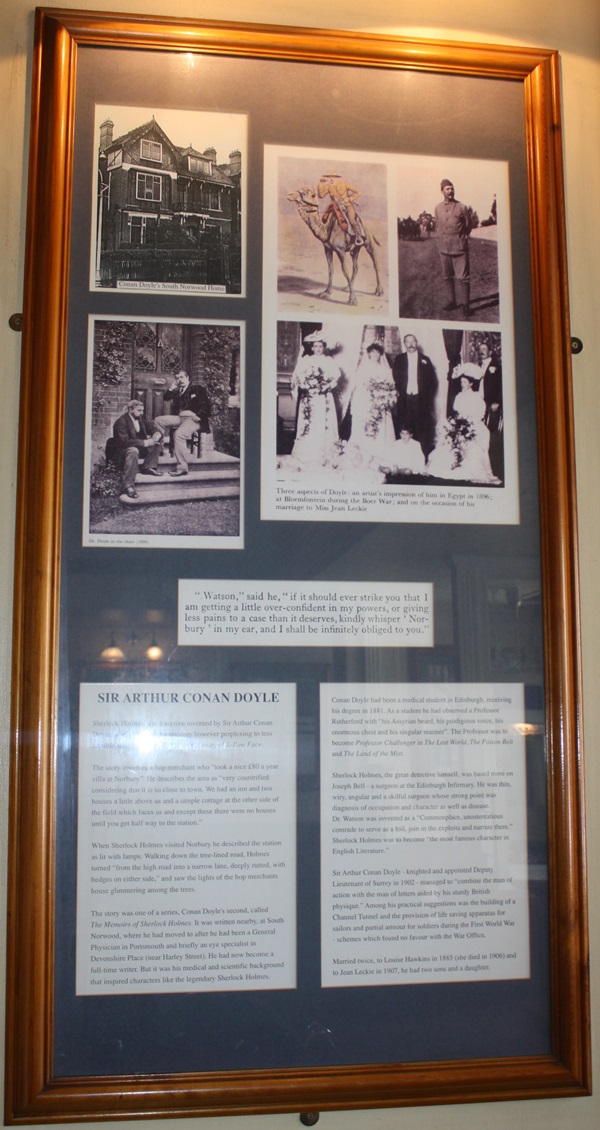

The text reads: Sherlock Holmes, the detective invented by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, always solved the mystery however perplexing to less capable sleuths except, that is, in the story of Yellow Face.

The story involves a hop merchant who “took a nice £80 a year villa at Norbury”. He describes the area as “very countrified considering that it is so close to town. We had an inn and two houses a little above us and a simple cottage at the other side of the field which faces us and except these there were no houses until you get halfway to the station”.

When Sherlock Holms visited Norbury he described the station as lit with lamps. Walking down the tree lined road, Holmes turned “from the high road into a narrow lane, deeply rutted, with hedges on either side”, and saw the lights of the hop merchants house glimmering among the trees.

The story was one of a series, Conan Doyle’s second, called The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes. It was written nearby, at South Norwood, where he had moved to after he had been a General Physician in Portsmouth and briefly an eye specialist in Devonshire Place (near Harley Street). He had now become a full-time writer. But it was his medical and scientific background that inspired characters like Sherlock Holmes.

Conan Doyle had been a medical student in Edinburgh, receiving his degree in 1881. As a student he had observed a Professor Rutherford with “his Assyrian beard, his prodigious voice, his enormous chest and his singular manner”. The professor was to become Professor Challenger in The Lost World, The Poison Belt and The Land of the Mist.

Sherlock Holmes, the great detective himself, was based more on Joseph Bell- a surgeon at the Edinburgh Infirmary. He was thin, wiry, angular and a skilful surgeon whose strongpoint was diagnosis of occupation and character as well as disease. Dr. Watson was invented as a “Commonplace, unostentatious comrade to serve as a foil, join in the exploits and narrate them”. Sherlock Holmes was to become “the most famous character in English Literature”.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle – knighted and appointed Deputy Lieutenant of Surrey in 1902 – managed to “combine the man of action with the man of letters aided by his sturdy British physique”. Among his practical suggestions was the building of a Channel Tunnel and the provision of life saving apparatus for sailors and partial armour for soldiers during the First World War- schemes which found no favour with the war office. Married twice, to Louise Hawkins in 1885 (she died in 1906) and to Jean Leckie in 1907, he had two sons and a daughter.

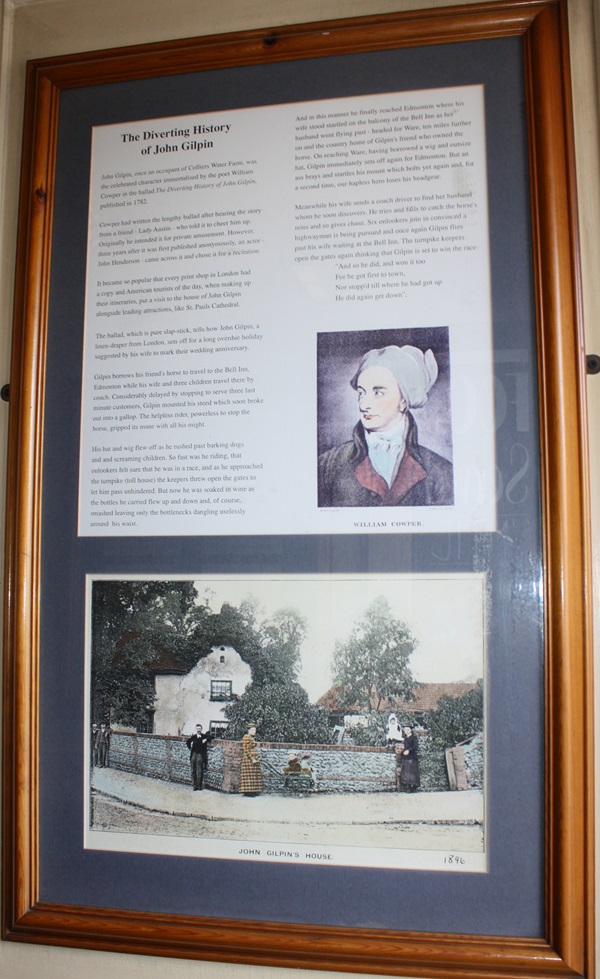

Prints and text about the history of John Gilpin.

The text reads: John Gilpin, once an occupant of Colliers Water Farm, was the celebrated character immortalised by the poet William Cowper in the ballad The Diverting History of John Gilpin, published in 1782.

Cowper had written the lengthy ballad after hearing the story from a friend – Lady Austin – who told it to cheer him up. Originally he intended it for private amusement. However, three years after it was first published anonymously, an actor – John Henderson – came across it and chose it for a recitation.

It became so popular that every print shop in London had a copy and American tourists of the day, when making up their itineraries, put a visit to the house of John Gilpin alongside leading attractions, like St. Paul’s Cathedral.

The ballad, which is pure slap-stick, tells how John Gilpin, a linen-draper from London, sets off for a long overdue holiday suggested by his wife to mark their wedding anniversary.

Gilpin borrows his friend’s horse to travel to the Bell Inn, Edmonton while his wife and three children travel there by coach. Considerably delayed by stopping to serve three last minute customers, Gilpin mounted his steed which soon broke out into a gallop. The helpless rider, powerless to stop the horse, gripped its mane with all his might.

His hat and wig flew off as he rushed past barking dogs and screaming children. So fast was he riding, that onlookers felt sure that he was in a race, and as he approached the turnpike (toll house) the keepers threw open the gates to let him pass unhindered. But now he was soaked in wine as the bottles he carried flew up and down and, of course, smashed leaving only bottlenecks dangling uselessly around his waist.

And in this manner he finally reached Edmonton where his wife stood startled on the balcony of the Bell Inn as her husband went flying past- headed for Ware, ten miles further on and the country home of Gilpin’s friend who owned the horse. On reaching Ware, having borrowed a wig and outsize hat, Gilpin immediately sets off again for Edmonton. But an ass brays and startles his mount which bolts yet again and, for a second time, our hapless hero loses his headgear.

Meanwhile his wife sends a coach driver to find her husband whom he soon discovers. He tries and fails to catch the horse’s reins and so gives chase. Six onlookers join in convinced a highwayman is being pursued and once again Gilpin flies past his wife waiting at the Bell Inn. The turnpike keepers open the gates again thinking that Gilpin is set to win the race –

“And so he did, and won it too

For he got first to town,

Nor stopp’d till where he had got up

He did again get down”.

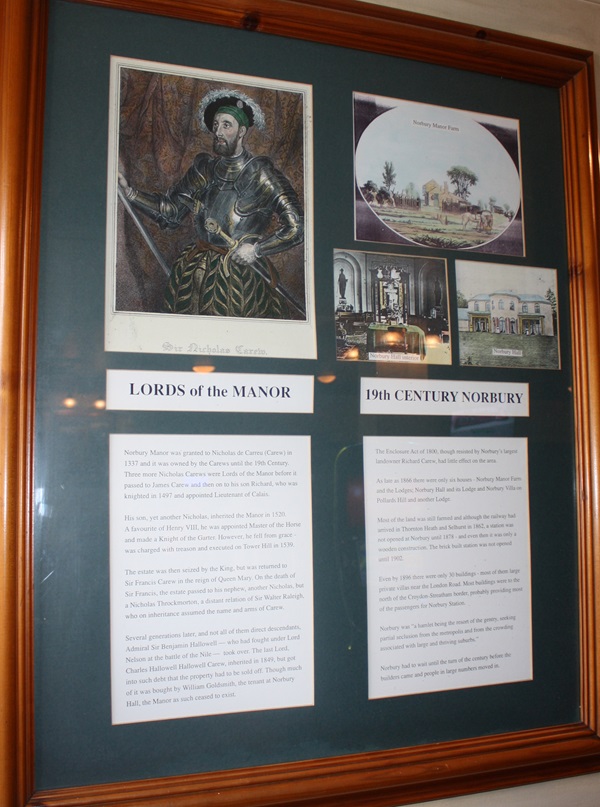

Prints and text about Lords of the Manor and Norbury in the 19th century.

The text reads: Lords of the Manor

Norbury Manor was granted to Nicholas de Carreu (Carew) in 1337 and it was owned by the Carews until the 19th century. Three more Nicholas Carews were Lords of the Manor before it passed to James Carew and then on to his son Richard, who was knighted in 1497 and appointed Lieutenant of Calais.

His son, yet another Nicholas, inherited the Manor in 1520. A favourite of Henry VII, he was appointed Master of the Horse and made a Knight of the Garter. However, he fell from grace – was charged with treason and executed on Tower Hill in 1539.

The estate was then seized by the King, but was returned to Sir Francis Carew in the reign of Queen Mary. On the death of Sir Francis, the estate passed to his nephew, another Nicholas, but a Nicholas Throckmorton, a distant relation of Sir Walter Raleigh, who on inheritance assumed the name and arms of Carew.

Several generations later, and not all of them direct descendants, Admiral Sir Benjamin Hallowell – who had fought under Lord Nelson at the battle of the Nile – took over. The last Lord Charles Hallowell Hallowell Carew, inherited in 1849, but got into such debt that the property had to be sold off. Though much of it was bought off by William Goldsmith, the tenant at Norbury Hall, the Manor as such ceased to exist.

19th Century Norbury

The Enclosure Act of 1800, though resisted by Norbury’s largest landowner Richard Carew, had little effect on the area.

As late as 1866 there were only six houses – Norbury Manor Farm and the Lodges; Norbury Hall and its Lodge and Norbury Villa on Pollards Hill and another Lodge.

Most of the land was still farmed and although the railway had arrived in Thornton Heath and Selhurst in 1862, a station was not opened at Norbury until 1878 – and even then it was only a wooden construction. The brick built station was not opened until 1902.

Even by 1896 there were only 30 buildings – most of them large private villas near the London Road. Most buildings were to the north of the Croydon-Streatham border, probably providing most of the passengers for Norbury Station.

Norbury was “a hamlet being the resort of the gentry, seeking partial seclusion from the large metropolis and from the crowding associated with large and thriving suburbs”.

Norbury had to wait until the turn of the century before the builders came and people in large numbers moved in.

Prints and text about the Great Fraud Scandal.

The text reads: Croydon’s Mayor from 1887-89 was one James W Hobbs. He lived in Norbury Hall, which had replaced the original Manor House.

A great cricket enthusiast, he held lavish garden parties in the grounds to entertain visiting teams and watch them play his own team.

The area’s largest employer, Hobbs was a director of the Croydon Tramways. He owned the Greyhound Hotel and the Steam Sawmill in Morland Road.

He had huge building operations and was contractor to Jabez Spencer Balfour, Croydon’s first mayor, and was involved in building some of London’s landmarks – Hyde Park Court, Whitehall Court, Carlisle Mansions and Cecil Hotel.

Much of Worthing on the south coast was built by his workers and he was, for ‘services rendered’ elected to Worthing Town Council.

His world fell apart when in 1892, he was arrested, convicted of fraud and sentenced to 12 years imprisonment for his part in the Liberator Building Society Scandal when, along with Balfour and others, thousands of pounds of Croydon’s money was misappropriated.

He came back, however, to develop Norbury in partnership with his brothers- operating as Hobbs & Co.

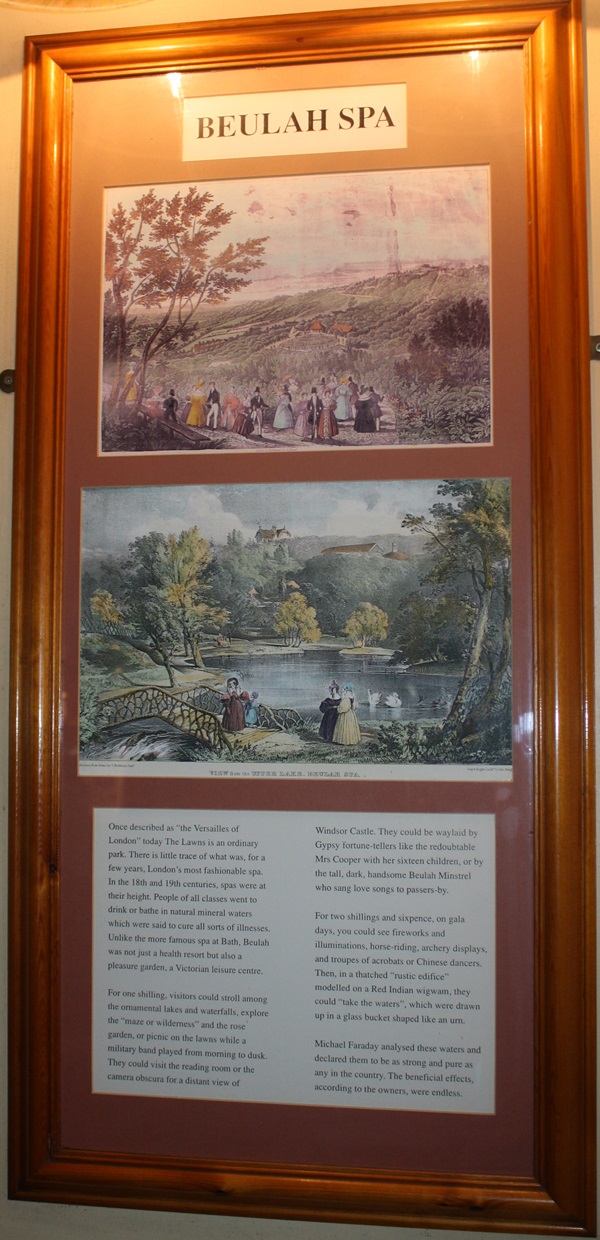

Illustrations and text about Beulah Spa.

The text reads: Once described as “the Versailles of London” today The Lawns is an ordinary park. There is little trace of what was, for a few years, London’s most fashionable spa. In the 18th and 19th centuries, spas were at their height. People of all classes went to drink or bathe in natural mineral waters which were said to cure all sorts of all illnesses. Unlike the more famous spa at Bath, Beulah was not just a health resort but also a pleasure garden, a Victorian leisure centre.

For one shilling, visitors could stroll among the ornamental lakes and waterfalls, explore the “maze of wilderness” and the rose garden, or picnic on the lawns while a military band played from morning to dusk. They could visit the reading room or the camera obscura for a distant view of Windsor Castle. They could be waylaid by Gypsy fortune-tellers like the redoubtable Mrs Cooper with her sixteen children, or by the tall, dark, handsome Beulah Minstrel who sang love songs to passers-by.

For two shillings and sixpence, on gala days, you could see fireworks and illuminations, horse-riding, archery displays, and troupes of acrobats or Chinese dancers. Then, in a thatched “rustic edifice” modelled on a Red Indian wigwam, they could “take the waters”, which were drawn up in a glass bucket shaped like an urn.

Michael Faraday analysed these waters and declared them to be as strong and pure as any in the country. The beneficial effects, according to the owners, were endless.

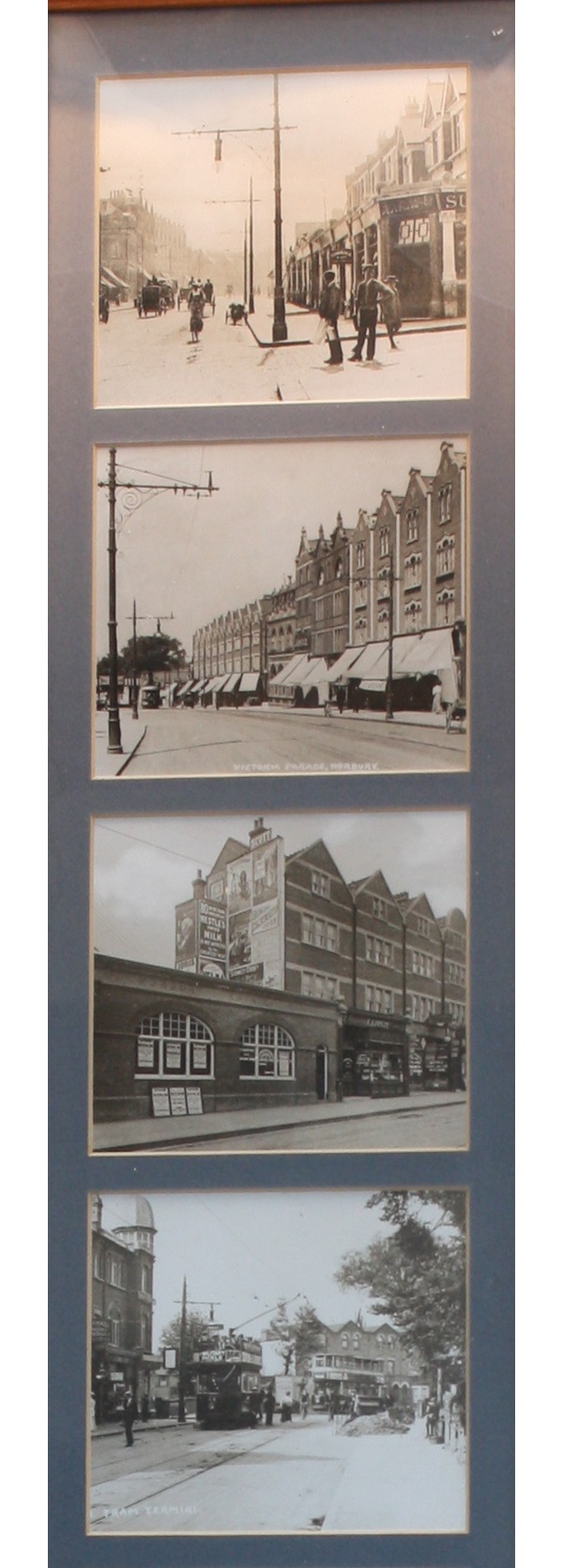

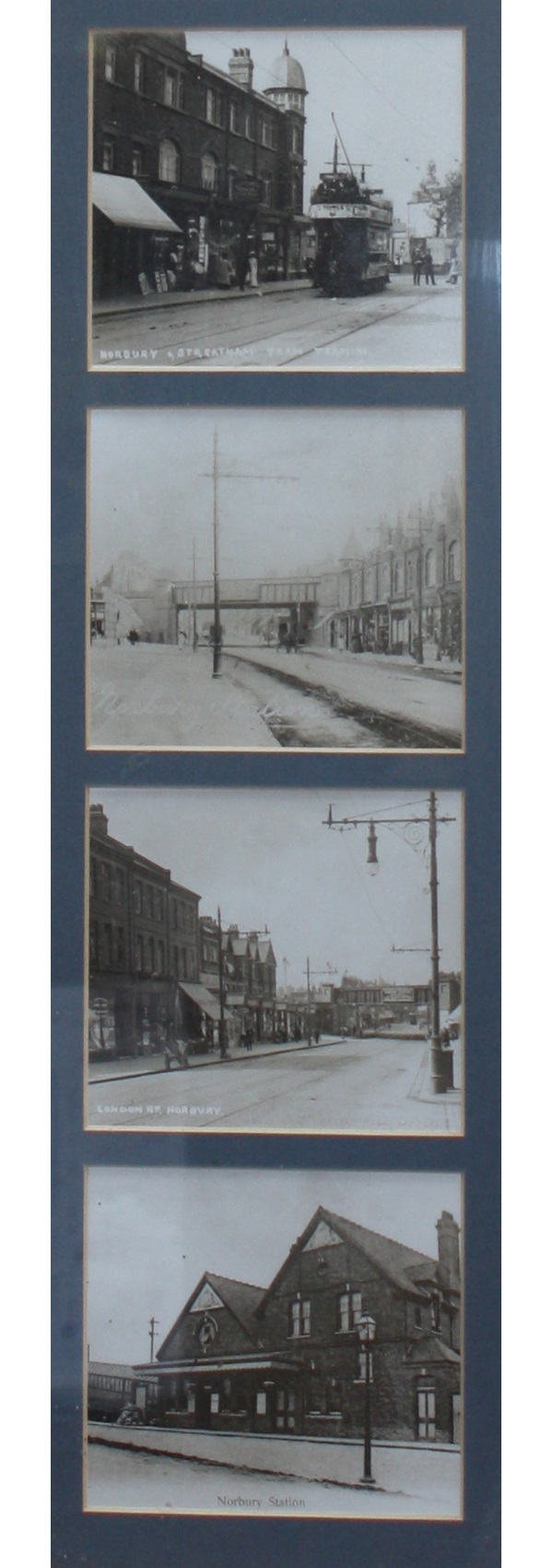

Old photographs of Norbury.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.