Pub history

The Flying Standard

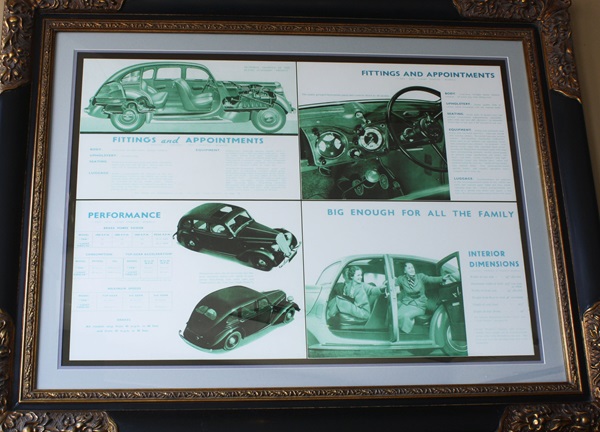

This is named after the fondly remembered motor car, part of a range of models made in Coventry from 1903 until the 1960s. Standard’s first car, the Motor Victoria, was built in 1903 by Reginald Maudslay, in Much Park Street. The Standard Nine was launched in 1927. Inexpensive, at £198, its success saw Standard through the ‘slump’ and it was still going strong when, in 1936, the Flying Standard models made their début.

This is named after the fondly remembered motor car, part of a range of models made in Coventry from 1903 until the 1960s. Standard’s first car, the Motor Victoria, was built in 1903 by Reginald Maudslay, in Much Park Street. The Standard Nine was launched in 1927. Inexpensive, at £198, its success saw Standard through the ‘slump’ and it was still going strong when, in 1936, the Flying Standard models made their début.

Illustrations and text about The Flying Standard

The text reads: The Flying Standard car was produced by the Standard Motor Company at its Canley Factory in Coventry.

The Factory was built to manufacture First World War Aeroplanes in 1916. Thereafter, it was used to build Standard Motor Cars including the Flying Standards that were built there from 1935 until the outbreak of the Second World War.

During the war, several aircraft were built at Canley, the most famous being the Mosquito Fighter Bomber. In 1944, Standard took over the Triumph company, and all post-war triumphs were built at Canley, alongside their Standard sisters. At its peak, nearly 12,000 people were employed at the ‘Standard, where Triumph cars continued to be made into the 1980’s. The factory has now been demolished, but a monument to this great Coventry company now stands in the appropriately named Herald Ave.

Text courtesy of the Standard Motor Club

www.standardmotorclub.org

Posters promoting cars manufactured by the Standard Motor Company

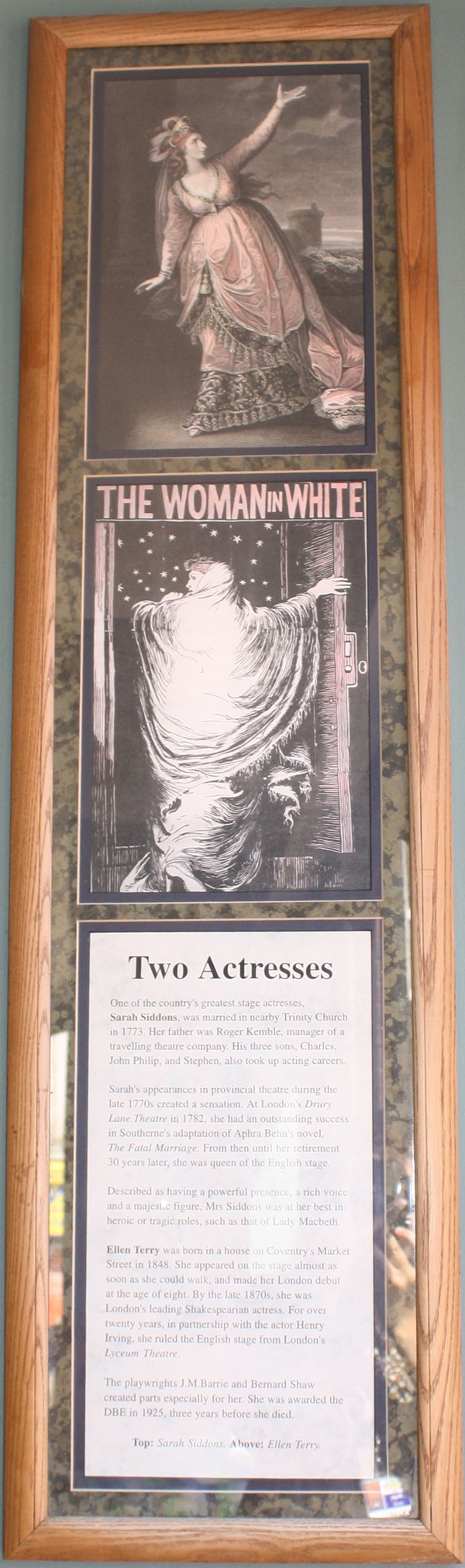

Illustrations and text about Sarah Siddons and Ellen Terry

The text reads: One of the country’s greatest stage actresses, Sarah Siddons, was married in nearby Trinity Church in 1773. Her father was Roger Kemble, manager of a travelling theatre company. His three sons – Charles, John Philip, and Stephen – also took up acting careers.

Sarah’s appearances in provincial theatre during the late 1770s created a sensation. At London’s Drury Lane Theatre in 1782, she had an outstanding success in Southerne’s adaptation of Aphra Behn’s novel, The Fatal Marriage. From then until her retirement 30 years later, she was queen of the English stage.

Described as having a powerful presence, a rich voice and a majestic figure, Mrs Siddons was at her best in heroic or tragic roles, such as that of Lady Macbeth.

Ellen Terry was born in a house on Coventry’s Market Street in 1848. She appeared on the stage almost as soon as she could walk, and made her London debut at the age of eight. By the late 1870s, she was London’s leading Shakespearian actress. For over 20 years, in partnership with the actor Henry Irving, she ruled the English stage from London’s Lyceum Theatre.

The playwrights JM Barrie and Bernard Shaw created parts especially for her. She was awarded the DBE in 1925, three years before she died.

Top: Sarah Siddons

Above: Ellen Terry

A photograph of Swanswell Gate when it was being used as a shop

Photographs of Trinity Street

Above: Construction of Trinity Street underway, showing the fire station and Sherbourne Culvert

Below: Hales Street and Trinity Street from Swanswell Gate

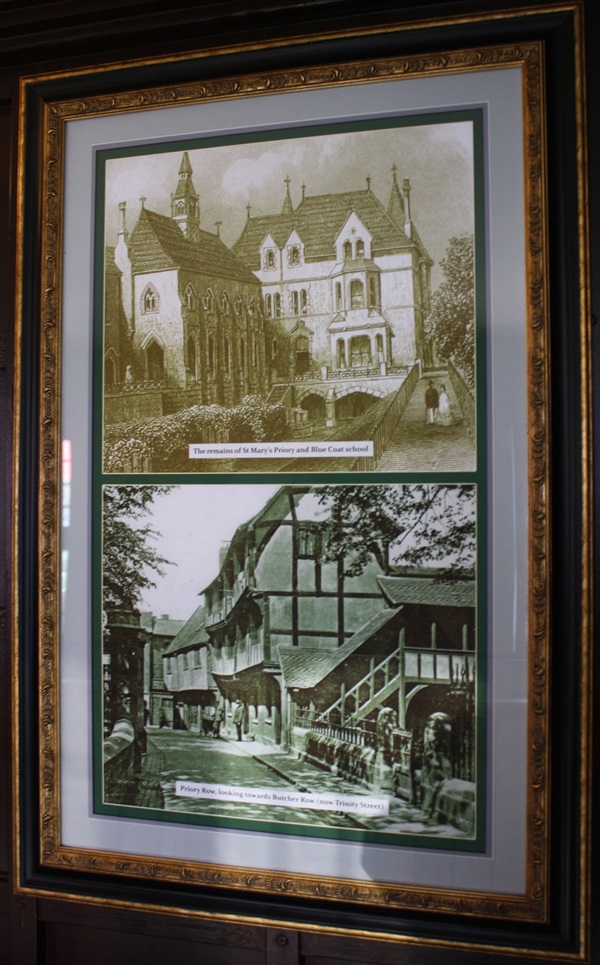

An illustration of the remains of St Mary’s Priory and Blue Coat school, and a photograph of Priory Row, looking towards Butcher Row (now Trinity Street)

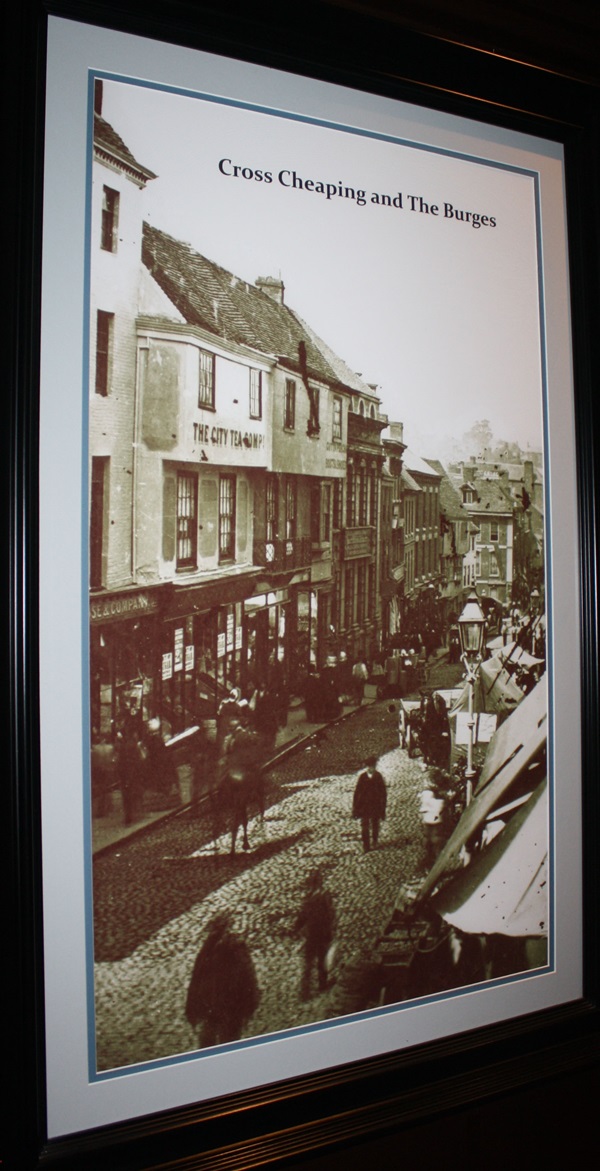

A photograph of Cross Cheaping and the Burges

Photographs of St Michael’s and Holy trinity from Pool Meadow, and a photograph of the Bull Ring and Butcher Row from Ironmonger Row, before demolition to make way for Trinity Street

A photograph of St Michael’s and Holy Trinity spires from Hales Street

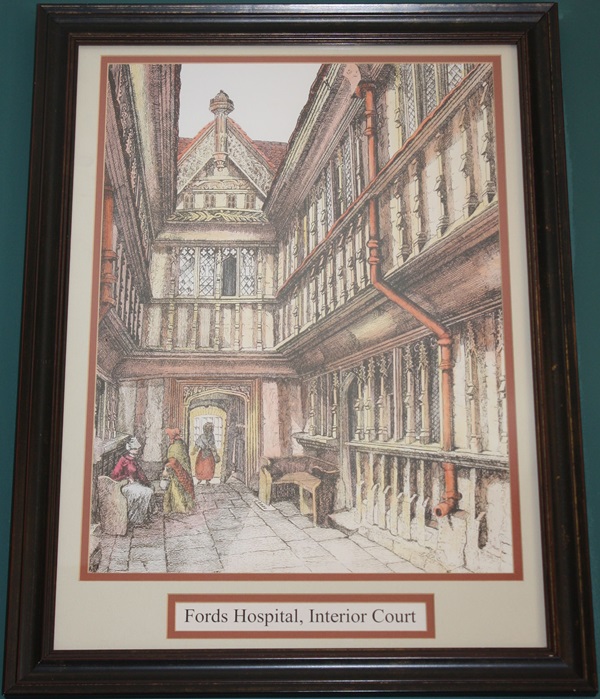

Illustrations of Fords Hospital and Palace Yard

Prints and text about the saying ‘sent to Coventry’

The text reads: This well-known saying, meaning a person being deliberately ignored by others, is first recorded in the mid-18th century. However, it is said to derive from the time of the English Civil Wars, 100 years earlier.

Coventry’s strong defences, and the support shown by its population for the Parliamentary cause, made it suitable as a holding-camp for Royalist prisoners. The citizens held the prisoners in such contempt that they simply ignored them. The prisoners were also unwelcome as the city had to feed and house them.

However, the phrase could be older and more sinister than it seems. On several occasions, prisoners facing death for crimes committed in other places were sent to Coventry for execution.

The first recorded case was that of the priest Riband, who tried to assassinate King Henry III. He was sent here from Woodstock to be dragged through the streets by horses. Later, rebels from Kent were brought to the city for execution.

Another saying involving the city’s name is ‘true as Coventry blue’. This dates back to the medieval heyday of the city’s cloth trade, and compliments the skill of the dyers and weavers here. Although originally used to describe thread dyed blue with woad, ‘Coventry blue’ later referred to top-quality cloth, woven and dyed in the city and often sent for export as a luxury item.

Left: Parliament’s Man – The Earl of Essex, Recorder for the City of Coventry during the Civil War

Right: King’s Man – Prince Rupert, who failed to take the city for the King

Above: King Charles I and Queen Henrietta Maria

An illustration of The Old Mayors Parlour, Cross Cheaping

An illustration of Fords Hospital, Interior Court

Illustrations of (clockwise from top-left) Mill Lane Gate, Gosford Gate, Spon Gate and Grey Friars Gate

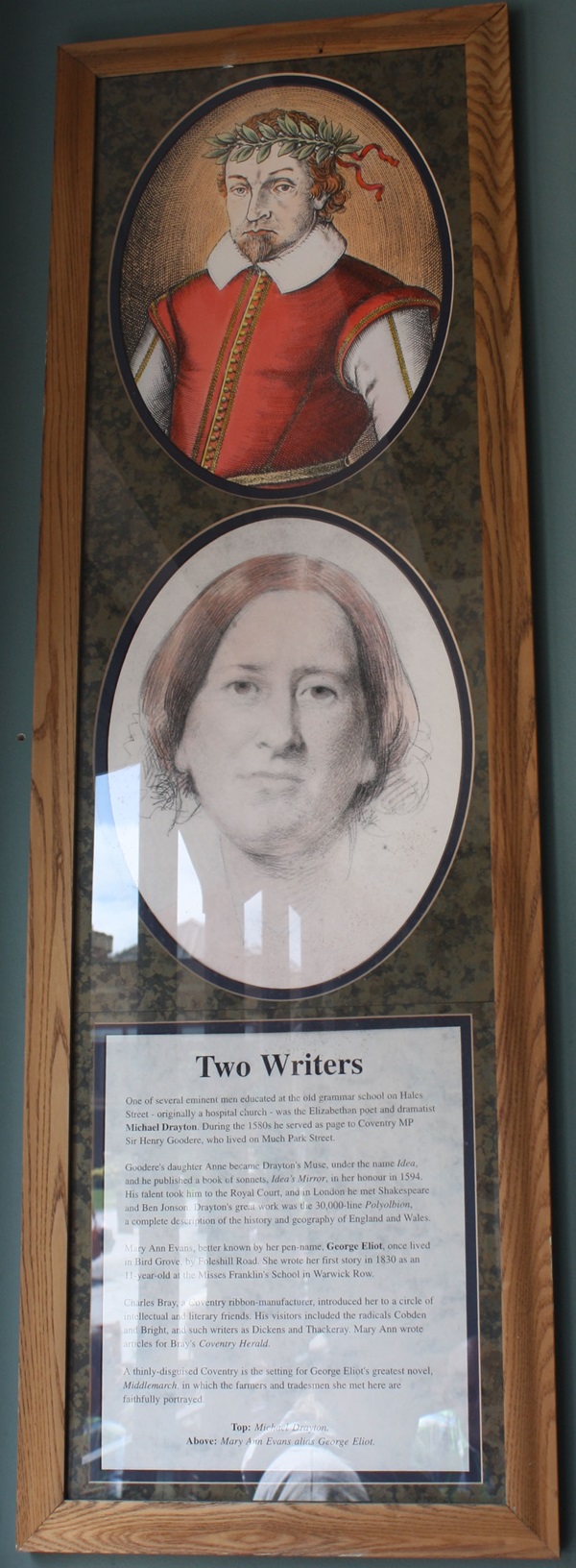

Illustrations and text about Michael Drayton and George Eliot

The text reads: One of several eminent men educated at the old grammar school on Hales Street – originally a hospital church – was the Elizabethan poet and dramatist Michael Drayton. During the 1580s, he served as page to Coventry MP Sir Henry Goodere, who lived on Much Park Street.

Goodere’s daughter Anne became Drayton’s muse, under the name Idea, and he published a book of sonnets, Idea’s Mirror, in her honour in 1594. His talent took him to the Royal Court, and in London he met Shakespeare and Ben Jonson. Drayton’s great work was the 30,000-line Polyolbion, a complete description of the history and geography of England and Wales.

Mary Ann Evans, better known by her pen-name, George Eliot, once lived in Bird Grove, by Foleshill Road. She wrote her first story in 1830 as an 11-year old at the Miss Franklin’s School in Warwick Row.

Charles Bray, a Coventry ribbon-manufacturer, introduced her to a circle of intellectual and literary friends. His visitors included the radicals Cobden and Bright, and such writers as Dickens and Thackeray. Mary Ann wrote articles for Bray’s Coventry Herald.

A thinly-disguised Coventry is the setting for George Eliot’s greatest novel, Middlemarch, in which the farmers and tradesmen she met here are faithfully portrayed.

Top: Michael Drayton

Above: Mary Ann Evans, alias George Eliot

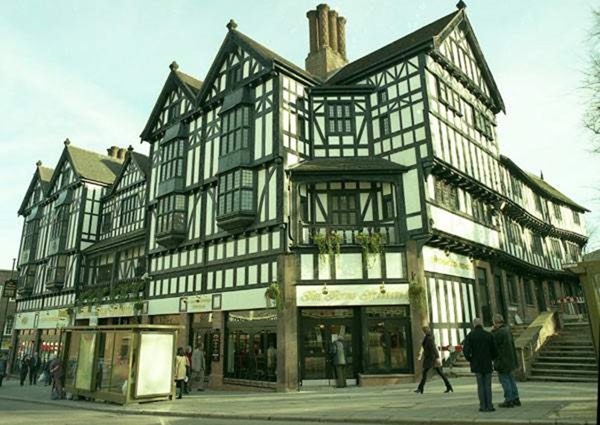

External photograph of the building – main entrance