Pub history

The Hippodrome

The former Hippodrome is close to the junction with Broad Street, the town’s main shopping area. The 900-seat cinema opened on 8 February 1929, built for March Amusements at a cost of £20,000 (see the initials ‘MA’ atop the Dartford Road façade). The stage doors are in the side street on Darthill Road. After a change of ownership in the 1960s, this became a bingo hall. Although films were reintroduced recently, the little-changed Hippodrome closed down in 2009.

The former Hippodrome is located close to the junction with Broad Street, the town’s main shopping area. The 900-seat cinema opened on 8 February 1929, built for March Amusements at a cost of £20,000 (the initials ‘MA’ can be seen atop the Dartford Road façade). There was also a stage and five dressing rooms. The stage doors are in the side street on Darthill Road. After a change of ownership in the 1960s, this became a bingo hall. Although films were reintroduced recently, the little-changed Hippodrome closed down in 2009.

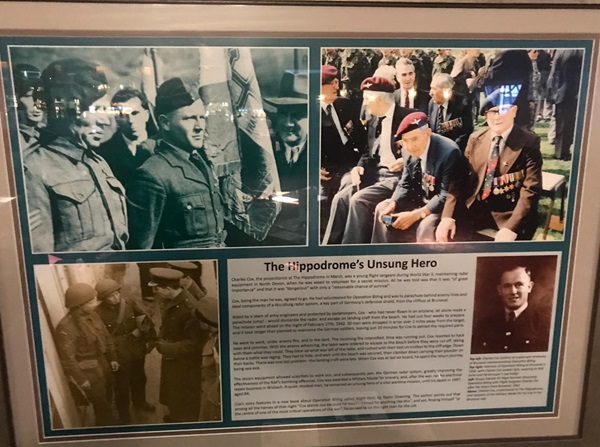

Photographs and text about The Hippodrome’s unsung hero

The text reads: Charles Cox, the projectionist at The Hippodrome in March, was a young flight sergeant during World War II, maintaining radar equipment in North Devon, when he was asked to volunteer for a secret mission. All he was told was that it was ‘of great importance’ and that it was ‘dangerous’ with only a ‘reasonable chance of survival’.

Cox, being the man he was, agreed to go. He had volunteered for Operation Biting and was to parachute behind enemy lines and steal components of a Wurzburg radar system, a key part of Germany’s defensive shield, from the clifftop at Bruneval.

Aided by a team of army engineers and protected by paratroopers, Cox – who had never flown in an airplane, let alone made a parachute jump! – would dismantle the radar, and escape on landing craft from the beach. He had just four weeks to prepare. The mission went ahead on the night of 27 February 1942. Twenty men were dropped in error over two miles away from the target, and it took longer than planned to overcome the German soldiers, leaving just 10 miles for Cox to extract the required parts.

He went to work, under enemy fire, and in the dark. The incoming fire intensified; time was running out. Cox resorted to hacksaws and jemmies. With the enemy advancing, the team were ordered to escape to the beach before they were cut off, taking with them what they could. They blew up what was left of the radar and rushed with their loot on trolleys to the cliff edge. Down below, a battle was raging. They had to hide, wait until the beach was secured, then clamber down, carrying their plunder on their backs. There was one last problem – the landing craft were late. When Cox was last onboard, he spent the return journey being seasick.

The stolen equipment allowed scientists to work out, and subsequently jam, the German radar system, greatly improving the effectiveness of the RAF’s bombing offensive. Cox was awarded a Military Medal for bravery, and, after the war, ran his electrical repair business in Wisbech. A quiet, modest man, he remained an unsung hero of a vital wartime mission, until his death in 1997, aged 84.

Cox’s story features in a new book about Operation Biting called Night Raid, by Taylor Downing. The author points out that among all the heroes of that night, ‘Cox stands out because he wasn’t trained for anything like this’ and yet, finding himself ‘at the centre of one of the most critical operations of the war’, he proved to be the right man for the job.

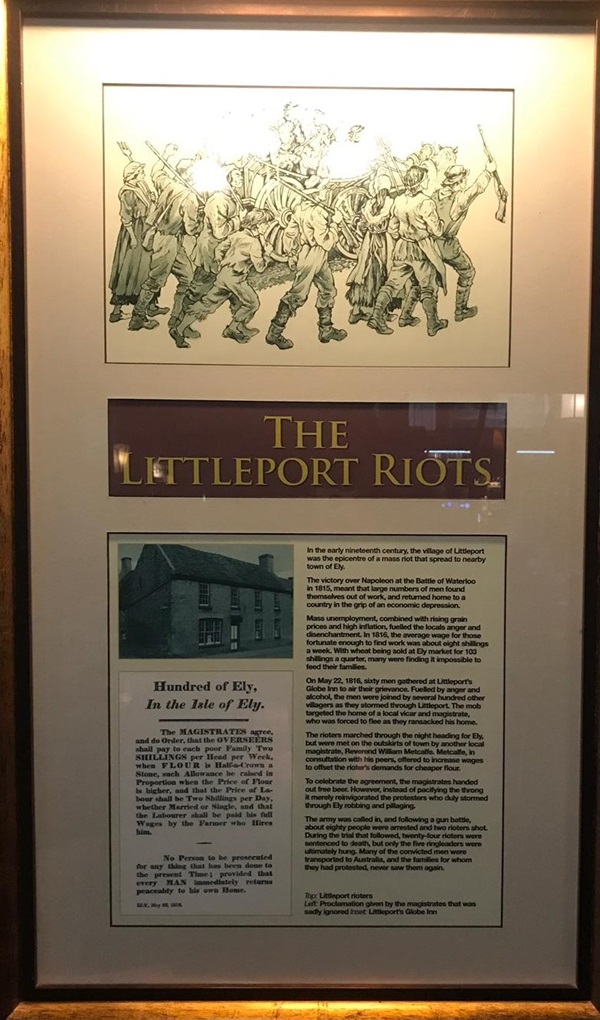

Illustration, photograph and text about the Littleport Riots

The text reads: In the early 19th century, the village of Littleport was the epicentre of a mass riot that spread to the nearby town of Ely.

The victory over Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 meant that large numbers of men found themselves out of work, and returned home to a country in the grip of an economic depression.

Mass unemployment, combined with rising grain prices and high inflation, fuelled the locals’ anger and disenchantment. In 1816, the average wage for those fortunate enough to find work was about eight shillings a week. With wheat being sold at Ely market for 103 shillings a quarter, many were finding it impossible to feed their families.

On 22 May 1816, 60 men gathered at Littleport’s Globe Inn to air their grievance. Fuelled by anger and alcohol, the men were joined by several hundred other villagers as they stormed through Littleport. The mob targeted the home of a local vicar and magistrate, who was forced to flee as they ransacked his home.

The rioters marched through the night heading for Ely but were met on the outskirts of town by another local magistrate, Reverend William Metcalfe. Metcalfe, in consultation with his peers, offered to increase wages to offset the rioters’ demands for cheaper flour.

To celebrate the agreement, the magistrates handed out free beer. However, instead of pacifying the throng it merely reinvigorated the protesters, who duly stormed through Ely robbing and pillaging.

The army was called in, and following a gun battle, about 80 people were arrested and two rioters shot. During the trial that followed, 24 rioters were sentenced to death, but only the five ringleaders were ultimately hung. Many of the convicted men were transported to Australia, and the families for whom they had protested never saw them again.

Top: Littleport rioters

Left: Proclamation given by the magistrates that was sadly ignored

Inset: Littleport’s Globe Inn

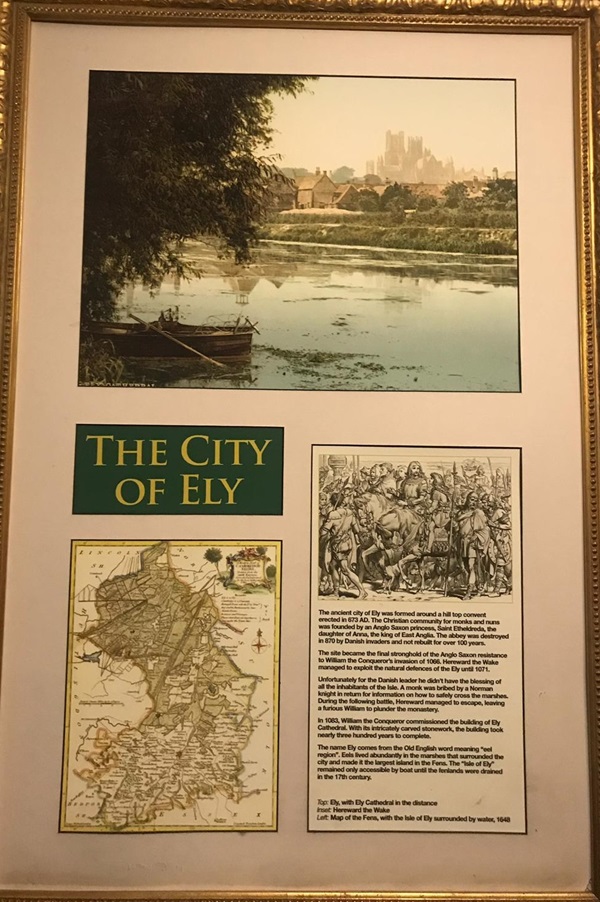

Illustrations, prints and text about the history of Ely

The text reads: The ancient city of Ely was formed around a hilltop convent erected in AD 673. The Christian community for monks and nuns was founded by an Anglo-Saxon princess, Saint Etheldreda, the daughter of Anna, the king of East Anglia. The abbey was destroyed in 870 by Danish invaders and not rebuilt for over 100 years.

The site became the final stronghold of the Anglo-Saxon resistance to William the Conqueror’s invasion in 1066. Hereward the Wake managed to exploit the natural defences of Ely until 1071.

Unfortunately for the Danish leader, he didn’t have the blessing of all the inhabitants of the isle. A monk was bribed by a Norman knight in return for information on how to safely cross the marshes. During the following battle, Hereward managed to escape, leaving a furious William to plunder the monastery.

In 1083, William the Conqueror commissioned the building of Ely Cathedral. With its intricately carved stonework, the building took nearly 300 years to complete.

The name Ely comes from the Old English word meaning ‘eel region’. Eels lived abundantly in the marshes that surrounded the city and made it the largest island in the Fens. The ‘Isle of Ely’ remained only accessible by boat until the Fenlands were drained in the 17th century.

Top: Ely, with Ely Cathedral in the distance

Inset: Hereward the Wake

Left: Map of the Fens, with the Isle of Ely surrounded by water, 1648

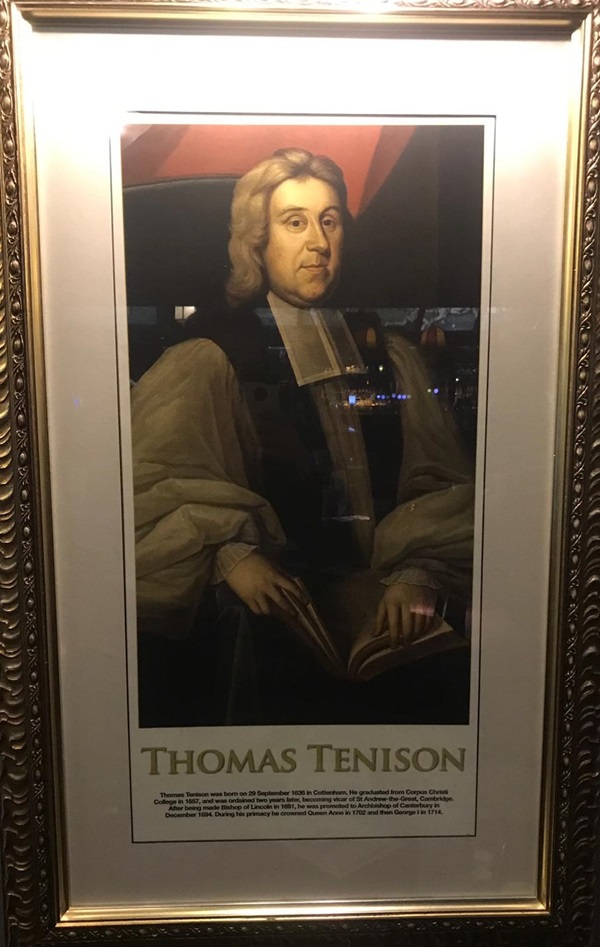

A print and text about Thomas Tenison

The text reads: Thomas Tenison was born on 29 September 1636 in Cottenham. He graduated from Corpus Christi College in 1657 and was ordained two years later, becoming vicar of St Andrew the Great, Cambridge. After being made Bishop of Lincoln in 1691, he was promoted to Archbishop of Canterbury in December 1694. During his primacy, he crowned Queen Anne in 1702 and then George I in 1714.

A print and text about Henry Hervey Baber

The text reads: Henry Hervey Baber was born of 22 August 1775 in Slingsby, Yorkshire, he enrolled at All Souls College, Oxford, as a bible scholar, and following his graduation became the assistant librarian at the British Museum. He was promoted to Keeper of the Printed Books in 1812, and the following year requested the approval and finance of the prime minster, Robert Jenkinson, to produce a copy of the Alexandrian manuscript, a fifth-century Greek bible. When the reproduction was published in 1828, he was rewarded by the Crown with the rectory of St James’ Church, Stretham. He served in the parish for more than 40 years until his death in 1869.

An illustration and text about Isaac Casaubon

The text reads: Isaac Casaubon was born on 18 February 1559 in Switzerland. His parents were French Huguenot refugees who returned to France in 1562, following a declaration of religious tolerance. He was solely educated by his father until he was sent to the Academy of Geneva, to study Greek when he was 19. When his teacher, Francis Portus, died just three years later, he recommended Casaubon to be his successor.

Casaubon remained at Geneva as professor of Greek until 1596, during which time he became a consummate Greek and Classical scholar. He then took a position in Paris as Henry IV’s sub-librarian, but when the monarch was assassinated, he travelled to England in 1610 to escape persecution.

By this time, he was regarded by many as one of the most intellectual men in Europe, and he was warmly welcomed by James I. He also became close friends with Lancelot Andrewes, Bishop of Ely, and together they spent a great deal of time travelling in Cambridgeshire, including a six-week stay in Downham in 1611.

External photograph of the building – main entrance