Pub history

The Liquorice Gardens

Worksop’s jewel in the crown is its priory church, where liquorice was grown in the gardens for medicinal purposes. Worksop was well known for its liquorice industry; this died out around 1750.

Worksop’s jewel in the crown is its priory church, where liquorice was grown in the gardens for medicinal purposes. Worksop was well known for its liquorice industry; this died out around 1750.

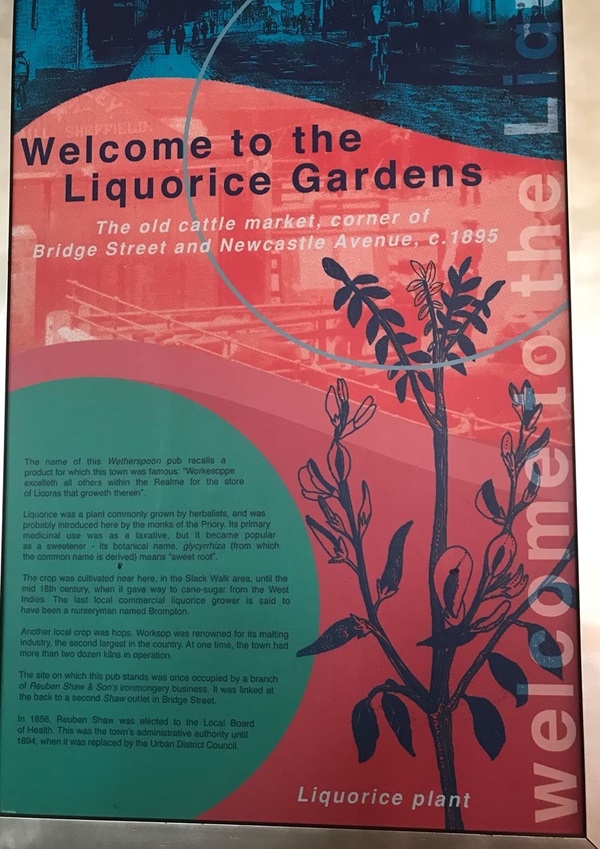

A print and text about The Liquorice Gardens

The text reads: The name of this Wetherspoon pub recalls a product for which this town was famous: “Workesoppe excelleth all others within the Realme for the store of Licoras that groweth therein.”

Liquorice was a plant commonly grown by herbalists and was probably introduced here by the monks of the priory. Its primary medicinal use was as a laxative, but it became popular as a sweetener – its botanical name, glycyrrhiza (from which the common name is derived) means ‘sweet root’.

The crop was cultivated near here, in the Slack Walk area, until the mid-18th century, when it gave way to cane sugar from the West Indies. The last local commercial liquorice grower is said to have been a nurseryman named Brompton.

Another local crop was hops. Worksop was renowned for its malting industry, the second largest in the country. At one time, the town had more than two dozen kilns in operation.

The site on which this pub stands was once occupied by a branch of Reuben Shaw & Son’s ironmongery business. It was linked at the back to a second Shaw outlet in Bridge Street.

In 1856, Reuben Shaw was elected to the Local Board of Health. This was the town’s administrative authority until 1894, when it was replaced by the Urban District Council.

Text about the Wesleyan chapel

The text reads: Opposite this Wetherspoon pub stands the Wesleyan chapel. This was built to replace an earlier structure, dating from 1863, which burnt down a century later.

The Methodist movement began with the work of John Wesley, an itinerant preacher. When he came here to speak in Worksop in 1780, he was pelted with ‘sheep’s garbage’.

The Wesleyans’ first chapel, built in 1813, stood where Newcastle Street now meets Bridge Street. The Methodists intended to rebuild there, but were paid £100 to move by the 5th Duke of Newcastle.

This enabled the Duke to extend his father’s work in straightening what is now Newcastle Avenue, thereby opening an approach to the Priory Church. The work was only completed in 1928, when King George V opened Memorial Avenue.

In 1908, a crowd gathered in the Market Place to hear the founder of the Salvation Army, General William Booth, who was then nearly 80 years old. Originally a Methodist minister, Booth felt called to take direct action to relieve poverty and hunger. He set up his ‘Christian Mission’ in London’s East End in 1865, explaining his aims in his book In Darkest England.

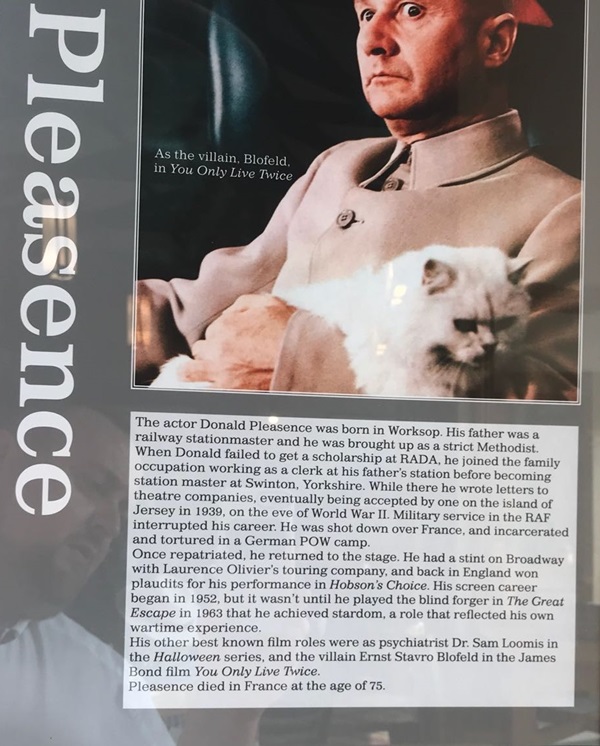

A photograph and text about Donald Pleasence

The text reads: The actor Donald Pleasance was born in Worksop. His father was a railway stationmaster, and he was brought up as a strict Methodist. When Donald failed to get a scholarship at RADA, he joined the family occupation working as a clerk at his father’s station before becoming station master at Swinton, Yorkshire. While there, he wrote letters to theatre companies, eventually being accepted by one on the island of Jersey in 1939, on the eve of World War II. Military service in the RAF interrupted his career. He was shot down over France, and incarcerated and tortured in a German POW camp.

Once repatriated, he returned to the stage. He had a stint on Broadway with Laurence Olivier’s touring company, and back in England won plaudits for his performance in Hobson’s Choice. His screen career began in 1952, but it wasn’t until he played the blind forger in The Great Escape in 1963 that he achieved stardom, a role that reflected his own wartime experience.

His other best-known film roles were as psychiatrist Dr Sam Loomis in the Halloween series, and the villain Ernst Stavro Blofeld in the James Bond film You Only Live Twice. Pleasence died in France at the age of 75.

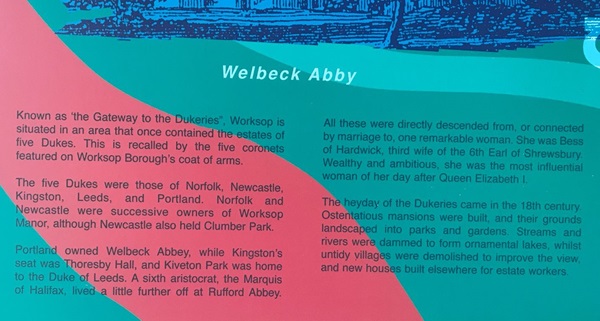

Text about Welbeck Abbey

The text reads: Known as ‘the Gateway to the Dukeries’, Worksop is situated in an area that once contained the estates of five dukes. This is recalled by the five coronets featured on Worksop Borough’s coat of arms.

The five dukes were those of Norfolk, Newcastle, Kingston, Leeds, and Portland. Norfolk and Newcastle were successive owners of Worksop Manor, although Newcastle also held Clumber Park.

Portland owned Welbeck Abbey, while Kingston’s seat was Thoresby Hall, and Kiveton Park was home to the Duke of Leeds. A sixth aristocrat, the Marquis of Halifax, lived a little further off at Rufford Abbey.

All these were directly descended from, or connected by marriage to, one remarkable woman. She was Bess of Hardwick, third wife of the 6th Earl of Shrewsbury. Wealthy and ambitious, she was the most influential woman of her day after Queen Elizabeth I.

The heyday of the Dukeries came in the 18th century. Ostentatious mansions were built, and their grounds landscaped into parks and gardens. Streams and rivers were dammed to form ornamental lakes, whilst untidy villages were demolished to improve the view and new houses built elsewhere for estate workers.

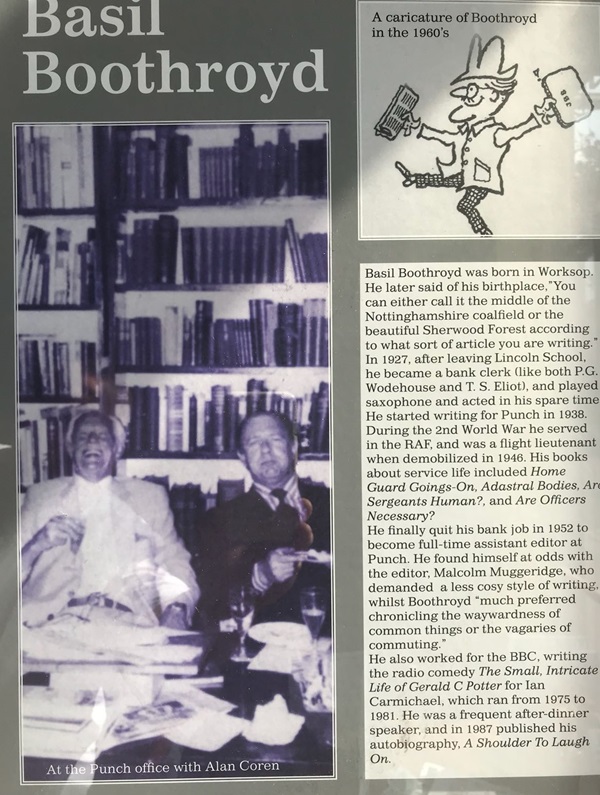

A photograph and text about Basil Boothroyd

The text reads: Basil Boothroyd was born in Worksop. He later said of his birthplace, “You can either call it in the middle of the Nottinghamshire coalfield or the beautiful Sherwood Forest according to what sort of article you are writing.”

In 1927, after leaving Lincoln School, he became a bank clerk (like both PG Wodehouse and TS Eliot), and played saxophone and acted in his spare time.

He started writing for Punch in 1938. During the 2nd World War, he served in the RAF, and was a flight lieutenant when demobilised in 1946. His books about service life included Home Guard Goings-On, Adastral Bodies, Are Sergeants Human? and Are Officers Necessary?

He finally quit his bank job in 1952 to become full-time assistant editor at Punch. He found himself at odds with the editor, Malcolm Muggeridge, who demanded a less cosy style of writing, whilst Boothroyd ‘much preferred chronicling the waywardness of common things or the vagaries of commuting’.

He also worked for the BBC, writing the radio comedy The Small, Intricate Life of Gerald C Potter for Ian Carmichael, which ran from 1975 to 1981. He was a frequent after-dinner speaker, and in 1987 published his autobiography, A Shoulder to Laugh On.

A photograph and text about Graham Taylor

The text reads: The ex-manager of the England football team, Graham Taylor, was born in Worksop in 1944. He was the son of a sports journalist and became a player, playing at full back for Grimsby Town and Lincoln City. He retired as a player through injury in 1972 and became a manager and coach. Elton John brought him to Watford, and he guided them from the Fourth Division to the First in the space of five years, achieving second place to Liverpool in 1983 and reaching the FA Cup Final in 1984.

Moving to Aston Villa, he again led his team to promotion, and a second-place finish to Liverpool in 1990, the same year that he became manager of England. He resigned in November 1993, after failing to qualify for the 1994 FIFA World Cup. He faced withering press criticism, and exposure in a documentary that filmed the failed qualifying campaign.

Back in club football, he again led Watford from bottom of the Second Division to the Premier League in two seasons. He also returned as manager of Aston Villa from 2002–03. He was chairman of Watford FC from 2009 until 2012 and works as a pundit for BBC Radio Five Live.

Text about Worksop’s finest old buildings

The text reads: Two of Worksop’s finest old buildings stand less than a half-mile east of this Wetherspoon pub. Both the Norman church of St Mary and St Cuthbert and the 14th-century gatehouse survive from the Augustinian priory founded by William de Lovetot in 1103.

This large religious establishment was originally called Radford Priory from the red soil of the ford. The monks also owned a corn mill at the Canch, and area whose name comes from a dialect word meaning a part of a field.

The de Lovetots were followed as lords of the manor by the Furnivals. Maud Furnival financed construction of the Lady Chapel in 1240. One of the church’s few remaining ancient effigies is that of Thomas Furnival, who fought in the battle of Crécy in 1346.

The priory was closed in 1539 by King Henry VIII. Most of its buildings were pulled down, including part of the church, formerly almost three times its present size. Henry later granted the priory lands to the 5th Earl of Shrewsbury, a descendant of Maud Furnival.

The gatehouse may have been kept because it served non-religious functions. The monks had used it to put up travellers, and were therefore exempted from some taxes. It had also been used as a tollhouse and became a charity schoolroom in the 17th century. A replica of the gatehouse stands at nearby Clipstone.

Text about Worksop Manor

The text reads: Worksop Manor was the seat of the ancient Lords of Worksop. The Talbot family had owned Worksop Manor since the 14th century. For some time in 1568, it was the prison of Mary, Queen of Scots. In the 1580s, a new house, probably descended by Robert Smythson, was built for the hugely wealthy George Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury.

King James stayed at the new house in 1603 on his way south to take the throne of England. The house passed by marriage to the Duke of Norfolk’s family from the end of the 17th century until 1840. In 1761, the Smythson house burned down and James Paine was commissioned to build a replacement.

Although only part of the planned design was built, even this was on a palatial scale. After the death of the 9th Duke in 1777, the house fell into disrepair. In 1838, the estate was sold to the Duke of Newcastle of nearby Clumber Park, who largely demolished it. The surviving stable, service wing and part of the eastern end of the main range were reformed into a new mansion. Since around 1905, the estate has been home to the Worksop Manor Stud, which breeds thoroughbred horses.

External photograph of the building – main entrance