Pub history

The Moon and Stars

The famous writer George Orwell described his ideal pub in detail in a newspaper article. He named his fictional pub ‘Moon Under Water’ which is why ‘moon’ appears in the name of several Wetherspoon pubs. This pub opened in 1994, in premises previously occupied by Bonbon, Ladies’ Fashions (99 South Street) and Pizza Hut (101–103). The building was erected in the inter-war years on the site of a detached Victorian house and its walled garden.

99–103 South Street, Romford, London, RM1 1NX

The famous writer George Orwell described his favourite pub in detail in newspaper article. He named his fictional pub ‘Moon Under Water’ which is why ‘moon’ appears in the name of several Wetherspoon pubs. This pub opened in 1994, in premises previously occupied by Bonbon, Ladies’ Fashions (99 South Street) and Pizza Hut (101–103). The building was erected in the inter-war years on the site of a detached Victorian house and its walled garden.

Prints and text about Elizabeth I.

The text reads: During her forty-five-year long reign Elizabeth often uprooted her court, taking her courtiers on ‘royal progresses’ around the country. The Queen and her entourage passed along the Great Wessex Road, through Romford, on several occasions.

Nearby Havering Palace, was the overnight resting point at the end of the first day’s travel from London. Elizabeth made a total of nine royal progresses through Essex, which were undertaken in the summer months.

The Queen often rode on horseback so that she could be seen more easily by her subjects. Robert Dudley, Master of the Horse, rode closeby. The royal retinue followed, with dozens of carts bringing all the necessary provisions.

Above: The Great Seal of Elizabeth I, showing her on horseback

Right: above, Elizabeth I in 1592, painted to commemorate her visit to Sir Henry Lee, her champion at the Tilt, below, Elizabeth dancing with her favourite Sir Robert Dudley.

Illustrations and text about roads and transport in Romford.

The text reads: Romford is located on the old Roman Road linking London and Colchester. The invaders built a posting station in the area, known as Durolitum. It is listed in the famous second century ‘Antonione Directory’, as being 15 miles from London.

Centuries later, the London-Colchester highway was improved by the Turnpike Trust and became a major coaching route. Romford prospered. Up to forty coaches a day stopped at the town’s inn, several of which had large stables.

The coaching age lasted until the arrival of the railways. Romford station opened in South Street, (near these premises) in 1839. By the 1930s South Street had become Romford’s ‘Golden Mile’, full of shops and places of entertainment.

Above: Loading up a coach at a country inn by Hogarth, 1747

Right: above, from ‘Old Coaching Days’, a heavy load struggling on a bad road, below, stage coach travellers breakfasting before the day’s journey.

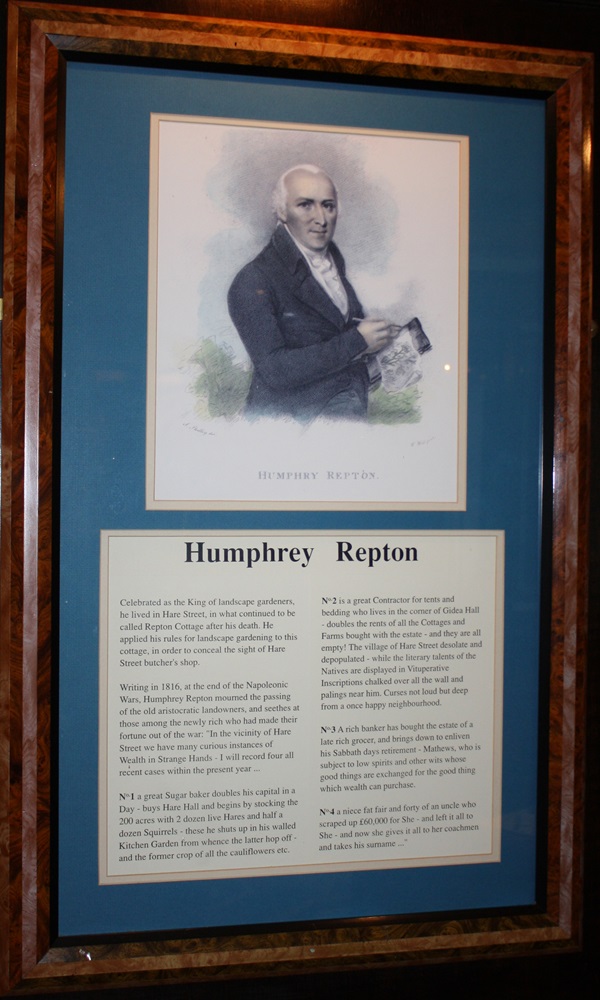

An illustration and text about Humphrey Repton.

The text reads: Celebrated as the King of landscape gardeners, he lived in Hare Street, in what continued to be called Repton Cottage after his death. He applied his rules for landscape gardening to this cottage, in order to conceal the sight of Hare Street butcher’s shop.

Writing in 1816, at the end of the Napoleonic Wars, Humprey Repton mourned the passing of the old aristocratic landowners, and seethes at those among the newly rich who had made their fortune out of the war: “In the vicinity of Hare Street we have many curious instances of Wealth in Strange Hands – I will record four all recent cases within the present year….

No. 1 a great Sugar baker doubles his capital in a day – buys Hare Hall and begins by stocking the 200 acres with 2 dozen live Hares and half a dozen Squirrels – these he shuts up in his walled Kitchen Garden from whence the latter hop off – and the former crop of all the cauliflowers etc.

No. 2 is a great Contractor for tents and bedding who lives in the corner of Gidea Hall – doubles the rents of all the Cottages and Farms bought with the estate – and they are all empty! The village of Hare Street desolate and depopulated – while the literary talents of the Natives are displayed in Vituperative Inscriptions chalked over all the wall and palings near him. Curses not loud but deep from a once happy neighbourhood.

No. 3 a rich banker has bought the estate of a late rich grocer, and brings down to enliven his Sabbath days retirement – Mathews, who is subject to low spirits and other wits who good things are exchanged for the good thing which wealth can purchase.

No. 4 a niece fat fair and forty of an unle who scarped up £60,000 for She – and left it all to She – and now she gives it all to her coachmen and takes him surname…”

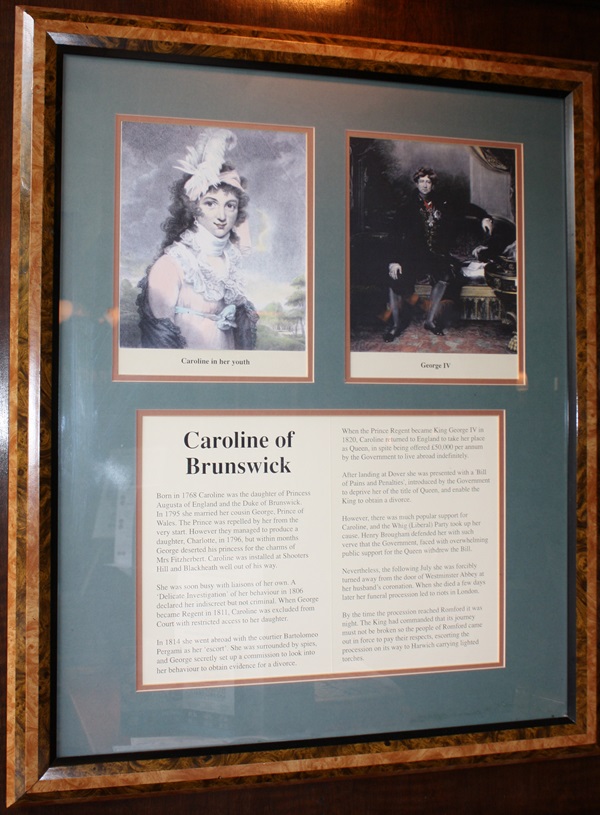

Prints and text about Caroline of Brunswick.

The text reads: Born in 1768 Caroline was the daughter of Princess Augusta of England and the Duke of Brunswick. In 1795 she married her cousin George, Prince of Wales. The Prince was repelled by her from the very start. However, they managed to produce a daughter, Charlotte, in 1796, but within months George deserted his princess for the charms of Mrs Fitzherbert. Caroline was installed at Shooters Hills and Blackheath well out of his way.

She was soon busy with liaisons of her own. A ‘Delicate Investigation’ of her behaviour in 1806 declared her indiscreet but not criminal. When George became Regent in 1811, Caroline was excluded from Court with restricted access to her daughter.

In 1814 she went abroad with the courtier Bartolomeo Pergami as her ‘escort’. She was surrounded by spies, and George secretly set up a commission to look into her behaviour to obtain evidence for a divorce.

When the Prince Regent became King George IV in 1820, Caroline returned to England to take her place as Queen, in spite of being offered £50,000 per annum by the Government to live abroad indefinitely.

After landing at Dover she was presented with a ‘Bill of Pains and Penalties’, introduced by the Government to deprive her of the title of Queen, and enable the King to obtain a divorce.

However, there was much popular support for Caroline, and the Whig (Liberal) Party took up her cause. Henry Brougham defended her with such verve that the Government, faced with overwhelming public support for the Queen withdrew the Bill.

Nevertheless, the following July she was forcibly turned away from the door of Westminster Abbey at her husband’s coronation. When she died a few days later her funeral procession led to riots in London.

By the time the procession reached Romford it was night. The King had commanded that its journey must not be broken so the people of Romford came out in force to pay their respects, escorting the procession on its way to Harwich carrying lighted torches.

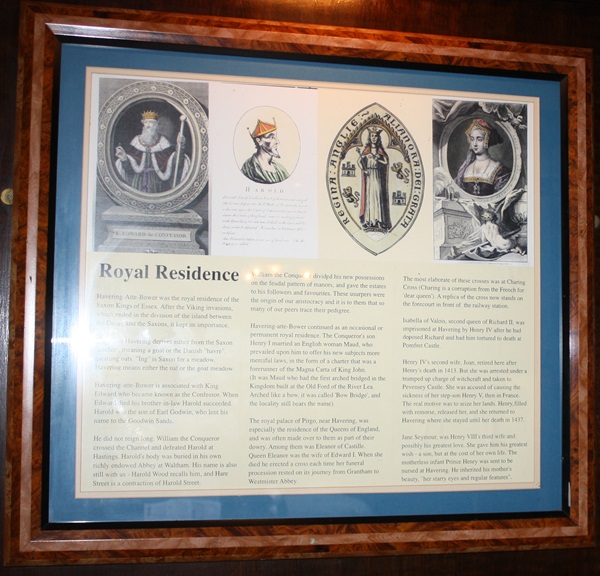

Prints and text about royalty in the area.

The text reads: Havering-Atte-Bower was the royal residence of the Saxon Kings of Essex. After the Viking invasions, which ended in the division of the island between the Danes and the Saxons, it kept its importance.

The name Havering dervies either from the Saxon”haefer”, meaning a goat or the Danish “havre”, meaning oats. “Ing” is Saxon for a meadow. Havering means either the oat or the goat meadow.

Havering-Atte-Bower is associated with King Edward who became known as the Confessor. When Edward died his brother-in-law Harold succeeded. Harold was the son of Earl Godwin, who lent his name to the Goodwin Sands.

He did not reign long. William the Conqueror crossed the channel and defeated Harold at Hastings. Harold’s body was buried in his own richly endowed Abbey at Waltham. His name is also still with us – Harold Wood recalls him, and Hare Street is a contraction of Harold Street.

William the Conqueror divided his new possessions on the feudal pattern of manors, and gave the estates to his followers and favourites. These usurpers were the origin of our aristocracy and it is to them that so many of our peers trace their pedigree.

Havering-Atte-Bower continued as an occasional or permanent royal residence. The Conqueror’s son Henry I married an English woman Maud, who prevailed upon him to offer his new subjects more merciful laws, in the form of a charter that was a forerunner of the Magna Carter of King John. (It was Maud who had the first arched bridged in the Kingdom built at the Old Ford of the River Lea. Arched like a bow, it was called ‘Bow Bridge’, and the locality still bears the name).

The royal palace of Pirgo, near Havering, was especially the residence of the Queens of England, and was often made over to them as part of their dowry. Among them was Eleanor of Castille. Queen Eleanor was the wife of Edward I. When she died he erected a cross each time her funeral procession rested on its journey from Grantham to Westminster Abbey.

The most elaborate of these crosses was at Charing Cross (Charing is a corruption from the French for ‘dear queen’). A replica of the cross now stands on the forecourt in front of the railway station.

Isabella of Valois, second queen of Richard II, was imprisoned at Havering by Henry IV after he had deposed Richard and had him tortured to death at Pomfret Castle.

Henry IV’s second wife, Joan, retired here after Henry’s death in 1413. But she was arrested under a trumped up charge of witchcraft and taken to Pevensey Castle. She was accused of causing the sickness of her step-son Henry V, then in France. The real motive was to seize her lands. Henry, filled with remorse, released her, and she returned to havering where she stayed until her death in 1437.

Jane Seymour was Henry VIII’s third wife and possibly his greatest love. She gave him his greatest wish – a son, but at the cost of her own life. The motherless infant Prince henry was sent to be nursed at Havering. He inherited this mother’s beauty, “her starry eyes and regular features”.

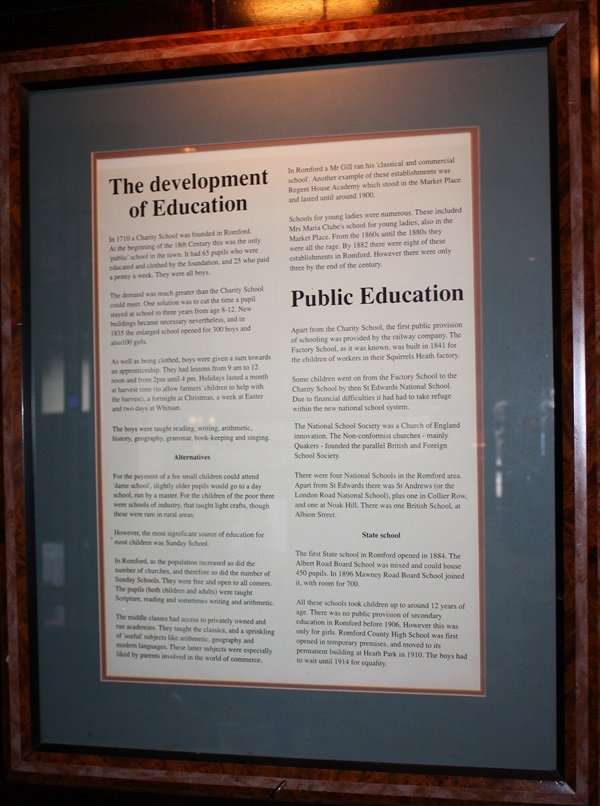

Text about education in the area.

The text reads: In 1710 a Charity School was founded in Romford. At the beginning of the 18th Century this was the only ‘public’ school in the town. It had 65 pupils who were educated and clothed by the foundation, and 25 who paid a penny a week. They were all boys.

The demand was much greater than the Charity School could meet. One solution was to cut the time a pupil stayed at school to three years from age 8-12. New buildings became necessary nevertheless, and in 1835 the enlarged school opened for 300 boys and also 100 girls.

As well as being clothed, boys were given a sum towards an apprentiship. They had lessons from 9am to 12 noon and from 2pm until 4pm. Holidays lasted a month at harvest times (to allow farmers’ children to help with the harvest), a fortnight at Christmas, a week at Easter and two days at Whitsun.

The boys were taught reading, writing, arithmetic, history, geography, grammar, book-keeping and singing.

For the payment of a fee small children could attend ‘dame school’, slightly older pupils would go to a day school, run by a master. For the children of the poor there were schools of industry, that taught light crafts, though these were rare in rural areas.

However, the most significant source of education for most children was Sunday School.

In Romford, as the population increased so did the number of churches, and therefore so did the number of Sunday Schools. They were free and open to all comers. The pupils (both children and adults) were taught Scripture, reading and sometimes writing and arithmetic.

The middle classes had access to privately owned and run academies. They taught the classics, and a sprinkling of ‘useful’ subjects like arithmetic, geography and modern languages. These latter subjects were especially liked by parents involved in the world of commerce.

In Romford a Mr Gill ran his ‘classcial and commercial school’. Another example of these establishments was Regent House Academy which stood in the Market Place and lasted until around 1900.

Schools for young ladies were numerous. These included Mrs Maria Clube’s school for young ladies, also in the Market Place. From the 1860s until the 1880s they were all the rage. By 1882 there were eight of these establishments in Romford. However there were only three by the end of the century.

Apart from the Charity School, the first publish provision of schooling was provided by the railway company. The Factory School, as it was known, was built in 1841 for the children of workers in their Squirrels Heath factory.

Some children went on from the Factory School to the Charity School by then St Edwards National School. Due to financial; difficulties it had to take refuge within the new national school system.

The National School Society was a Church of England innovation. The Non-conformist churches – mainly Quakers – founded the parallel British and Foreign School Society.

There were four National Schools in the Romford area. Apart from St Edwards there was St Andrews (or the London Road National School), plus one in Collier Row, and one at Noak Hill. There was one British School, at Albion Street.

The first State school in Romford opened in 1884. The Albert Road Board School was mixed and could house 450 pupils. In 1896 Mawney Road Board School joined it, with room 700.

All these schools took children up to around 12 years of age. There was no public provision of secondary education in Romford before 1906. However this was only for girls. Romford County High School was first opened in temporary premises, and moved to its permanent building at Heath Park in 1910. The boys had to wait until 1914 for equality.

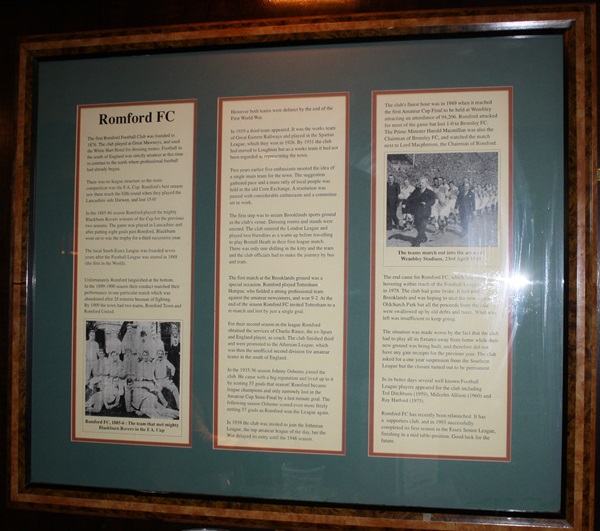

Photographs and text about Romford FC.

The text reads: The first Romford Football Club was founded in 1876. The club played at Great Mawneys, and used the White Hart Hotel for dressing rooms. Football in the south of England was strictly amateur at this time in contrast to the north where professional football had already begun.

There was no league structure so the main competition was the F.A. Cup. Romford’s best season saw them reach the fifth round when they played the Lancashire side Darwen, and lost 15.0!

In the 1885-86 season Romford played the mighty Blackburn Rovers winners of the Cup for the previous two season. The game was played in Lancashire and after putting eight goals past Romford, Blackburn went on to win the trophy for a third successive year.

The local South Essex League was founded seven years after the Football League was started in 1888 (the first in the world).

Unfortunately Romford languished at the bottom. In the 1899-1900 season their conduct matched their performance in one particular match which was abandoned after 25 minutes because of fighting. 1909 the town had two teams, Romford Town and Romford United.

However, both teams were defunct by the end of the First World War.

In 1919 a third team appeared. It was the works team of Great Eastern Railways amd played in the Spartan League, which they won in 1926. The 1931 the club had moved to Loughton but as a works team it had not been regarded as representing the town.

Two years earlier five enthusiasts mooted the idea of a single main team for the town. The suggestion gathered pace and a mass rally of local people was held in the old Corn Exchange. A resolution was passed with considerable enthusiasm and a committee set to work.

The first step was to secure Brooklands sports ground as the club’s venue. Dressing rooms and stands were erected. The club entered the London League and played two friendlies as a warm up before travelling to play Bostall Heath in their first league match. There was only one shilling in the kitty and the team and the club official had to make the journey by bus and tram.

The first match at the Brooklands ground was a special occasion. Romford played Tottenham Hotspur, who fielded a strong professional team against the amateur newcomers, and won 9-2. At the end of the season Romford FC invited Tottenham to a re-match and lost by just a single goal.

For their second season in the league, Romford obtained the services of Charlie Rance, the ex-Spurs and enland player, as coach. The club finished third and were promoted to the Athenian League, which was then the unofficial second division for amateur teams in the south of England.

In the 1935-36 season Johnny Osbourne joined the club. He came with a bg reputation and lived up to it by scoring 53 goals that season! Romford became league champions and only narrowly lost in the Amateur Cup Semi-Final by a last minute goal. The following season Osbourne scored even more freely netting 57 goals as Romford won the League again.

In 1939 the club was invited to join the Isthmian League, the top amateur league of the day, but the War delayed its entry until the 1946 season.

The club’s finest hour was in 1949 when it reached the first Amateur Cup Final to be held at Wembley attracting an attendance of 94,206. Romford attacked for most of the game but lost 1-0 to Bromley FC. The Prime Minister Harold Macmillan was also the Chairman of Bromley FC, and watched the match next to Lord Macpherson, the Chairman of Romford.

The end came for Romford FC, which had been hovering within reach of the Football League, in 1978. The club had gone broke. It had sold Brooklands and was hoping to start the new season at Oldchurch Park but all the proceeds from the sale were swallowed up by old debts and taxes. What was left was insufficient to keep going.

The situation was made worse by the fact that the club had to play all its fixtures away from home while their new ground was being built, and therefore did not have any gate receipts for the previous year. The club asked for a one year suspension from the Southern League but the closure turned out to be permanent.

In its better days several well-known Football League players appeared for the club including Ted Ditchburn (1959), Malcolm Allison (1960) and Ray Harford (1975).

Romford FC has recently been relaunched. It has a supporters club, and in 1993 successfully completed its first season in the Essex Senior League, finishing in a mid-table-position. Good luck for the future.

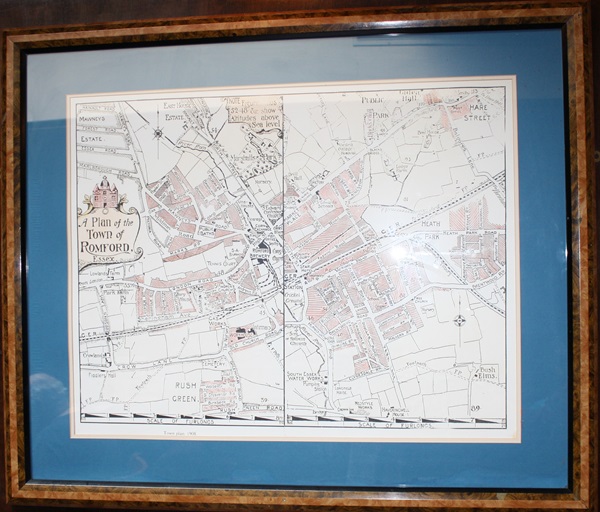

An old map of Romford.

Photographs of Romford Market.

Top: the Laurie Square end of the Market, c.1910

Above: Looking at Romford Market in the opposite direction on a non-market day, c.1895

Left: An auction sale of livestock in the 1930’s. The centre of all the attention is a Shetland pony about to be offered for sale.

A photograph of High Street, Romford.

Photographs of High Street, Romford, c1907.

A photograph of South Street, Romford, c1912.

An external view of the pub – main entrance.