Pub history

The Figure of Eight

This pub stands close to the well-known Gas Street canal basin, part of the city’s extensive system of canals. Built in the 18th and early 19th century, the canals later became part of a national network which crossed the country in a figure of eight, centred on Birmingham.

This pub stands close to the well-known Gas Street canal basin, part of the city’s extensive system of canals. Built in the 18th and early 19th century, the canals later became part of a national network which crossed the country in a figure of eight, centred on Birmingham.

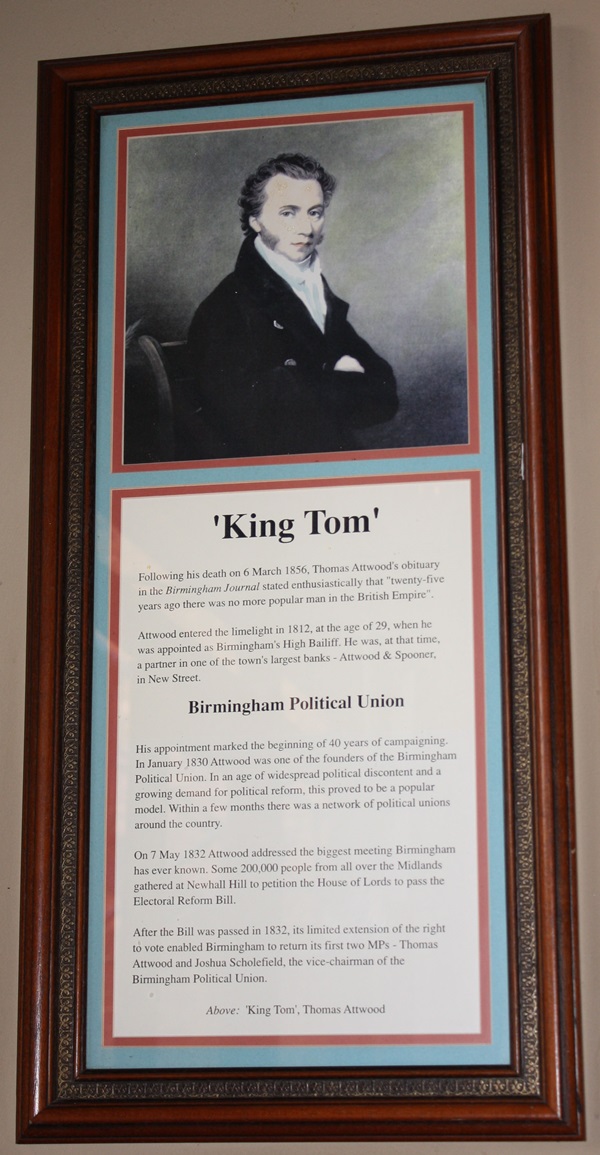

A framed print and text about Thomas Attwood, also known as King Tom

The text reads: Following his death on 6 March 1856, Thomas Attwood’s obituary in the Birmingham Journal stated enthusiastically that ‘twenty-five years ago there was no more popular man in the British Empire’.

Attwood entered the limelight in 1812, at the age of 29, when he was appointed as Birmingham’s High Bailiff. He was, at that time, a partner in one of the town’s largest banks – Attwood & Spooner in New Street.

His appointment marked the beginning of 40 years of campaigning. In January 1830, Attwood was one of the founders of the Birmingham Political Union. In an age of widespread political discontent and a growing demand for political reform, this proved to be a popular model. Within a few months, there was a network of political unions around the country.

On 7 May 1832, Attwood addressed the biggest meeting Birmingham has ever known. Some 200,000 people from all over the Midlands gathered at Newhall Hill to petition the House of Lords to pass the Electoral Reform Bill.

After the Bill was passed in 1832, its limited extension of the right to vote enabled Birmingham to return its first two MPs – Thomas Attwood and Joshua Scholefield, the vice-chairman of the Birmingham Political Union.

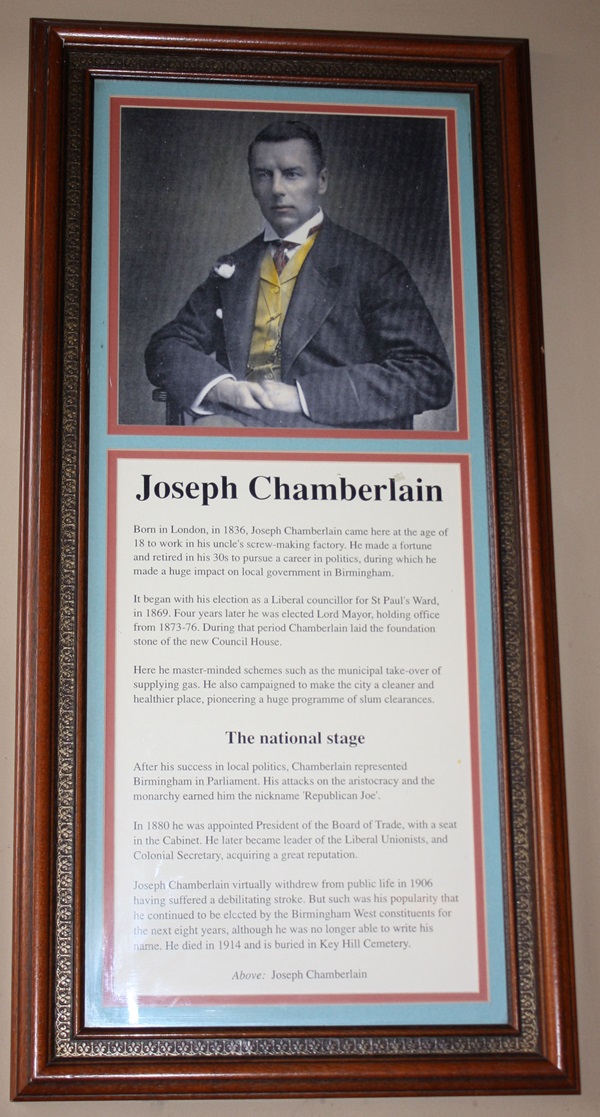

A framed photograph and text about Joseph Chamberlain

The text reads: Born in London, in 1836, Joseph Chamberlain came here at the age of 18 to work in his uncle’s screw-making factory. He made a fortune and retired in his 30s to pursue a career in politics, during which he made a huge impact on local government in Birmingham.

It began with his election as a Liberal councillor for St Paul’s Ward, in 1869. Four years later, he was elected Lord Mayor, holding office from 1873–76. During that period, Chamberlain laid the foundation stone of the new Council House.

Here, he masterminded schemes such as the municipal takeover of supplying gas. He also campaigned to make the city a cleaner and healthier place, pioneering a huge programme of slum clearances.

Alter his success in local politics, Chamberlain represented Birmingham in Parliament. His attacks on the aristocracy and the monarchy earned him the nickname ‘Republican Joe’.

In 1880, he was appointed president of the Board of Trade, with a seat in the cabinet. He later became leader of the Liberal Unionists, and Colonial Secretary, acquiring a great reputation.

Joseph Chamberlain virtually withdrew from public life in 1906, having suffered a debilitating stroke. But such was his popularity that he continued to be elected by the Birmingham West constituents for the next eight years, although he was no longer able to write his name. He died in 1914 and is buried in Key Hill Cemetery.

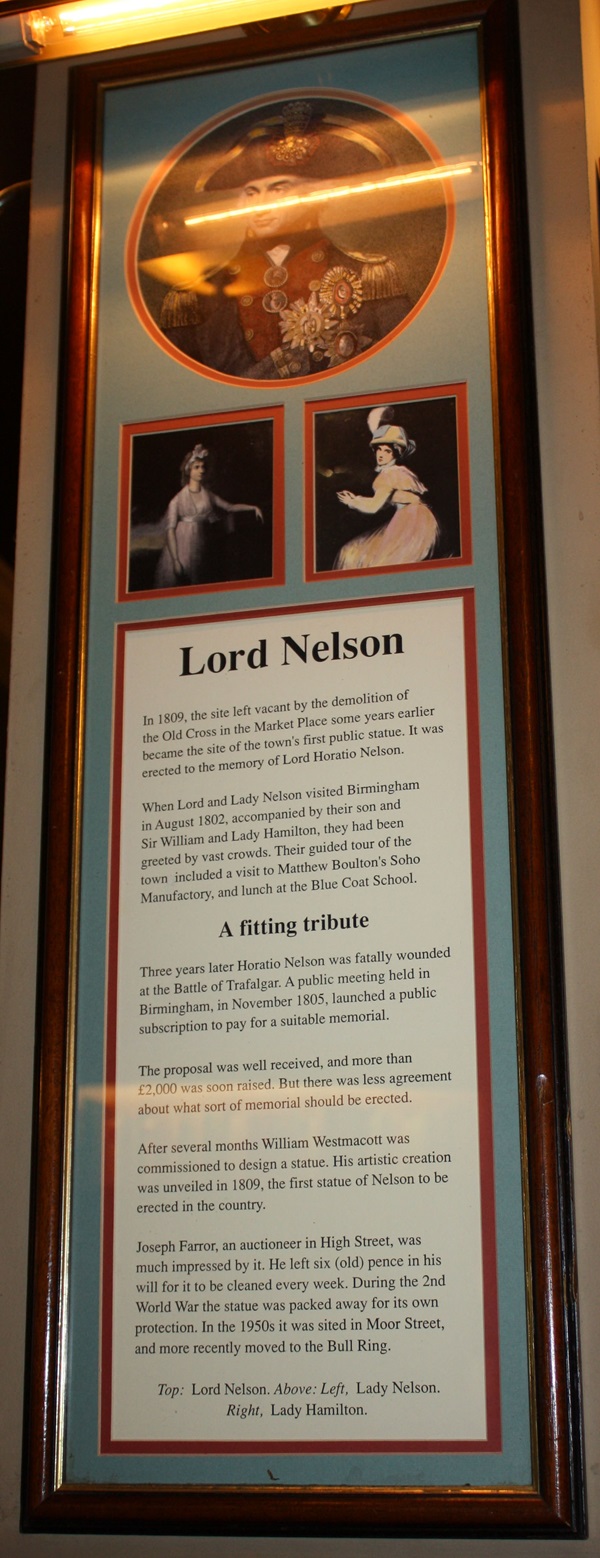

Framed photographs and text about Lord Nelson

The text reads: In 1809, the site left vacant by the demolition of the old cross in the Market Place some years earlier became the site of the town’s first public statue. It was erected to the memory of Lord Horatio Nelson.

When Lord and Lady Nelson visited Birmingham in August 1802, accompanied by their son and Sir William and Lady Hamilton, they had been greeted by vast crowds. Their guided tour of the town included a visit to Matthew Boulton’s Soho Manufactory and lunch at the Blue Coat School.

Three years later, Horatio Nelson was fatally wounded at the Battle of Trafalgar. A public meeting held in Birmingham, in November 1805, launched a public subscription to pay for a suitable memorial.

The proposal was well received, and more than £2,000 was soon raised. But there was less agreement about what sort of memorial should be erected.

After several months, William Westmacott was commissioned to design a statue. His artistic creation was unveiled in 1809, the first statue of Nelson to be erected in the country.

Joseph Farror, an auctioneer in High Street, was much impressed by it. He left six (old) pence in his will for it to be cleaned every week. During the Second World War, the statue was packed away for its own protection. In the 1950s, it was sited in Moor Street; more recently, it was moved to the Bull Ring.

Top: Lord Nelson

Above, left: Lady Nelson

Above, right: Lady Hamilton

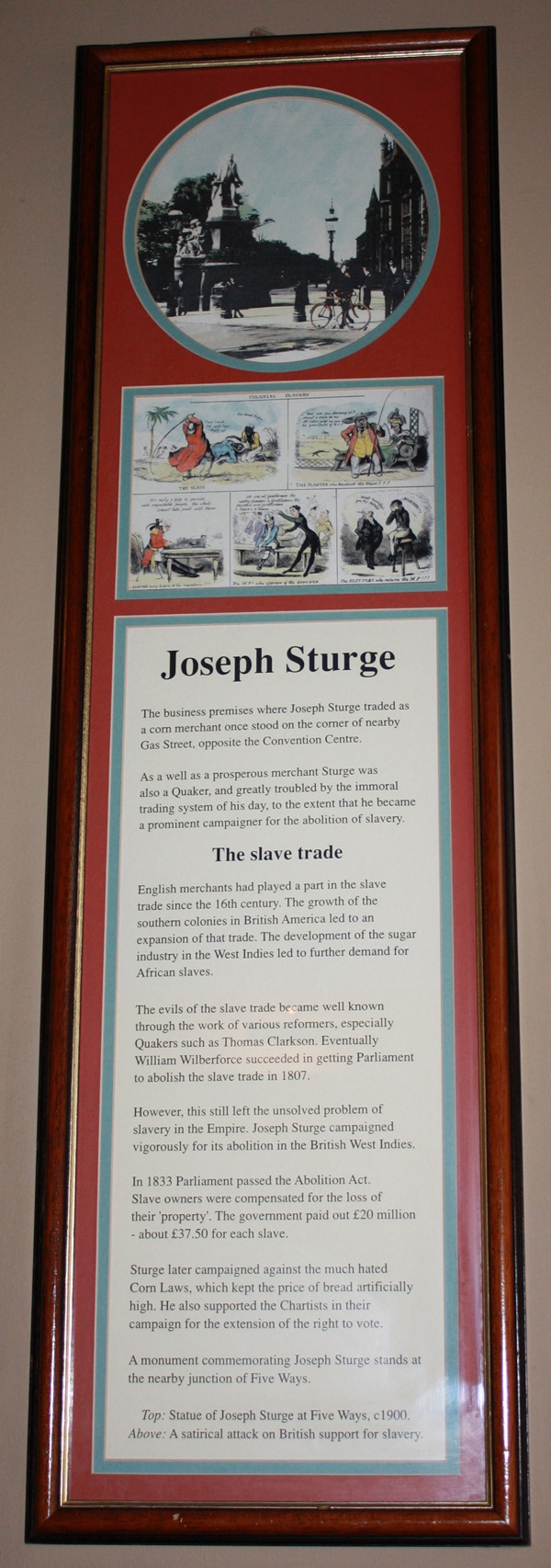

Framed prints, illustrations and text about Joseph Sturge

The text reads: The business premises where Joseph Sturge traded as a corn merchant once stood on the corner of nearby Gas Street, opposite the Convention Centre.

As a well as a prosperous merchant, Sturge was a Quaker and greatly troubled by the immoral trading system of his day, to the extent that he became a prominent campaigner for the abolition of slavery.

English merchants had played a part in the slave trade since the 16th century. The growth of the southern colonies in British America led to an expansion of that trade. The development of the sugar industry in the West Indies led to further demand for African slaves.

The evils of the slave trade became well known through the work of various reformers, especially Quakers such as Thomas Clarkson. Eventually, William Wilberforce succeeded in getting Parliament to abolish the slave trade in 1807.

However, this still left the unsolved problem of slavery in the Empire. Joseph Sturge campaigned vigorously for its abolition in the British West Indies.

In 1833, Parliament passed the Abolition Act. Slave owners were compensated for the loss of their ‘property’. The government paid out £20 million – about £37.50 for each slave.

Sturge later campaigned against the much-hated Corn Laws, which kept the price of bread artificially high. He also supported the Chartists in their campaign for the extension of the right to vote.

A monument commemorating Joseph Sturge stands at the nearby junction of Five Ways.

Top: Statue of Joseph Sturge at Five Ways, c1900

Above: A satirical attack on British support for slavery

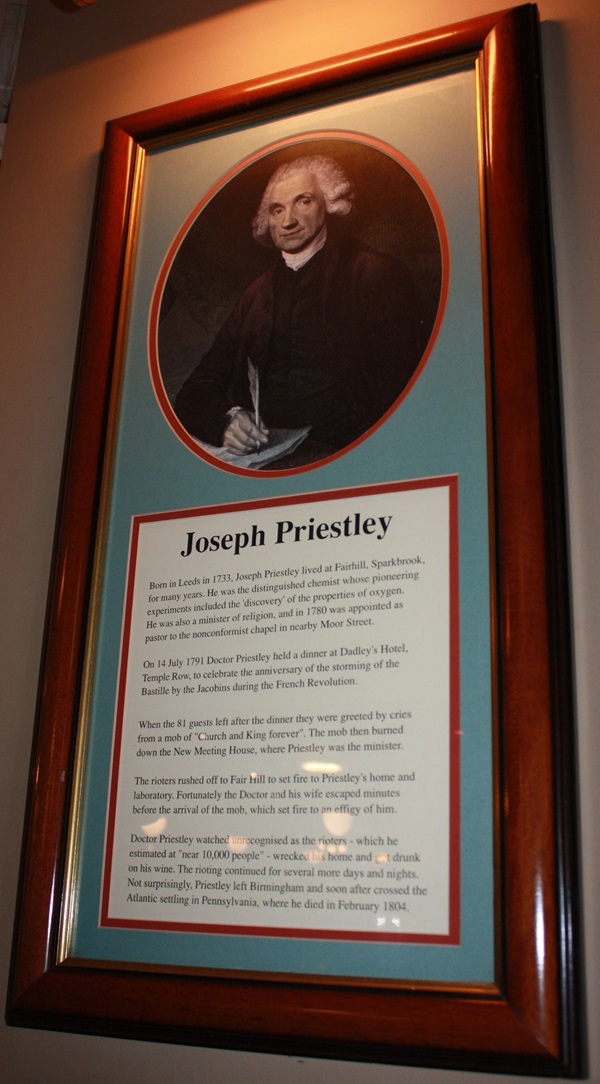

A framed print and text about Joseph Priestley

The text reads: Born in Leeds in 1733, Joseph Priestley lived at Fairhill, Sparkbrook, for many years. He was the distinguished chemist whose pioneering experiments included the ‘discovery’ of the properties of oxygen. He was also a minister of religion, and in 1780 was appointed as pastor to the nonconformist chapel in nearby Moor Street.

On 14 July 1791, Doctor Priestley held a dinner at Dadley’s Hotel, Temple Row, to celebrate the anniversary of the storming of the Bastille by the Jacobins during the French Revolution.

When the 81 guests left after the dinner, they were greeted by cries from a mob of “Church and King forever”. The mob then burned down the New Meeting House, where Priestley was the minister.

The rioters rushed off to Fair Hill to set fire to Priestley’s home and laboratory. Fortunately, the Doctor and his wife escaped minutes before the arrival of the mob, which set fire to an effigy of him.

Doctor Priestly watched unrecognised as the rioters – which he estimated at “near 10,000 people” – wrecked his home and got drunk on his wine. The rioting continued for several more days and nights. Not surprisingly, Priestley left Birmingham and soon after crossed the Atlantic, settling in Pennsylvania, where he died in February 1804.

Framed photographs from Birmingham’s history

A framed photograph of Five Ways, Birmingham, c1910

A framed photograph of the Queens and North Western Hotel, Birmingham, c1904

A framed photograph of Five Ways, Birmingham, c1908

A framed print of a Birmingham flower market

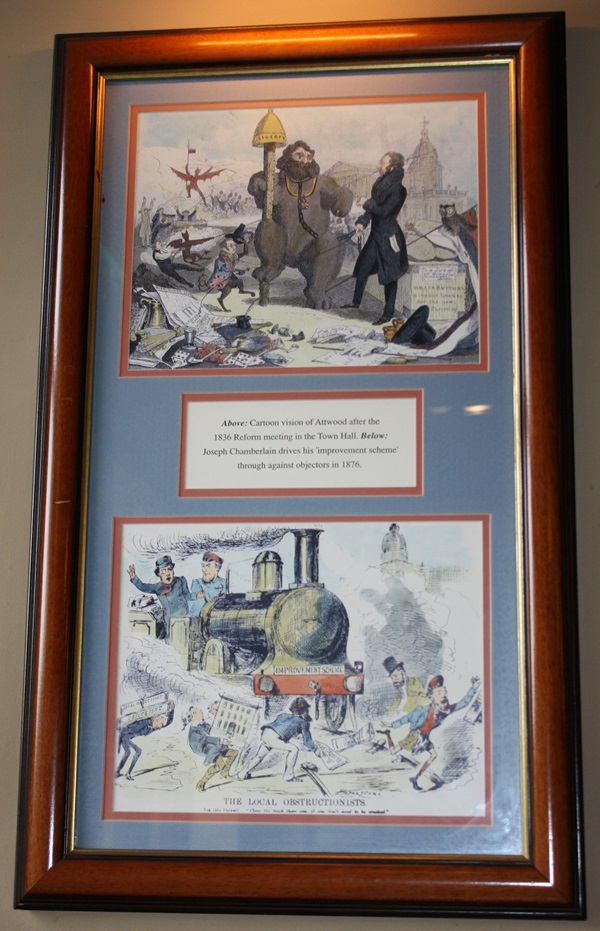

Thomas Attwood and Joseph Chamberlain depicted in framed cartoons

Above: Cartoon vision of Attwood after the 1836 Reform meeting in the Town Hall

Below: Joseph Chamberlain drives his ‘improvement scheme’ through against objectors in 1876

A framed old beer advert

A framed illustration of a rural scene

A framed print of a Birmingham canal boat

External photograph of the building – main entrance