Pub history

The Imperial

Previously the Imperial Hotel, from 1923 until 1994, this had been converted from Elmfield House, built in 1810 for the County Surveyor James Green. The orangery was added by Dr William Buller Henderson, who purchased the property in 1897.

Previously the Imperial Hotel, from 1923 until 1994, this had been converted from Elmfield House, built in 1810 for the County Surveyor James Green. The orangery was added by Dr William Buller Henderson, who purchased the property in 1897.

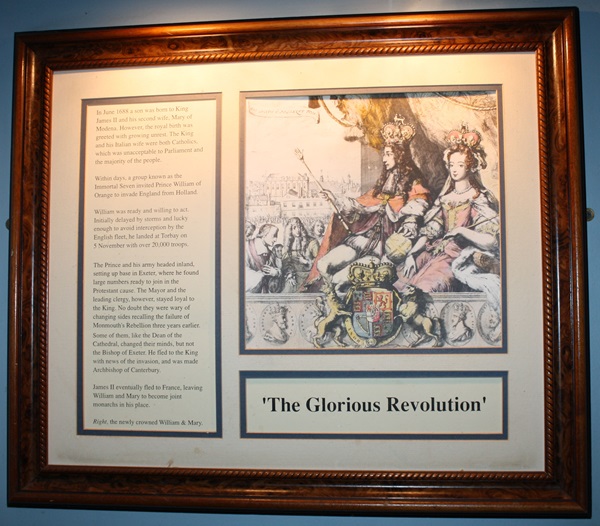

A framed drawing and text about the Glorious Revolution

The text reads: In June 1688, a son was born to King James II and his second wife, Mary of Modena. However, the royal birth was greeted with growing unrest. The King and his Italian wife were both Catholics, which was unacceptable to Parliament and the majority of the people.

Within days, a group known as the Immortal Seven invited Prince William of Orange to invade England from Holland.

William was ready and willing to act. Initially delayed by storms and lucky enough to avoid interception by the English fleet, he landed at Torbay on 5 November with over 20,000 troops.

The Prince and his army headed inland, setting up base in Exeter, where he found large numbers ready to join in the Protestant cause. The mayor and the leading clergy, however, stayed loyal to the King. No doubt they were wary of changing sides, recalling the failure of the Monmouth Rebellion three years earlier.

Some of them, like the dean of the cathedral, changed their minds, but not the Bishop of Exeter. He fled to the King with news of the invasion and was made Archbishop of Canterbury.

James II eventually fled to France, leaving William and Mary to become joint monarchs in his place.

Right: The newly crowned William and Mary

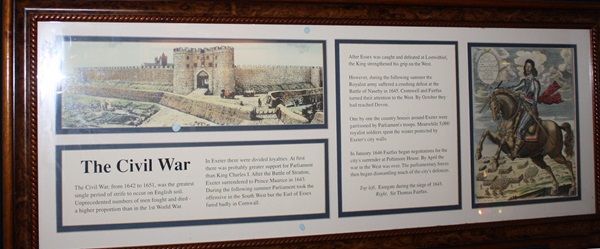

Framed drawings and text about the Civil War (1642–51)

The text reads: The Civil War, from 1642 to 1651, was the greatest single period of strife to occur on English soil. Unprecedented numbers of men fought and died – a higher proportion than in the First World War.

In Exeter, there were divided loyalties. At first, there was probably greater support for Parliament than for King Charles I. After the Battle of Stratton, Exeter surrendered to Prince Maurice in 1643. During the following summer, Parliament took the offensive in the South West, but the Earl of Essex fared badly in Cornwall.

After Essex was caught and defeated at Lostwithiel, the King strengthened his grip on the West.

However, during the following summer, the Royalist army suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Naseby in 1645. Cromwell and Fairfax turned their attention to the West. By October, they had reached Devon.

One by one, the country houses around Exeter were garrisoned by Parliament’s troops. Meanwhile 5,000 Royalist soldiers spent the winter protected by Exeter’s city walls.

In January 1646, Fairfax began negotiations for the city’s surrender at Politmore House. By April, the war in the West was over. The Parliamentary forces then began dismantling many of the city’s defences.

Top, left: Eastgate during the siege of 1643

Right: Sir Thomas Fairfax

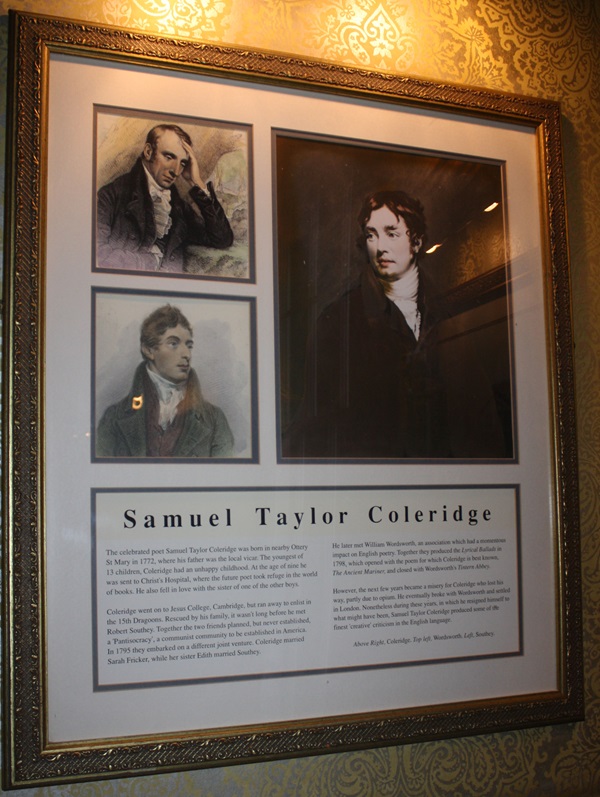

Framed drawings and text about Samuel Taylor Coleridge

The text reads: The celebrated poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge was born in nearby Ottery St Mary in 1772, where his father was the local vicar. The youngest of 13 children, Coleridge had an unhappy childhood. At the age of nine, he was sent to Christ’s Hospital, where the future poet took refuge in the world of books. He also fell in love with the sister of one of the other boys.

Coleridge went on to Jesus College, Cambridge, but ran away to enlist in the 15th Dragoons. Rescued by his family, it wasn’t long before he met Robert Southey. Together, the two friends planned, but never established, a ‘Pantisocracy’, a communist community to be established in America. In 1795, they embarked on a different joint venture. Coleridge married Sarah Fricker, while her sister Edith married Southey.

He later met William Wordsworth, an association which had a momentous impact on English poetry. Together, they produced the Lyrical Ballads in 1798, which opened with the poem for which Coleridge is best known, ‘The Ancient Mariner’, and closed with Wordsworth’s ‘Tintern Abbey’.

However, the next few years became a misery for Coleridge, who lost his way, partly due to opium. He eventually broke with Wordsworth and settled in London. Nonetheless, during these years, in which he resigned himself to what might have been, Samuel Taylor Coleridge produced some of the finest ‘creative criticism’ in the English language.

Above, right: Coleridge

Top, left: Wordsworth

Left: Southey

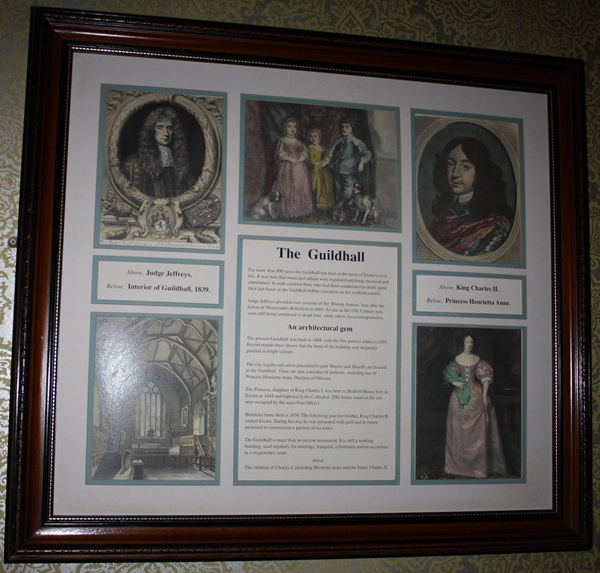

Framed drawings and text about the history of the Guildhall

The text reads: For more than 800 years, the Guildhall has been at the heart of Exeter’s civic life. It was here that municipal affairs were regulated, and Kings received and entertained. In stark contrast, those who had been condemned to death spent their last hours in the Guildhall before execution on the scaffold outside.

Judge Jeffreys presided over sessions of the ‘Bloody Assizes’ here after the defeat of the Monmouth Rebellion in 1685. As late as the 19th century, men were still being sentenced to death here, while others faced transportation.

The present Guildhall was built in 1468, with the fine portico added in 1592. Recent repairs have shown that the front of the building was originally painted in bright colours.

The city regalia and silver presented to past mayors and sheriffs are housed in the Guildhall. There are also a number of portraits, including one of Princess Henrietta Anne, Duchess of Orleans.

The Princess, daughter of King Charles I, was born in Bedford House here in Exeter in 1644 and baptised in the Cathedral. (The house stood on the site now occupied by the main post office.)

Henrietta Anne died in 1670. The following year, her brother, King Charles II, visited Exeter. During his stay, he was presented with gold and in return promised to commission a portrait of his sister.

The Guildhall is more than an ancient monument. It is still a working building, used regularly for meetings, banquets, exhibitions and on occasions as a magistrates’ court.

Top, centre: The children of Charles I, including Henrietta Anne and the future Charles II

Top, left: Judge Jeffreys

Top, right: King Charles II

Bottom, left: Interior of Guildhall, 1839

Bottom, right: Princess Henrietta Anne

Framed drawings, photographs and text about General Sir Redvers Buller VC

The text reads: The Buller family were landowners in and around Exeter for several centuries. Their most famous son has an impressive equestrian statue in Exeter.

General Sir Redvers Buller VC was born in 1839 at Downes, near Crediton. He Joined the King’s Own Rifles and soon had a reputation for daring. He served in Canada, China and the Gold Coast before being sent to South Africa to fight in the Zulu Wars, where he won his VC for rescuing three comrades. Buller later served in the Sudan, helping in the attempt to rescue General Gordon at Khartoum. His last campaign was the Boar War.

Above, left: The celebrated General attended the unveiling of his statue in Queen’s Street, in 1905

Above, centre: A Spy cartoon of Buller in Vanity Fair, 1900

Above, right: An artist’s impression of the exploit which won Buller his VC

Right: Buller on his charger ‘Ironmonger’

Left: General Sir Redvers Buller VC, KCB, KCMG

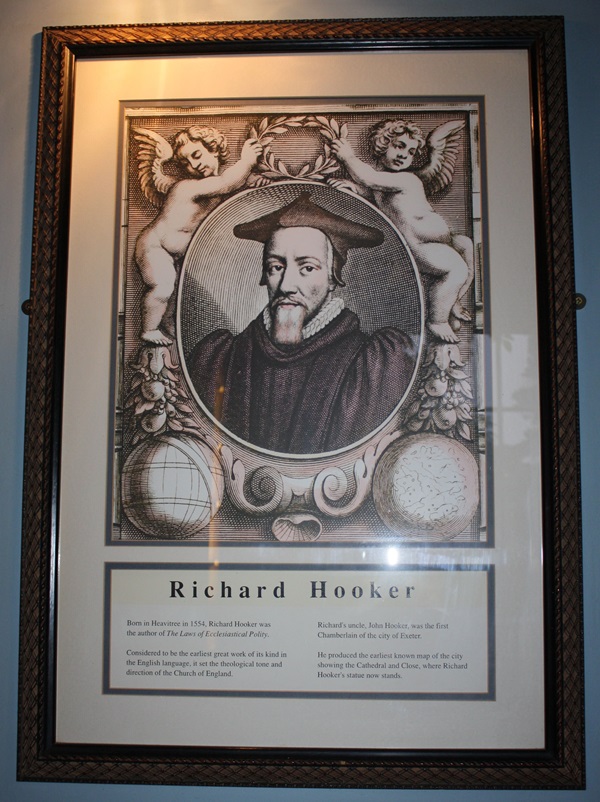

A framed portrait and text about Richard Hooker

The text reads: Richard Hooker

Born in Heavitree in 1554, Richard Hooker was the author of The Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity.

Considered to be the earliest great work of its kind in the English language, it set the theological tone and direction of the Church of England.

Richard’s uncle, John Hooker, was the first chamberlain of the city of Exeter.

He produced the earliest known map of the city showing the Cathedral and Close, where Richard Hooker’s statue now stands.

Framed portrait of Richard Hooker

Framed portrait of Joanna Southcott

A framed drawing of Margaret Thatcher, otherwise known as the Iron Lady

The text reads: Lady Margaret Thatcher made Ready. For Dear Bill: Letters of Denis Thatcher by Richard Ingrams and John Wells

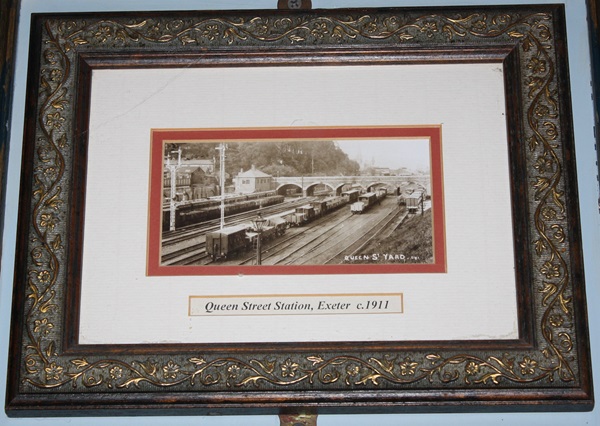

A framed photograph of Queen Street Station, Exeter c1911

A framed photograph of St Mary’s Church, Exeter, c1907

A framed photograph of Exeter’s first electric tram, 4 April 1905

A framed print of King Richard III

A framed photograph of Charles Babbage – forerunner and pioneer of the computer age

A handmade metal plaque, comprising the months of the year with the relevant star sign just below each

A time-worn statue of a gymnast, located on the stairs near the main entrance

A piece of text about the Ballroom

The text reads: The decoration and the doors in this room were ‘imported’. They were brought here from Haldon House, which was built for Sir George Chudleigh between 1725 and 1740.

Sir George lavished the enormous sum of £120,000 on what was intended as a replica of Buckingham Palace.

Designed by Robert Adam, it was one of the five largest houses in England. Haldon House stood at nearby Dunchideock.

If you look out to the southwest skyline from the entrance to The Imperial, you can see Belvedere Folly (which has recently been restored).

This was part of the Haldon House estate. Apart from the Folly, all that remains is what is now the Haldon House Hotel, and this is just a portion of the old servants’ quarters.

How these decorations came to be here is both funny and sad. In the 1920s, the building (then known as Elmfield House) was purchased by the Pollard family.

At much the same time, the owner of Haldon House was gambling away his fortune. He reached a point where he would sell off parts of his house in exchange for cash.

Builders in need of bricks, cornerstones and the like would pay cash, knock down the bit they needed and carry it away.

The destitute gambler kept himself in funds whilst his house was broken up around him.

When the Pollards began to improve Elmfield House, their builder went off to Haldon House. Having found what he was looking for, he returned with the interior you see around you.

The pilasters, mouldings, even the Cuban mahogany doors, were all carried from the ever-diminishing Haldon House.

A framed photograph of the Ballroom in its heyday

An internal photograph of the Ballroom today

The pilaster mouldings which were referred to in the text above

An internal photograph of the Orangery

This had formerly been part of Streatham House and dates from the early 1900s

External photograph of the building – main entrance