Pub history

The Mary Shelley

St Peter’s churchyard contains the grave of Mary Shelley and her husband, the romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. Mary, author of the novel Frankenstein, died in London in 1851. Her body was interred in the family vault at St Peter’s by her son, Sir Percy Florence Shelley, who lived at nearby Boscombe Manor (which later became part of Bournemouth and Poole College).

St Peter’s churchyard contains the grave of Mary Shelley and her husband, the romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. Mary, author of the novel Frankenstein, died in London in 1851. Her body was interred in the family vault at St Peter’s by her son, Sir Percy Florence Shelley, who lived at nearby Boscombe Manor (which later became part of Bournemouth and Poole College).

Prints and text about The Mary Shelley

The text reads: The Shelley family have been major figures in connection with Bournemouth. The first to move here was Sir Percy Florence Shelley, the son of Mary and Percy Bysshe Shelley. Mary is best remembered as the author of Frankenstein, written at the age of just 18, and Percy was arguably the greatest of all the Romantic poets. Sir Percy Florence Shelley settled here in the undeveloped area of Boscombe in the hope that the climate would improve the health of both his mother and his wife. However, Mary died in 1851, before making the move, and came here only to be buried in the family vault in St Peter’s Church, across the road from this Wetherspoon free house.

Her husband had drowned in Italy in 1822. His body was cremated on a funeral pyre on a beach, before his remains were buried with those of their little son William in Rome. Shelley’s heart, which the flames did not consume, was taken by Leigh Hunt, who was present along with Byron for their friend’s immolation. Mary kept it by her, wrapped in silk and pages of his poem Adonais, for nearly thirty years, until it was buried with her son alongside her in the St Peter’s Church. Mary’s father – the radical thinker William Godwin – her mother – Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, author of Vindication of the Rights of Women – and her daughter-in-law are also buried at St Peter’s.

Top, left: William Godwin, Mary’s father, seated right, on trial for treason in 1794

Above, centre: Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, Mary’s mother, in 1796

Top, right: Percy Bysshe Shelley, Mary’s husband, in 1819

Right: The body of drowned Shelley being cremated, with Byron standing immediately to the left.

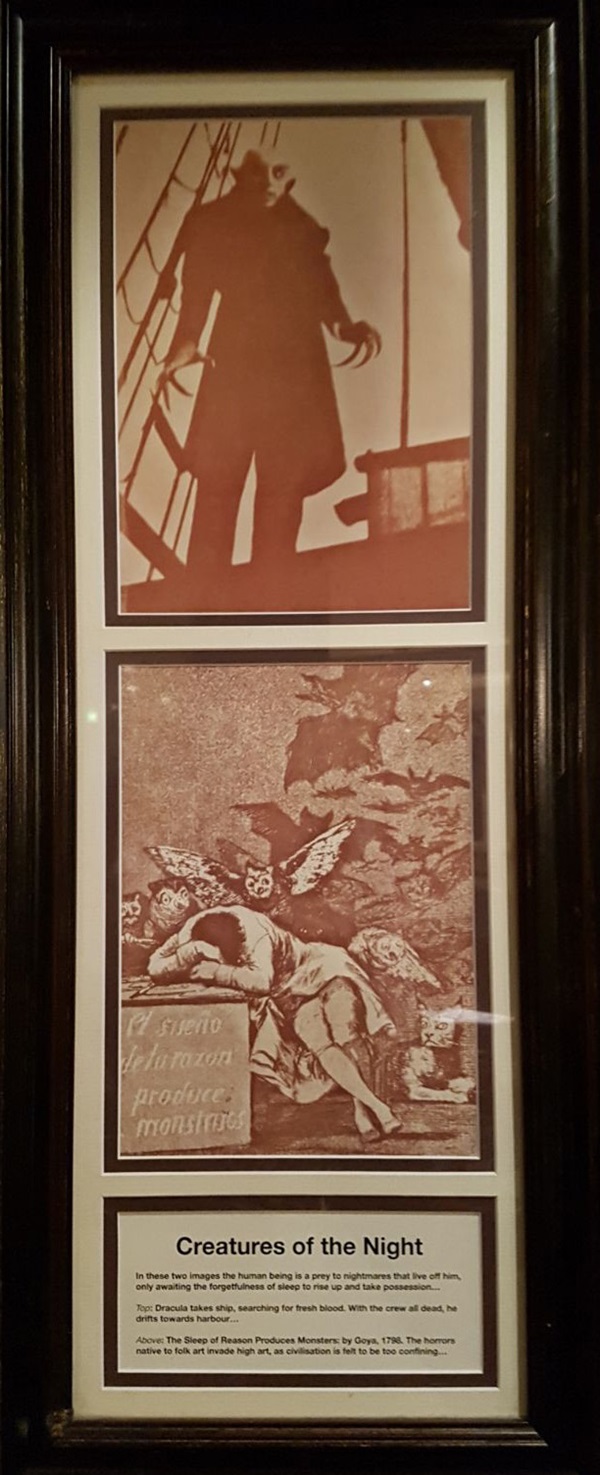

Illustrations and text about creatures of the night

The text reads: In these two images, the human being is a prey to nightmares that live off him, only awaiting the forgetfulness of sleep to rise up and take possession.

Top: Dracula takes ship, searching for fresh blood. With the crew all dead, he drifts towards harbour.

Above: The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters: by Goya, 1798. The horrors native to folk art invade high art, as civilisation is felt to be too confining.

Photographs and text about famous cases of transformation

The text reads: These two images are famous cases of transformation, where the human being, either by accident or by a disastrous decision, turns into something else.

Top: The Werewolf, bound to become a bestial murderer every full moon, doomed to kill the one he loves, and be killed by a silver bullet fired from his father’s gun.

Above: Dr Jekyll confronts ‘the horror of my other self’, the repressed public persona giving way to ‘the brute that slept within me’.

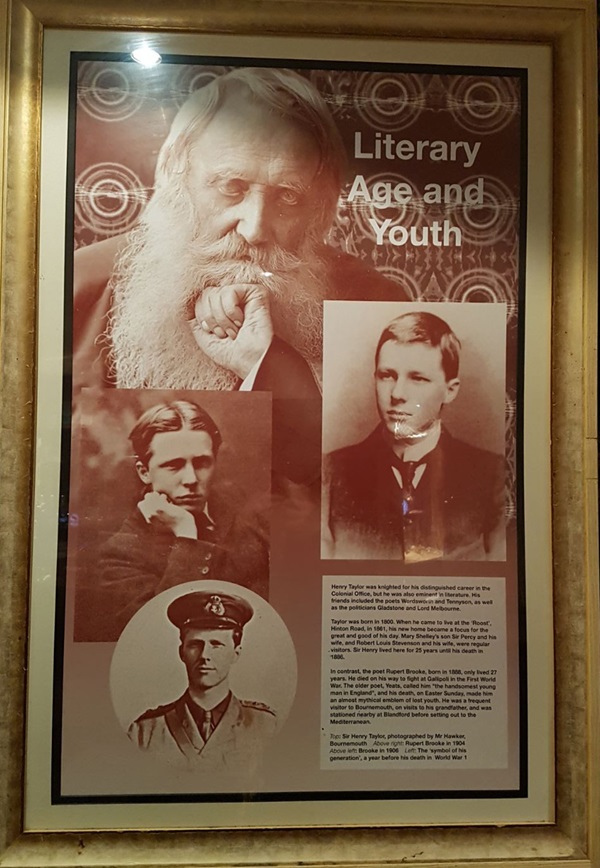

Photographs and text about Henry Taylor and Rupert Brooke

The text reads: Henry Taylor was knighted for his distinguished career in the Colonial Office, but he was also eminent in literature. His friends included the poets Wordsworth and Tennyson, as well as the politicians Gladstone and Lord Melbourne.

Taylor was born in 1800. When he came to live at the ‘Roost’, Hinton Road, in 1861, his new home became a focus for the great and good of his day. Mary Shelley’s son Sir Percy and his wife, and Robert Louis Stevenson and his wife, were regular visitors. Sir Henry lived here for 25 years until his death in 1886.

In contrast, the poet Rupert Brooke, born in 1888, lived only 27 years. He died on his way to flight at Gallipoli in the First World War. The older poet, Yeats, called him “the handsomest young man in England”, and his death, on Easter Sunday, made him an almost mythical emblem of lost youth. He was a frequent visitor to Bournemouth, on visits to his grandfather, and was stationed nearby at Blandford before setting out to the Mediterranean.

Top: Sir Henry Taylor, photographed by Mr Hawker, Bournemouth

Above, right: Rupert Brooke in 1904

Above, left: Brooke in 1906

Left: The ‘symbol of his generation’, a year before his death in World War I.

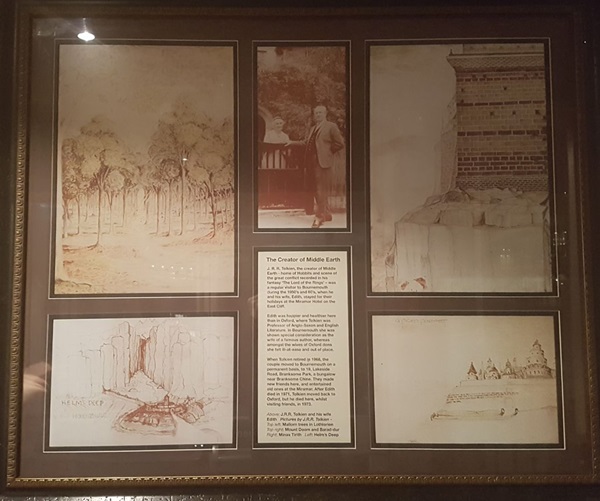

Illustrations, a photograph and text about JRR Tolkien

The text reads: JRR Tolkien, the creator of Middle Earth – home of Hobbits and scene of the great conflict recorded in his fantasy The Lord of the Rings – was a regular visitor to Bournemouth during the 1950s and 60s, when he and his wife, Edith, stayed for their holidays at the Miramar Hotel on the East Cliff.

Edith was happier and healthier here than in Oxford, where Tolkien was professor of Anglo-Saxon and English Literature. In Bournemouth she was shown special consideration as the wife of a famous author, whereas amongst the wives of Oxford dons she felt ill-at-ease and out of place.

When Tolkien retired in 1968, the couple moved to Bournemouth on a permanent basis, to 19, Lakeside Road, Branksome Park, a bungalow near Branksome Chine. They made new friends here, and entertained old ones at the Miramar. After Edith died in 1971, Tolkien moved back to Oxford, but he died here, whilst visiting friends, in 1973.

Above: JRR Tolkien and his wife Edith

Top left: Mallorn trees in Lothlorien

Top right: Mount Doom and Barad-dur

Right: Minas Tirith

Left: Helm’s Deep

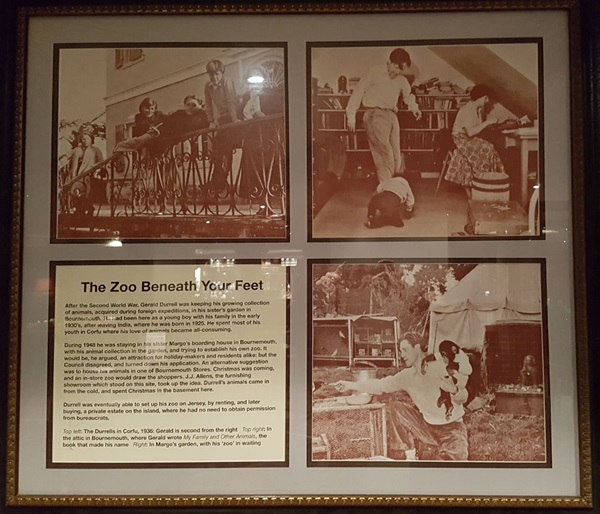

Photographs and text about Gerald Durrell

The text reads: After the Second World War, Gerald Durrell was keeping his growing collection of animals, acquired during foreign expeditions, in his sister’s garden in Bournemouth. He had been here as a young boy with his family in the early 1930s, after leaving India, where he was born in 1925. He spent most of his youth in Corfu, where his love of animals became all-consuming.

During 1948, he was staying in his sister Margo’s boarding house in Bournemouth, with his animal collection in the garden, and trying to establish his own zoo. It would be, he argued, an attraction for holiday-makers and residents alike: but the council disagreed, and turned down his application. An alternative suggestion was to house his animals in one of Bournemouth’s stores. Christmas was coming, and an in-store zoo would draw the shoppers. JJ Allen’s, the furnishing showroom which stood on this site, took up the idea. Durrell’s animals came in from the cold, and spent Christmas in the basement here.

Durrell was eventually able to set up his zoo on Jersey, by renting, and later buying, a private estate on the island, where he had no need to obtain permission from bureaucrats.

Top, left: The Durrells in Corfu, 1936; Gerald is second from the right

Top, right: In the attic in Bournemouth, where Gerald wrote My Family and Other Animals, the book that made his name

Right: In Margo’s garden, with his ‘zoo’ in waiting.

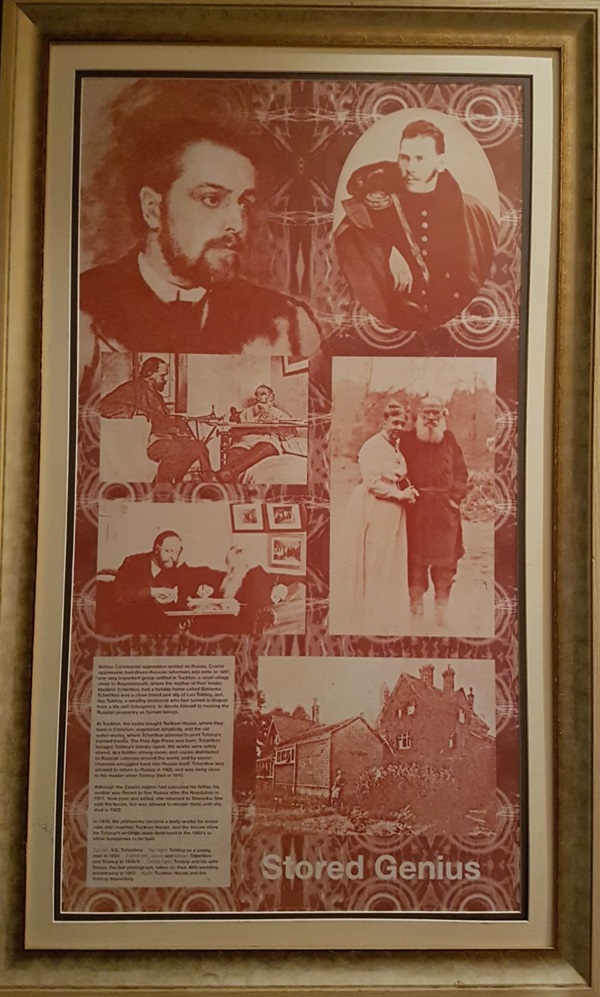

Photographs and text about Vladimir Tchertkov

The text reads: Before Communist oppression on Russia, Czarist oppression had driven Russian reformers into exile. In 1897, one very important group settled in Tuckton, a small village close to Bournemouth, where the mother of their leader Vladimir Tchertkov had a holiday home called Slavanka. Tchertkov was a close friend and ally of Leo Tolstoy, and, like Tolstoy, a wealthy aristocrat who had turned in disgust from a life self-indulgence to devote himself to treating the Russian peasantry as human beings.

At Tuckton, the exiles bought Tuckton House, where they lived in Christian, vegetarian simplicity, and the old water works, where Tchertkov planned to print Tolstoy’s banned books. The Free Age Press was born. Tchertkov became Tolstoy’s literary agent. His works were safely stored, in a hidden strong-room, and copies distributed to Russian colonies around the world, and by secret channels smuggled back into Russia itself. Tchertkov was allowed to return to Russia in 1908, and was living close to his master when Tolstoy died in 1910.

Although the Czarist regime had executed his father, his mother was forced to flee Russia after the Revolution in 1917. Now poor and exiled, she returned to Slavanka. She sold the house but was allowed to remain there until she died in 1922.

In 1918, the printworks became a bodyworks for motor cars and coaches. Tuckton House, and the secure store for Tolstoy’s writings, were destroyed in the 1960s to allow bungalows to be built.

Top, left: VG Tchertkov

Top, right: Tolstoy as a young man in 1854

Centre left, above and below: Tchertkov and Tolstoy in 1908/9

Centre, right: Tolstoy and his wife Sonya, the last photograph, taken on their 48th wedding anniversary in 1910

Right: Tuckton House and the Tolstoy depository

Photographs and text about the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra

The text reads: Dan Godfrey came from a long line of British bandmasters. As a result of a Bournemouth Council decision in 1893, he was hired to form a band which gave its first performance on Whit Monday of the same year. The contract was for six months to play three times a day to the ‘better sort’ of visitor.

Due to their popularity, most of the orchestra were retained for the winter months and became the first permanent municipal orchestra in the country. In the old Winter Gardens, Godfrey inaugurated his ‘classical concerts’ that winter. In this poor-acoustic, leaky, oversize greenhouse, Godfrey set about reviving British symphony music. By 1910, during the town’s centenary, he could call on composers to conduct their own work of the calibre of Parry, Stanford, Holst and Elgar.

Godfrey kept the orchestra going through the First World War, but the council’s determination not to subside this unique musical organisation seemed set to cut its personnel to an unviable rump. Dan Godfrey’s knighthood in 1922 saved the situation. Such national recognition made the council refrain from further reductions.

Godfrey retired in 1934, after the orchestra had moved to the Pavilion. After the war a new concert hall was built. With Charles Groves as musical director, disbandment was again threatened in 1952. The forming of the Winter Gardens Society, supported by Beecham and Barbirolli, raised funds and audience numbers, but closure loomed again in 1953, so the society took over responsibility for the orchestra from the council, renaming it the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra. A mixture of fundraising, and public and local authority support has kept this historic orchestra alive ever since.

Top and above: The Bournemouth Municipal Orchestra

Right: Sir Dan Godfrey

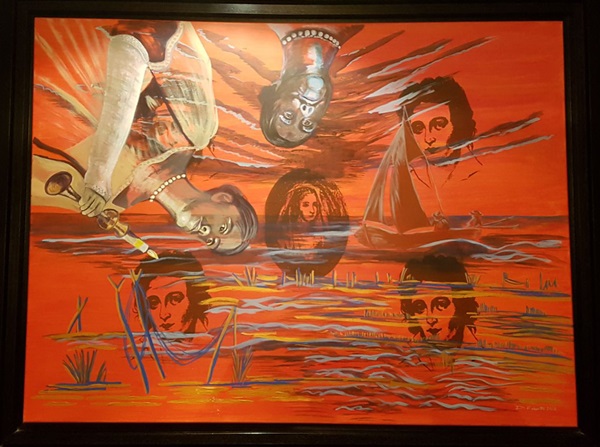

A collection of original artworks entitled The Mary Shelley Suite, by Diane Roberts

The text reads: “I use screen-printing and traditional easel painting techniques to produce what I see in my mind’s eye. Sometimes dream-like and ambiguous images emerge on which the viewer can ponder.

I have long been interested in Mary Shelley and have been influenced by her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft’s, feminist writings. I have always appreciated Shelley Manor the home of Mary’s son Percy Florence Shelley and worked in the building as a student while I was studying art.

I have visited the Shelley tomb in St Peters Church many times, and the fantastically romantic thought that Percy Bysshe Shelley’s heart was resting alongside his wife Mary was an irresistible illusion.

I approached the commission rather like an historical researcher, reading documentation and contacting local people who could explain the story in detail. Christine Azis, a local playwright, wrote the recently produced Mary Shelley Goes to Hollywood. She was a great help and gave me quotations from Mary’s journal, enabling me to fill in the personality behind the character. Mary’s early life was laced with tragedy, losing three of her four children in infancy, before a storm at sea snatched away Percy Bysshe, the love of her life.

I required the assistance of a local actress to pose in a photo shoot. Claire Hunt, a Brownsea player, fulfilled the role perfectly, and the local theatrical costume suppliers Hirearchy gave time and careful thought to the costume she was to wear. The Chaplin of St Peter’s Church gladly allowed us to visit Mary Shelley’s tomb to recreate some timely images.

Following the photo shoot I was able to select certain pictures to help me construct the artwork. Material from the internet, and the wonderful paintings by Caspar David Friedrich, offered me much inspiration, and I incorporated allusions to his powerful paintings in my compositions for the commission.

I would like to thank all those associated with the project, the Poole Printmakers for the use of their studio facilities, and the Winton Library.

External photograph of the building – main entrance