Pub history

The George

This pub stands on the site of the Old George Inn which traded here from at least the 15th century to the late 18th century. In the early 1900s, the site was occupied by a fruiterer and a butcher’s shop. During the 1930s, Tesco moved into number 2, later occupying the whole site. Just before the present George opened, in 1996, archaeological excavations unearthed evidence of Iron Age and early Roman occupation, along with a medieval well.

This pub stands on the site of the Old George Inn which traded here from at least the 15th century to the late 18th century. In the early 1900s, the site was occupied by a fruiterer and a butcher’s shop. During the 1930s, Tesco moved into number 2, later occupying the whole site. Just before the present George opened, in 1996, archaeological excavations unearthed evidence of Iron Age and early Roman occupation, along with a medieval well.

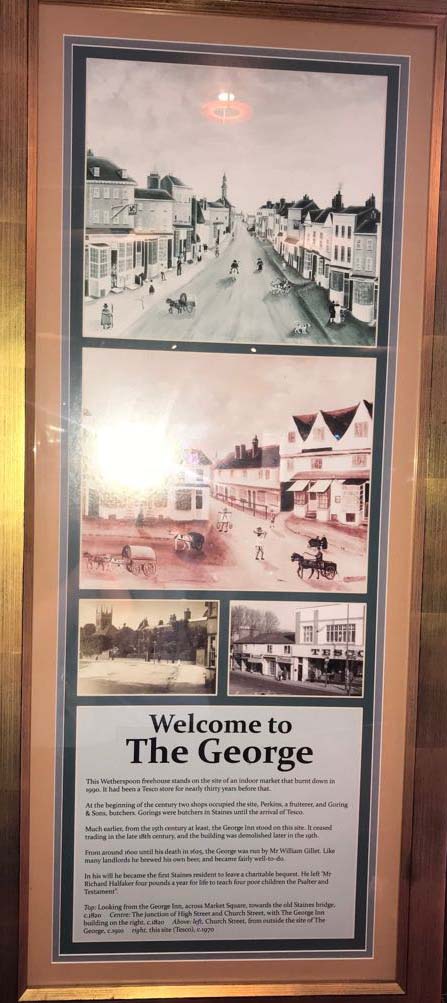

Prints and text about The George

The text reads: This Wetherspoon free house stands on the site of an indoor market that burnt down in 1990. It had been a Tesco store for nearly 30 years before that.

At the beginning of the century, two shops occupied the site. Perkins, a fruiterer, and Goring & Sons butchers. Goring’s were butchers in Staines until the arrival of Tesco.

Much earlier, from the 15th century at least, the George Inn stood on this site. It ceased trading in the late 18th century, and the building was demolished later in the 19th.

From around 1600 until his death in 1625, the George was run by Mr William Gillet. Like many landlords, he brewed his own beer, and became fairly well-to-do.

In his will, he became the first Staines resident to leave a charitable bequest. He left ‘Mr Richard Halfaker four pounds a year for life to teach four poor children the Psalter and Testament’.

Top: Looking from the George Inn, across Market Square, towards the old Staines bridge, c1820

Centre: The junction of High Street and Church Street, with The George Inn building on the right, c1820

Above, left: Church Street, from outside the site of The George, c1910

Above, right: This site (Tesco), c1970

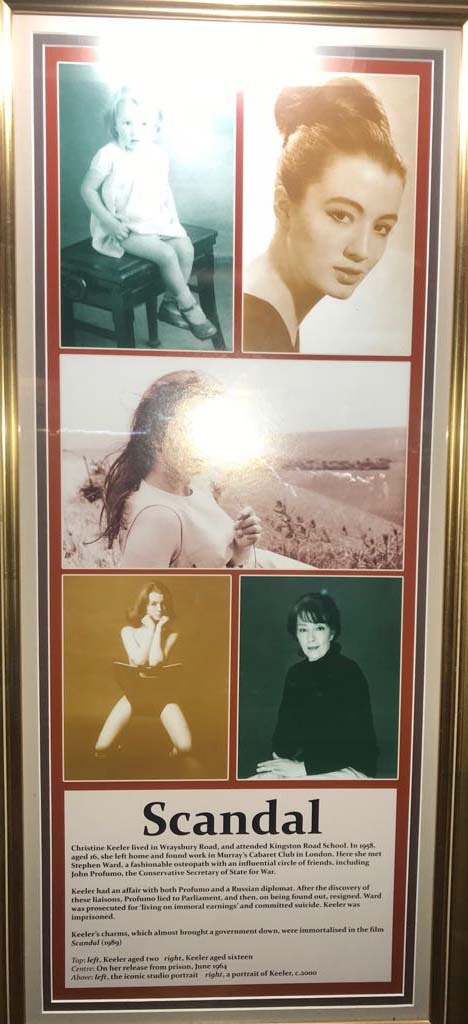

Photographs and text about Christine Keeler

The text reads: Christine Keeler lived in Wraysbury Road and attended Kingston Road School. In 1958, aged 16, she left home and found work in Murray’s Cabaret Club in London. Here she met Stephen Ward, a fashionable osteopath with an influential circle of friends, including John Profumo, the Conservative Secretary of State for War.

Keeler had an affair with both Profumo and a Russian diplomat. After the discovery of these liaisons, Profumo lied to Parliament, and then, on being found out, resigned. Ward was prosecuted for ‘living on immoral earnings’ and committed suicide. Keeler was imprisoned.

Keeler’s charms, which almost brought a government down, were immortalised in the film Scandal (1989).

Top, left: Keeler aged two

Right: Keeler aged 16

Centre: On her released from prison, June 1964

Above, left: The iconic studio portrait

Above, right: A portrait of Keeler, c2000

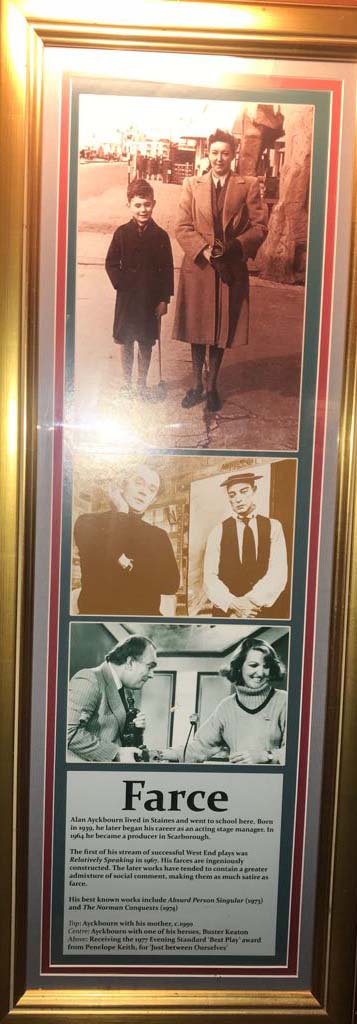

Photographs and text about Alan Ayckbourn

The text reads: Alan Ayckbourn lived in Staines and went to school here. Born in 1939, he later began his career as an acting stage manager. In 1964, he became a producer in Scarborough.

The first of his stream of successful West End plays was Relatively Speaking in 1967. His farces are ingeniously constructed. The later works have tended to contain a greater admixture of social comment, making them as much satire as farce.

His best-known works include Absurd Person Singular (1973) and The Norman Conquests (1974).

Top: Ayckbourn with his mother, c1950

Centre: Ayckbourn with one of his heroes, Buster Keaton

Above: Receiving the 1977 Evening Standard Best Play award from Penelope Keith, for Just Between Ourselves

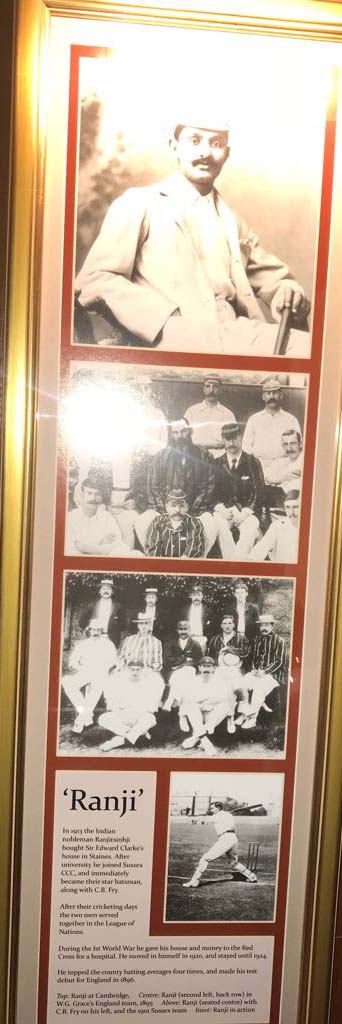

Photographs and text about Ranjitsinhji

The text reads: In 1913, the Indian nobleman Ranjitsinhji bought Sir Edward Clarke’s house in Staines. After university, he joined Sussex CCC, and immediately became their star batsman, along with CB Fry.

After their cricketing days, the two men served together in the League of Nations.

During the First World War, he gave his house and money to the Red Cross for a hospital. He moved in himself in 1920, and stayed until 1924.

He topped the county batting averages four times, and made his test debut for England in 1896.

Top: Ranji at Cambridge

Centre: Ranji (second left, back row) in WG Grace’s England team, 1895

Above: Ranji (seated centre) with CB Fry on his left, and the 1901 Sussex team

Inset: Ranji in action

Photographs and text about fire services

The text reads: It was not until 1774 that the fire services were taken into public ownership. Before that, market forces operated.

House owners needed fire insurance with the company that ran the fire brigade; otherwise, they would be left to burn. An emblem of firemark was fixed to the front of insured houses, so the brigade knew at once whether they would be paid for attending.

Staines Brigade were housed in the fire station across the road from The George, from 1800. They had a Merryweather Steam Fire Engine in 1876, and in 1924 their first motorised engine. The brigade moved to Town Lane, Stanwell, in 1962.

Top: The fire brigade parading in High Street, c1900

Left: Staines’ fire brigade in Market Place, c1900

Above: The fire brigade, c1938

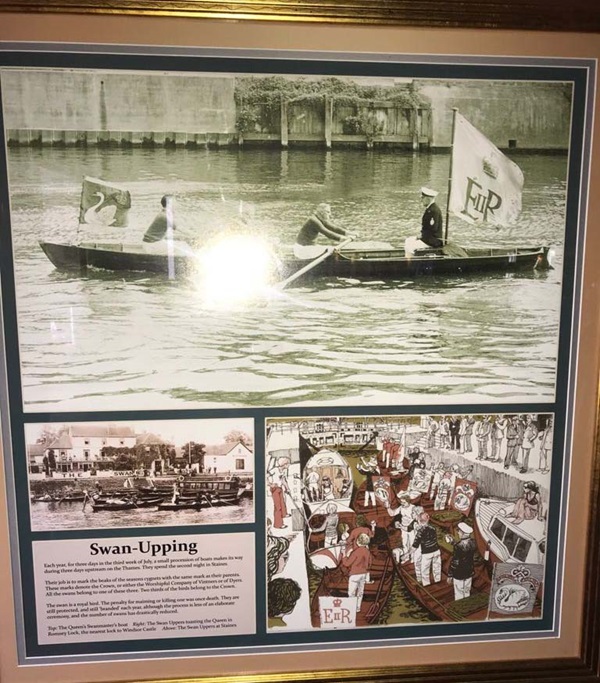

Photographs, an illustration and text about the Swan Uppers

The text reads: Each year, for three days in the third week of July, a small procession of boats makes its way during three days upstream on the Thames. They spend the second night in Staines.

Their job is to mark the beaks of the season’s cygnets with the same mark as their parents. These marks denote the Crown, or either the Worshipful Company of Vintners or of Dyers. All the swans belong to one of these three. Two thirds of the birds belong to the Crown.

The swan is a royal bird. The penalty for maiming or killing one was once death. They are still protected, and still ‘branded’ each year, although the process is less of an elaborate ceremony, and the number of swans has drastically reduced.

Top: The Queen’s Swanmaster’s boat

Right: The Swan Uppers toasting the Queen in Romney Lock, the nearest lock to Windsor Castle

Above: The Swan Uppers at Staines

Prints and text about Staines Bridge

The text reads: From Roman times until the 15th century, Staines had probably the only bridge above London. The medieval bridge was destroyed during the Civil War and replaced by a ferry.

It was rebuilt in 1683 but was soon inadequate for the increased traffic. A stone bridge, designed by Thomas Sandby, was opened in 1797, but collapsed. The old wooden bridge had to be re-opened. An iron bridge was opened in 1803 but soon developed cracks, and it was back to the old bridge again.

The iron bridge was examined by John Rennie, who designed London and Southwark bridges. It was when the old wooden bridge was pulled down. It was reinforced and re-opened in 1807, when the old wooden bridge was pulled down. The iron bridge was replaced by the present bridge in 1832. John Rennie’s sons, John and George, designed it, and it was situated upstream from its predecessor.

Tolls were charged to pay for it until 1871. The townspeople celebrated the repeal of the Act by throwing the toll gates into the river.

Top, left: A view of Staines and the river in 1723

Top, right: The new bridge, c1900

Left: The wooden bridge, 1799

Above, left: The iron bridge in 1825

Above, centre: An idyllic view of the new bridge, c1910

Above, right: Sandby’s stone bridge under construction in 1791

Right: Sandby’s bridge in 1799

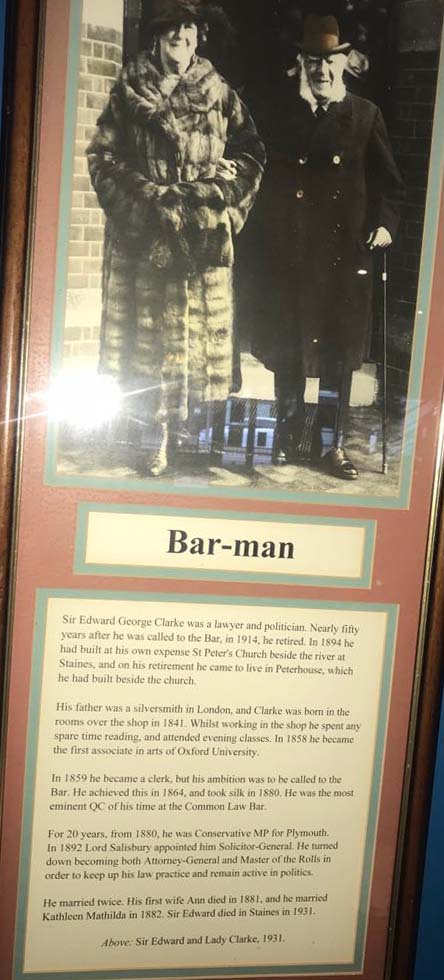

A print and text about Sir Edward George Clark

The text reads: Sir Edward George Clarke was a lawyer and politician. Nearly 50 years after he was called to the Bar, in 1914, he retired. In 1894, he had built at his own expense St Peter’s Church beside the river at Staines, and on his retirement, he came to live in Peterhouse, which he had built beside the church.

His father was a silversmith in London, and Clarke was born in the rooms over the shop in 1841. Whilst working in the shop, he spent any spare time reading, and attended evening classes. In 1858, he became the first associate in arts of Oxford University.

In 1859, he became a clerk, but his ambition was to be called to the Bar. He achieved this in 1864, and took silk in 1880. He was the most eminent QC of his time at the Common Law Bar.

For 20 years, from 1880, he was Conservative MP for Plymouth. In 1892, Lord Salisbury appointed him Solicitor-General. He turned down becoming both Attorney General and Master of the Rolls in order to keep up his law practice and remain active in politics.

He married twice. His first wife Ann died in 1881, and he married Kathleen Mathilda in 1882. Sir Edward died in Staines in 1931.

Above: Sir Edward and Lady Clarke, 1931

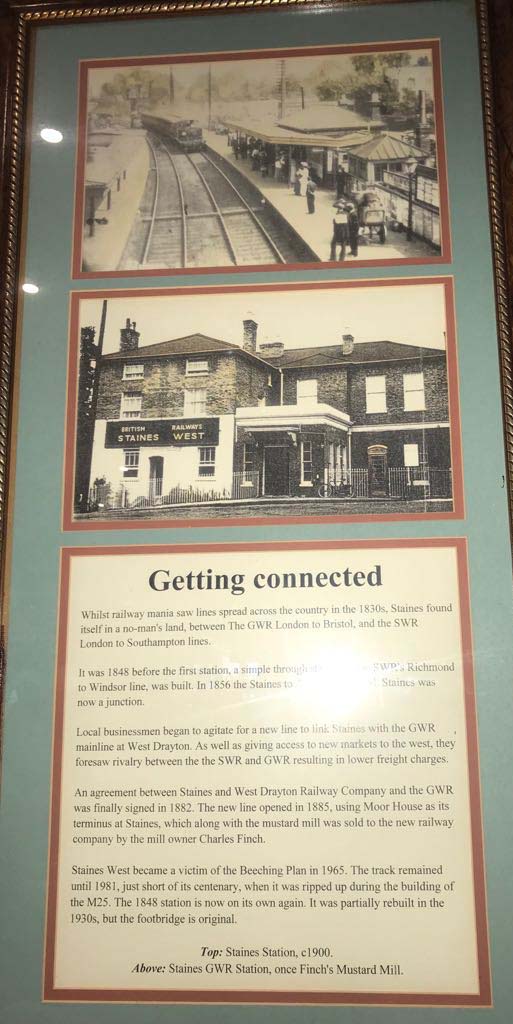

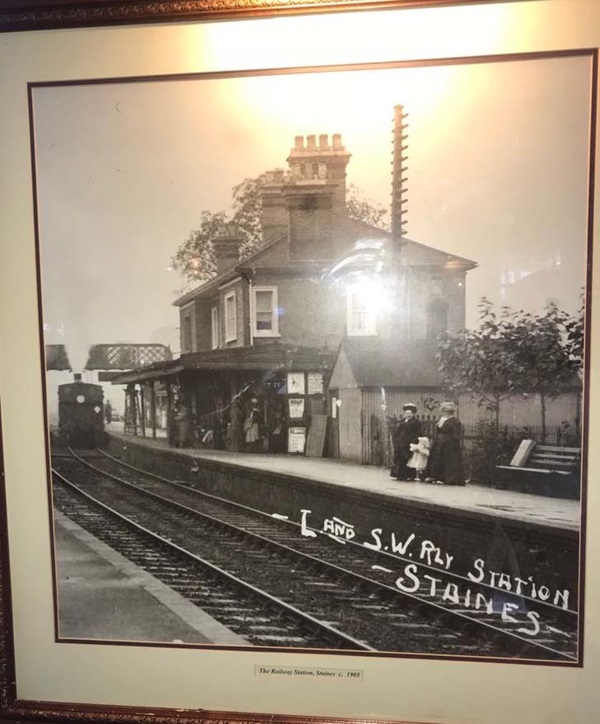

Prints and text about the railway in Staines

The text reads: Whilst railway mania saw lines spread across the country in the 1830s, Staines found itself in no-man’s land, between The GWR London to Bristol and the SWR London to Southampton lines.

It was 1848 before the first station, a simple through station on the SWR’s Richmond to Windsor line, was built. In 1856, the Staines to Ascot line opened. Staines was now a junction.

Local businessmen began to agitate or a new line to link Staines with the GWR mainline at West Drayton. As well as giving access to new markets to the west, they foresaw rivalry between the SWR and GWR resulting in lower freight charges.

An agreement between Staines and West Drayton Railway Company and the GWR was finally signed in 1882. The new line opened in 1885, using Moor House as its terminus at Staines, which along with the mustard mill was sold to the new railway company by the mill owner Charles Finch.

Staines West became a victim of the Beeching Plan in 1965. The track remained until 1981, just short of its centenary, when it was ripped up during the building of the M25. The 1848 station is now on its own again. It was partially rebuilt in the 1930s, but the footbridge is original.

Top: Staines Station, c1900

Above: Staines GWR Station, once Finch’s Mustard Mill

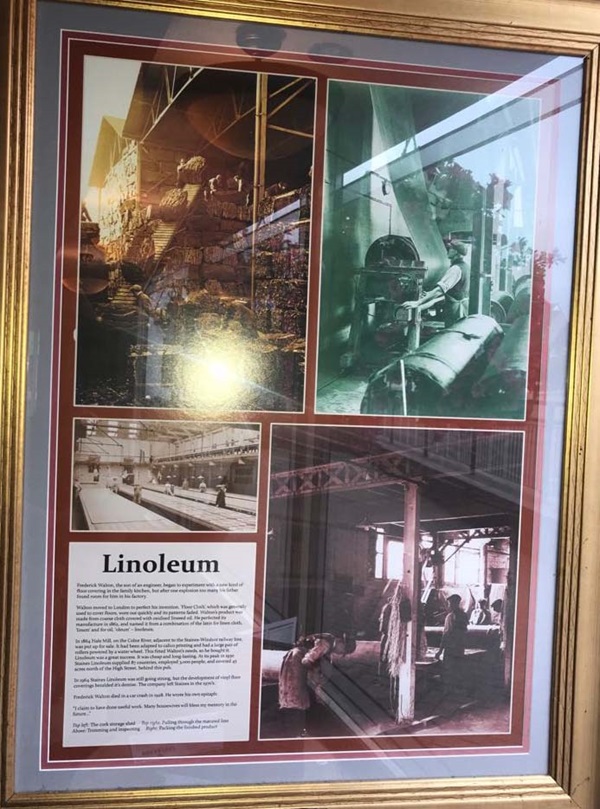

Photographs and text about Staines’ Linoleum

The text reads: Frederick Walton, the son of an engineer, began to experiment with a new kind of floor-covering in the family kitchen, but after one explosion too many, his father found room for him in his factory.

Walton moved to London to perfect his invention. ‘Floor Cloth’, which was generally used to cover floors, wore out quickly, and its patterns faded. Walton’s product was made from coarse cloth covered with oxidised linseed oil. He perfected its manufacture in 1862 and named it from a combination of the Latin for linen cloth, ‘linum’ and for oil, ‘oleum’ – linoleum.

In 1864, Hale Mill, on the Colne River, adjacent to the Staines–Windsor railway line, was put up for sale. It had been adapted to calico printing and had a large pair of rollers powered by a waterwheel. This fitted Walton’s needs, so he bought it. Linoleum was a great success. It was cheap and long-lasting. At its peak in 1930, Staines Linoleum supplied 87 countries, employed 3,000 people, and covered 45 acres north of the High Street, behind this pub.

In 1964, Staines Linoleum was still going strong, but the development of vinyl floor-coverings heralded its demise. The company left Staines in the 1970s.

Frederick Walton died in a car crash in 1928. He wrote his own epitaph: ‘I claim to have done useful work. Many housewives will bless my memory in the future…’

Top, left: The cork storage shed

Top, right: Pulling through the matured lino

Above: Trimming and inspecting

Right: Packing the finished product

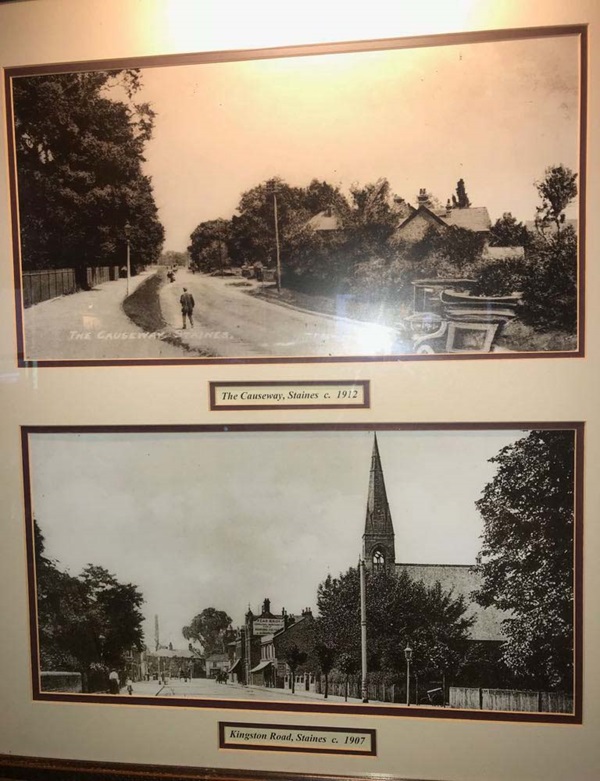

Photographs of roads in Staines

Top: The Causeway, Staines, c1912

Bottom: Kingston Road, Staines, c1907

Photographs of the Market Square, Staines

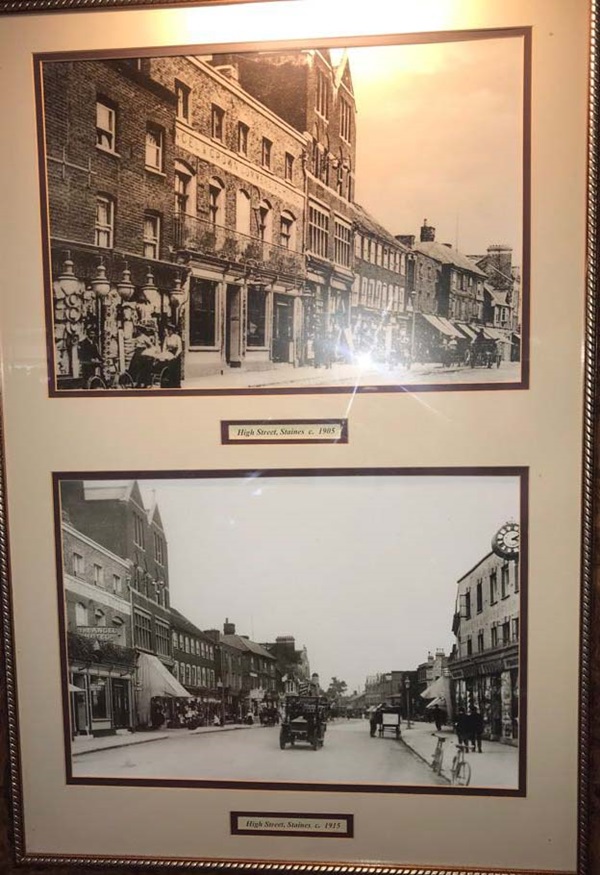

Photographs of High Street

Top: High Street, Staines, c1905

Bottom: High Street, Staines, c1915

A photograph of the railway station, Staines, c1905

External photograph of the building – main entrance