Pub history

The Bull and Stirrup Hotel

This grade II listed building has ‘Bull and Stirrup Hotel’ inscribed on the top of the corner turret and on the George Street entrance gable. The four-storey red-brick hotel was erected in 1889, on the site of the Bull and Stirrup Inn recorded a century earlier in 1789. ‘Bull’ recalls the cattle market of Upper Northgate Street which moved to a new site, nearby, in 1850. ‘Stirrup’ recalls the stirrup cup given to a person on horseback, about to leave – ‘one for the road’.

This grade II listed building has ‘Bull and Stirrup Hotel’ inscribed on the top of the corner turret and on the George Street entrance gable. The four-storey red-brick hotel was erected in 1889, on the site of the Bull and Stirrup Inn recorded a century earlier in 1789. ‘Bull’ recalls the cattle market of Upper Northgate Street which moved to a new site, nearby, in 1850. ‘Stirrup’ recalls the stirrup cup given to a person on horseback, about to leave – ‘one for the road’.

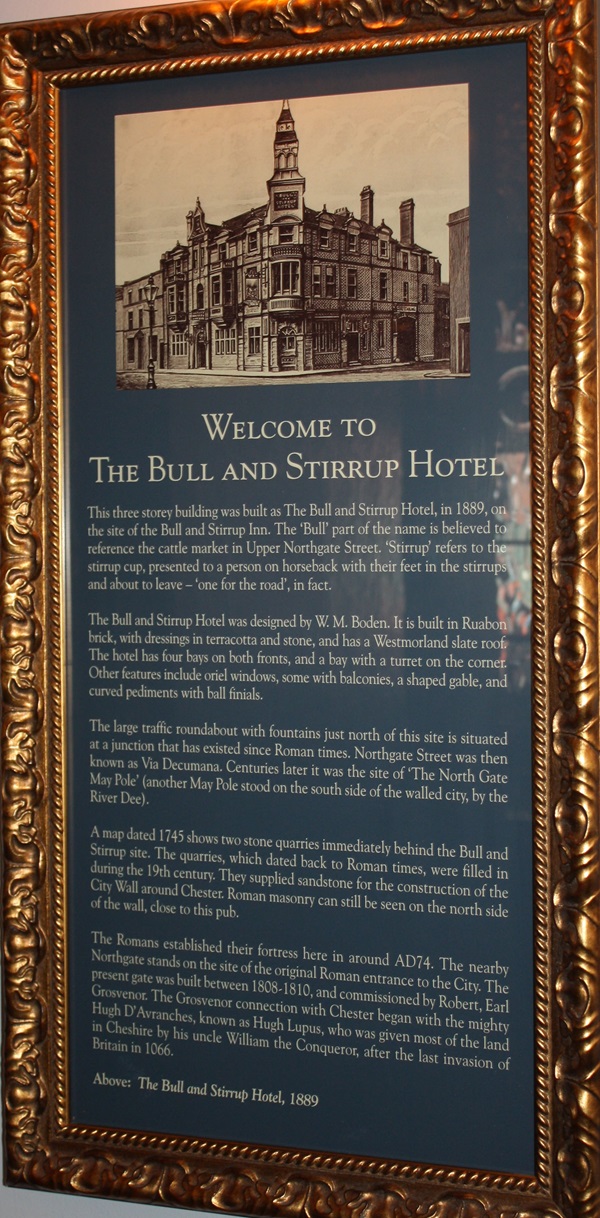

An illustration and text about The Bull and Stirrup Hotel

The text reads: This three-storey building was built as The Bull and Stirrup Hotel, in 1889, on the site of the Bull and Stirrup Inn. The ‘Bull’ part of the name is believed to reference the cattle market in Upper Northgate Street. ‘Stirrup’ refers to the stirrup cup, presented to a person on horseback with their feet in the stirrups and about to leave – ‘one for the road’, in fact.

The Bull and Stirrup Hotel was designed by WM Boden. It is built in Ruabon brick, with dressings in terracotta and stone, and has a Westmorland slate roof. The hotel has four bays on both fronts and a bay with a turret on the corner. Other features include oriel windows, some with balconies, a shaped gable, and curved pediments with ball finials.

The large traffic roundabout with fountains just north of this site is situated at a junction that has existed since Roman times. Northgate Street was then known as Via Decumana. Centuries later, it was the site of ‘The North Gate May Pole’ (another May Pole stood on the south side of the walled city, by the River Dee).

A map dated 1745 shows two stone quarries immediately behind the Bull and Stirrup site. The quarries, which dated back to Roman times, were filled in during the 19th century. They supplied sandstone for the construction of the city wall around Chester. Roman masonry can still be seen on the north side of the wall, close to this pub.

The Romans established their fortress here in around AD 74. The nearby Northgate stands on the site of the original Roman entrance to the city. The present gate was built between 1808 and 1810, and commissioned by Robert, Earl Grosvenor. The Grosvenor connection with Chester began with the mighty Hugh d’Avranches, known as Hugh Lupus, who was given most of the land in Cheshire by his uncle William the Conqueror, after the last invasion of Britain in 1066.

Above: The Bull and Stirrup Hotel, 1889

An original ceramic tile mural depicting King Edgar being rowed up the River Dee by eight other kings

The text reads: The ceramic tile mural in this lobby depicts King Edgar being rowed up the River Dee by eight other kings.

Edgar of Wessex was born c942 and became King in 959.

After his coronation, Edgar travelled north to Chester. He was met by eight sub-kings of Britain, including Kenneth, King of Scots and his son Malcolm, King of the Cumbrians.

Edgar was rowed up the River Dee to the Monastery of St John the Baptist by all eight sub-kings as a demonstration of Saxon supremacy over the Celts of England, Scotland and Wales. Under Edgar, the union of England under one dynasty was firmly established.

King Edgar the Peaceful, or the Pacific as he is sometimes known, died aged only 33 and was buried at Glastonbury Abbey.

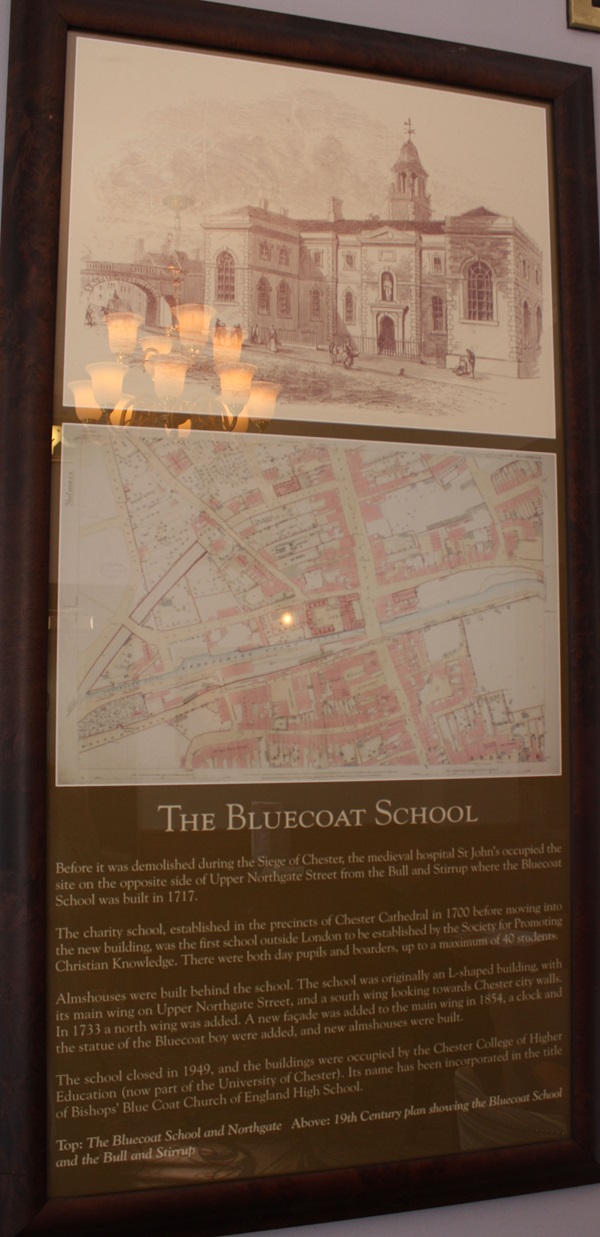

Illustrations and text about the Bluecoat School

The text reads: Before it was demolished during the Siege of Chester, the medieval hospital St John’s occupied the site on the opposite side of Upper Northgate Street from the Bull and Stirrup, where the Bluecoat School was built in 1717.

The charity school, established in the precincts of Chester Cathedral in 1700 before moving into the new building, was the first school outside London to be established by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. There were both day pupils and boarders, up to a maximum of 40 students.

Almshouses were built behind the school. The school was originally an L-shaped building, with its main wing on Upper Northgate Street, and a south wing looking towards Chester city walls. In 1733, a north wing was added. A new façade was added to the main wing in 1854, a clock and the statue of the Bluecoat boy were added, and new almshouses were built.

The school closed in 1949, and the buildings were occupied by the Chester College of Higher Education (now part of the University of Chester). Its name has been incorporated in the title of Bishops’ Blue Coat Church of England High School.

Top: The Bluecoat School and Northgate

Above: 19th-century plan showing the Bluecoat School and the Bull and Stirrup

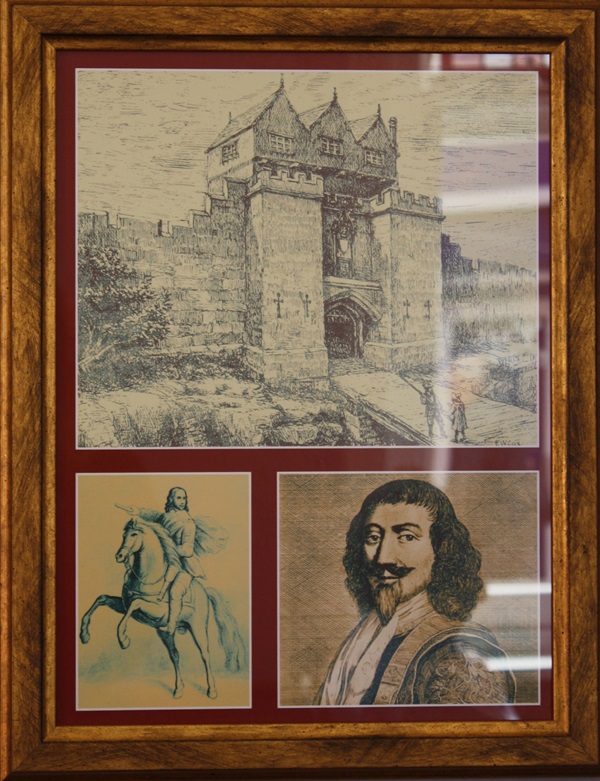

Text and prints about the Siege of Chester

The text reads: The Siege of Chester took place during the English Civil War, fought between the King and Parliament, between February 1645 and January 1646.

Chester had been a Royalist stronghold from the beginning of the war. Following his defeat at the Battle of Nantwich in January 1644, the Royalist commander Lord Byron withdrew to Chester. Although Sir William Brereton, the Parliamentarian (Roundhead) commander controlled much of Cheshire, the Royalists still held the crossing of the River Dee, which gave into north Wales.

After his defeat at Naseby, King Charles’ hopes were focused on reinforcements from Ireland or of a junction with Montrose in Scotland. Chester, the last port still in Royalist hands, was to become the key to both strategies. The Parliamentarians laid siege to the city in December 1644 and set up a close blockade.

In February 1645, Brereton launched an assault on the city. He attempted to scale the walls near to the Northgate but was repulsed.

On 20 September 1645, a force under the command of Michael Jones attacked the Royalist barricades under cover of darkness, taking the defenders totally by surprise. The Royalists were forced to fall back to the inner city.

Parliamentarian artillery began bombarding the city on 22 September. A cannon battery placed in St John’s churchyard breached the city walls near the Roman amphitheatre. Repairs made to this breach in the wall are still visible. King Charles arrived at the city from Hereford on 23 September, but after watching the defeat of his army in the battle of Rowton Heath from the Phoenix Tower, he fled to Denbigh, then to Newark.

Lord Byron refused to surrender, but as winter set in, Chester’s citizens were forced to eat cats, dogs and even rats to survive. Chester finally surrendered to the Parliamentarians in January 1646, and Sir William Brereton’s forces occupied the city on 3 February 1646.

Above: Chester in 1643

Right: The King Charles Tower, previously the Phoenix Tower, c1850

Far-right, top: the old Northgate

Far-right, bottom-left: Sir William Brereton

Far-right, bottom-right: Lord Byron

Prints and text about the greatest architect in the North West

The text reads: The architect Thomas Harrison was born in Yorkshire in 1744 and trained in Rome but practised for much of his life in Chester.

Considered the greatest architect of his day in the northwest of England, he left a legacy of fine Georgian architecture, especially public buildings and bridges. Sir Nikolas Pevsner described Harrison as ‘a local architect whose work is as good as that of any architect in London’.

Harrison was in his late thirties when he won a competition to design Skelton Bridge in Lancaster. This Classical-style bridge was one of the very first to be built without a hump in the middle. The design was later copied by John Rennie for his Waterloo and London bridges over the Thames.

In 1786, Harrison was asked to design new buildings within the grounds of Lancaster and Chester castles, projects that occupied him, together with other works, until 1815. Harrison designed a variety of other structures, one of the most important of which was the replacement of Northgate in Chester, at the suggestion of Earl Grosvenor, mayor of the city in 1807.

His final major commission was for the design of Grosvenor Bridge in Chester. The Grosvenor Bridge was the longest single-arched masonry bridge in the world at the time of its construction. Harrison died in his nearby residence, Felliot House, before the bridge was completed

Above, left: Harrison’s Chester Castle: ‘One of the most powerful moments of the Greek Revival in the whole of England’

Above, right: Chester Castle from Nun’s Gardens, 1827

Left: The Northgate, 1815

Right: Grosvenor Bridge, completed 1833

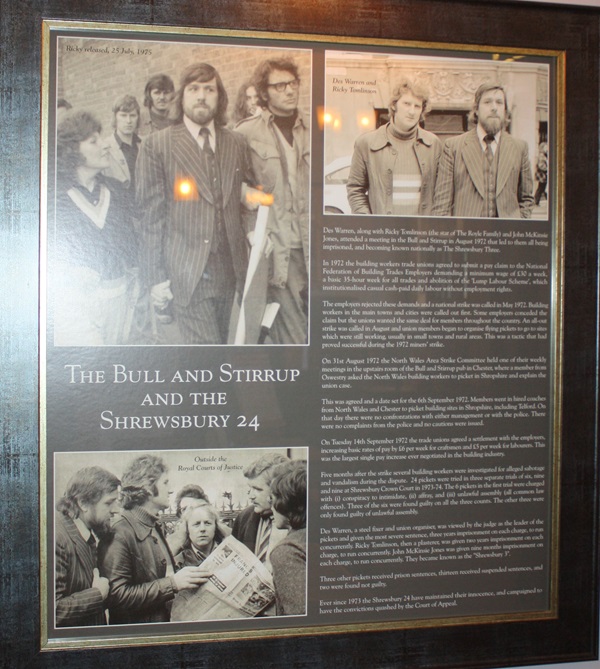

Photographs and text about the Bull and Stirrup and the Shrewsbury 24

The text reads: Des Warren, along with Ricky Tomlinson (the star of Royle Family) and John McKinsie Jones, attended a meeting in the Bull and Stirrup in August 1972 that led to them all being imprisoned, and becoming known nationally as ‘The Shrewsbury Three’.

In 1972, the building workers trade unions agreed to submit a pay claim to the National Federation of Building Trades Employers demanding a minimum wage of £30 a week, a basic 35-hour week for all trades and abolition of the ‘Lump Labour Scheme’, which institutionalised casual cash-paid daily labour without employment rights.

The employers rejected these demands, and a national strike was called in May 1972. Building workers in the main towns and cities were called out first. Some employers conceded the claim, but the unions wanted the same deal for members throughout the country. An all-out strike was called in August, and union members began to organise flying pickets to go to sites which were still working, usually in small towns and rural areas. This was a tactic that had proved successful during the 1972 miners’ strike.

On 31 August 1972, the North Wales Area Strike Committee held one of their weekly meetings in the upstairs room of the Bull and Stirrup pub in Chester, where a member from Oswestry asked the North Wales building workers to picket in Shropshire and explain the union case.

This was agreed and a date set for 6 September 1972. Members went in hired coaches from North Wales and Chester to picket building sites in Shropshire, including Telford. On that day, there were no confrontations with either management or the police. There were no complaints from the police and no cautions were issued.

On Tuesday 14 September 1972, the trade unions agreed a settlement with the employers, increasing basic rates of pay by £6 per week for craftsmen and £5 per week for labourers. This was the largest single pay increase ever negotiated in the building industry.

Five months after the strike, several building workers were investigated for alleged sabotage and vandalism during the dispute. Twenty-four pickets were tried in three separate trials of six, nine and nine at Shrewsbury Crown Court in 1973–74. The six pickets in the first trial were charged with (i) conspiracy to intimidate, (ii) affray, and (iii) unlawful assembly (all common law offences). Three of the six were found guilty on all the three counts. The other three were only found guilty of unlawful assembly.

Des Warren, a steel fixer and union organiser, was viewed by the judge as the leader of the pickets and given the most severe sentence, three years’ imprisonment on each charge, to run concurrently. Ricky Tomlinson, then a plasterer, was given two years’ imprisonment on each charge, to run concurrently. John McKinsie Jones was given nine months’ imprisonment on each charge, to run concurrently. They became known as ‘The Shrewsbury Three’.

Three other pickets received prison sentences, 13 received suspended sentences, and two were found not guilty.

Ever since 1973, the Shrewsbury 24 have maintained their innocence, and campaigned to have the convictions quashed by the Court of Appeal

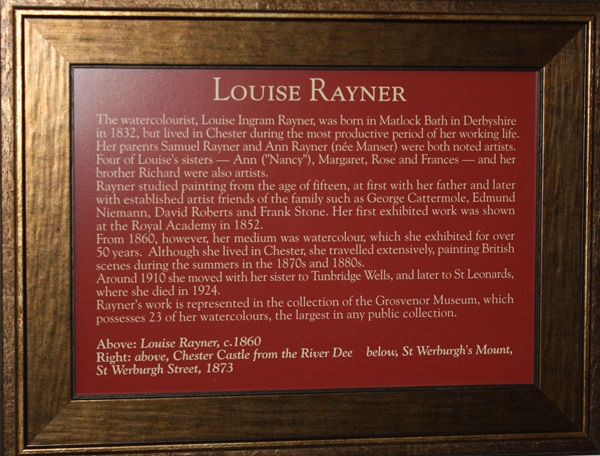

A photograph and text about Louise Rayner

The text reads: The watercolourist Louise Ingram Rayner was born in Matlock Bath in Derbyshire in 1832 but lived in Chester during the most productive period of her working life. Her parents Samuel Rayner and Ann Rayner (née Manser) were both noted artists. Four of Louise’s sisters – Ann (‘Nancy’), Margaret, Rose and Frances – and her brother Richard were also artists.

Rayner studied painting from the age of 15, at first with her father and later with established artist friends of the family such as George Cattermole, Edmund Niemann, David Roberts and Frank Stone. Her first exhibited work was shown at the Royal Academy in 1852.

From 1860, however, her medium was watercolour, which she exhibited for over 50 years. Although she lived in Chester, she travelled extensively, painting British scenes during the summers in the 1870s and 1880s.

Around 1910, she moved with her sisters to Tunbridge Wells, and later to St Leonards, where she died in 1924.

Rayner’s work is represented in the collection of Grosvenor Museum, which possesses 23 of her watercolours, the largest in any public collection.

Above: Louise Rayner, c1860

Right, above: Chester Castle from the River Dee

Right, below: St Werbugh’s Mount, St Werburgh Street, 1873

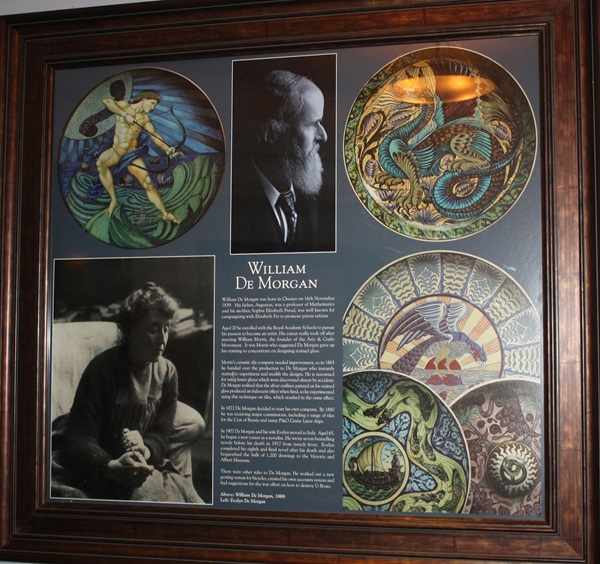

Photographs and text about William De Morgan

The text reads: William De Morgan was born in Chester on 16 November 1839. His father, Augustus, was a professor of mathematics, and his mother, Sophia Elizabeth Freud, was well known for campaigning with Elizabeth Fry to promote prison reform.

Aged 20, he enrolled with the Royal Academy Schools to pursue his passion to become an artist. His career really took off after meeting William Morris, the founder of the Arts & Crafts Movement. It was Morris who suggested De Morgan give up his training to concentrate on designing stained glass.

Morris’s ceramic tile company needed improvement, so in 1863 he handed over the production to De Morgan, who instantly started to experiment and modify the design. He is renowned for using lustre glazes, which were discovered almost by accident. De Morgan realised that silver outlines painted on his stained glass produced an iridescent effect when fired, so he experimented using the technique on tiles, which resulted in the same effect.

In 1872, De Morgan decided to start his own company. By 1880, he was receiving major commissions, including a range of tiles for the Czar of Russia and many P&O cruise liner ships.

In 1907, De Morgan and his wife Evelyn moved to Italy. Aged 65, he began a new career as a novelist. He wrote seven bestselling novels before his death in 1917 from trench fever. Evelyn completed his eighth and final novel after his death and also bequeathed the bulk of 1,200 drawings to the Victoria and Albert Museum.

There were other sides to De Morgan. He worked out a new gearing system for bicycles, created his own accounts system and had suggestions for the war effort on how to destroy U-Boats.

Above: William De Morgan, 1886

Left: Evelyn De Morgan

Illustrations, photographs and text about Chester connections

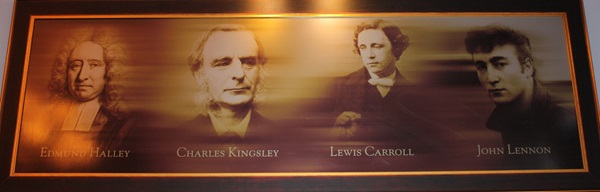

The text reads: Edmund Halley

In 1696, Edmund Halley was appointed deputy controller of the mint in Chester. It was a post he held for two years before it was abolished. Halley had begun to study comets a year earlier. He calculated that a comet which had appeared in 1682 was also the comet which was sighted in 1531 and 1607. This was later identified with a comet which had appeared in 1305, 1380 and 1456. In 1705, Halley published his prediction that the comet would reappear in 76 years, in December 1758. The comet duly appeared on Christmas Day 1758, 15 years after Halley’s death, and it was named in his honour: Halley’s Comet.

Charles Kingsley

Charles Kingsley, priest, novelist, historian and amateur naturalist, became a canon of Chester Cathedral, where he founded the Chester Society for Natural Science, Literature and Art. This society was the major inspiration behind the establishment of the Grosvenor Museum. Kingsley’s best-known novel is The Water Babies, A Fairy Tale for a Land Baby. Written in 1862–63, it was written in part as a satire in support of Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species.

Lewis Carroll

Lewis Carroll, real name Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, was born and grew up in Daresbury until he was 11 years old. He would have seen the local cheeses that were fashioned into various animal shapes – one of which was a grinning cat. The cheese was eaten from one end, so that the last piece was the grin. There was said to have been a monument to the Cheshire Cat on the site of the Chester cheese warehouse, on the banks of the River Dee, demolished in 1979 and later occupied by Copfield House.

John Lennon

John Lennon was a frequent visitor to Chester. His sister, Julia Baird, recalled, ‘During childhood, John and I used to spend a lot of time in Chester … Chester has always been in the family. We moved from Wales to Chester to Liverpool … We always thought Chester was the place to be.’ John and Julia’s grandmother and great-grandparents lived in Lower Bridge Street. As a Beatle, John later returned to Chester and played at the Riverpark Ballroom on Union Street and the Royalty Theatre in City Road. Neither of these venues exist today.

Top, left: Halley’s Comet, 1835

Left: Charles Kingsley’s sketch of himself being presented to Queen Victoria

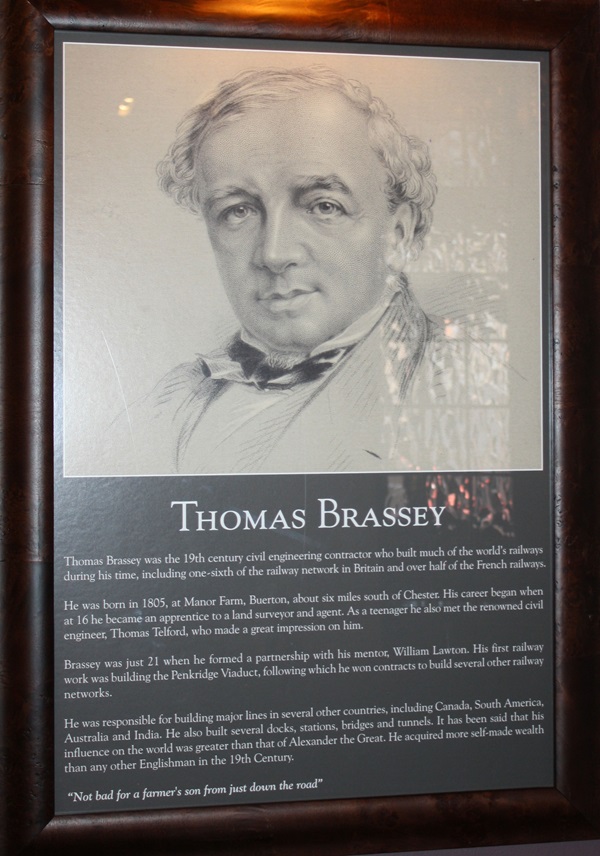

An illustration and text about Thomas Brassey

The text reads: Thomas Brassey was the 19th-century civil engineering contractor who built much of the world’s railways during his time, including one-sixth of the railway network in Britain and over half of the French railways.

He was born in 1805, at Manor Farm, Buerton, about six miles south of Chester. His career began when at 16 he became an apprentice to a land surveyor and agent. As a teenager, he also met the renowned civil engineer Thomas Telford, who made a great impression on him.

Brassey was just 21 when he formed a partnership with his mentor, William Lawton. His first railway work was building the Penkridge Viaduct, following which he won contracts to build several other railway networks.

He was responsible for building major lines in several other countries, including Canada, South America, Australia and India. He also built several docks, stations, bridges and tunnels. It has been said that his influence on the world was greater than that of Alexander the Great. He acquired more self-made wealth than any other Englishman in the 19th century.

‘Not bad for a farmer’s son from just down the road.’

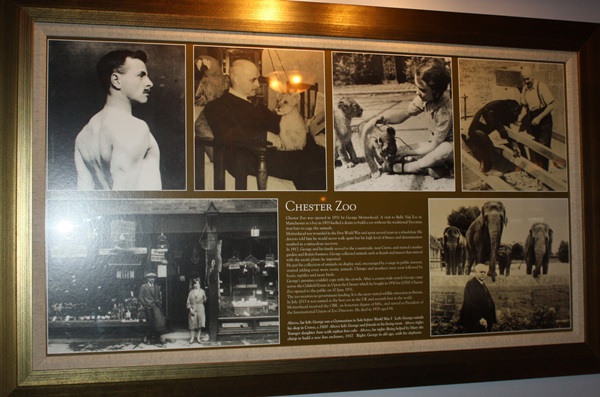

Photographs and text about Chester Zoo

The Text reads: Chester Zoo was opened in 1931 by George Mottershead. A visit to Belle Vue Zoo in Manchester as a boy in 1903 fuelled a desire to build a zoo without the traditional Victorian iron bars to cage the animals.

Mottershead was wounded in the First World War and spent several years in a wheelchair. His doctors told him he would never walk again, but his high level of fitness and determination resulted in a miraculous recovery.

In 1917, George and his family moved to the countryside, near Crewe, and started a market garden and florist’s business. George collected animals such as lizards and insects that arrived with the exotic plants he imported.

He put his collection of animals on display and, encouraged by a surge in public interest, started adding even more exotic animals. Chimps and monkeys were soon followed by bears, reptiles and more birds.

George’s premises couldn’t cope with the crowds. After a countywide search, George came across the Oakfield Estate in Upton-by-Chester, which he bought in 1930 for £3,500. Chester Zoo opened to the public on 10 June 1931.

The zoo receives no government funding. It is the most visited wildlife attraction in Britain. In July 2015, it was named as the best zoo in the UK and seventh best in the world. Mottershead received the OBE, and honorary degree of MSc, and served as President of the International Union of Zoo Directors. He died in 1978 aged 84.

Above, far left: George ran a gymnasium in Sale before World War I.

Left: George outside his shop in Crewe, c1920

Above, left: George and friends in his living room

Above, right: Younger daughter June with orphan lion cubs

Above, far right: Being helped by Mary the chimp to build a new lion enclosure, 1937

Right: George in old age, with his elephants

Text about Graham Taylor, and an example of his work

The text reads: Graham obtained a degree in three-dimensional design from Manchester Metropolitan University in 1977. From 1980 until 1993, he worked in the Kolonyama Pottery in Lesotho, Africa. From 1993 until 2000, he was head of creative arts at Machanbeng College, Lesotho. He established the Crown Studio Gallery & Potted History in Northumberland in 2001.

‘My current work focuses on the history of ceramics: Replication of artefacts: Demonstration of ancient ceramic technology: Experimental archaeology: Media presentation of ancient ceramics: Fine art projects and commissions based on ancient ceramic art.

The making techniques I employ and equipment I use are, as far as possible, the same as those used by the original makers. Above all, the act of making a piece gives me a deep sense of respect for a fellow craftsperson.’

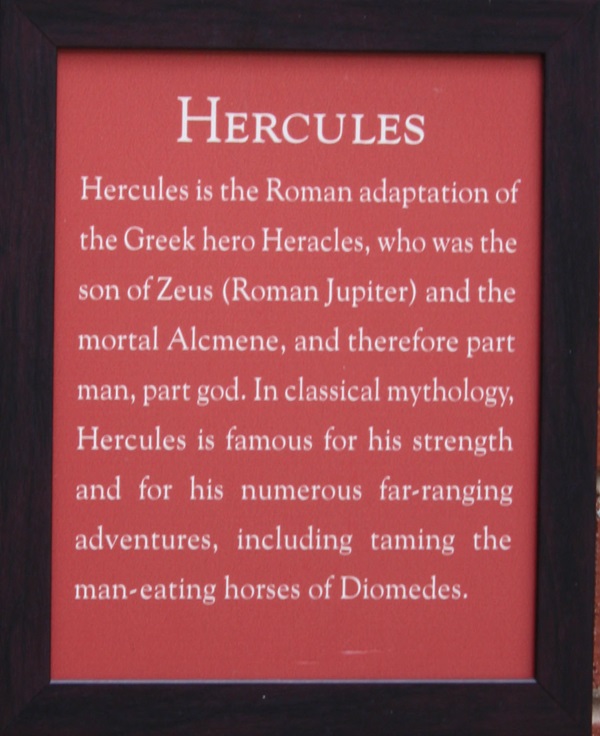

A photograph and text about Hercules

The text reads: Hercules is the Roman adaptation of the Greek hero Heracles, who is the son of Zeus (Roman Jupiter) and the mortal Alcmene, and therefore part man, part god. In classical mythology, Hercules is famous for his strength and for his numerous far-ranging adventures, including taming the man-eating horses of Diomedes.

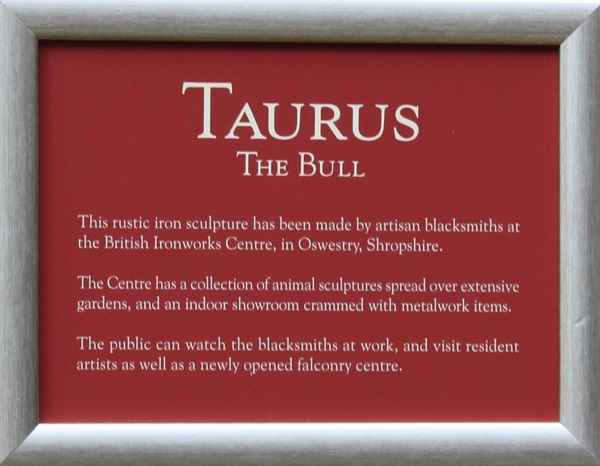

A sculpture and text about Taurus, The Bull

The text reads: This rustic iron sculpture has been made by artisan blacksmiths at the British Ironworks Centre, in Oswestry, Shropshire.

The Centre has a collection of animal sculptures spread over extensive gardens, and an indoor showroom crammed with metalwork items.

The public can watch the blacksmiths at work and visit resident artist as well as a newly opened falconry centre.

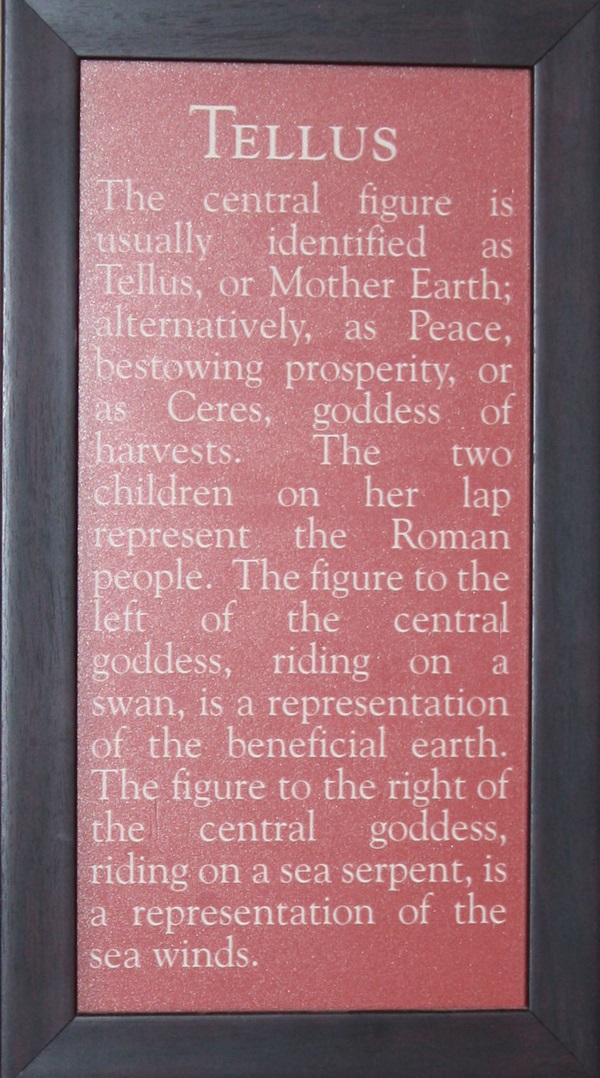

A photograph and text about Tellus (Mother Earth)

The text reads: The central figure is usually identified as Tellus, or Mother Earth; alternatively, as Peace, bestowing prosperity, or as Ceres, goddess of harvests. The two children on her lap represent the Roman people. The figure to the left of the central goddess, riding on a swan, is a representation of the beneficial earth. The figure to the right of the central goddess, riding on a sea serpent, is a representation of the sea winds.

An acrylic painting entitled The Bull and Stirrup by Diana Bernice Tackley

A montage depicting this impressive Victorian building and the wealth of historic visitor attractions within walking distance.

Bernice is an award-winning artist and winning finalist on BBC 2’s ‘Show Me The Monet’. She has lived most of her life in Cheshire and is well known for her local waterway and industrial scenes and landscapes. She was previously a freelance designer of wallpapers and furnishing fabrics, exhibiting internationally. Her paintings are in several private collections, including HRH the Duke of Kent and The Lord Lieutenant of Cheshire, David Briggs, MBE.

A window taken from the original Bull and Stirrup Hotel is now on display

This original stained-glass window is on the first floor of the hotel

The original inscribing on the top of the corner turret

External photograph of the building – main entrances

J D Wetherspoon PLC would like to thank the following people and organisations for their generous assistance in completing the display of the local history at The Bull and Stirrup Hotel:

Cheshire Archives and Local Studies

Duke Street, Chester

Chester History and Heritage

St Michael’s Church, Bridge Street Row East

The Grosvenor Museum

27, Grosvenor Street

Peter Boughton, Keeper of Art, Chester West and Cheshire Council