Pub history

The Berkeley

This was a former shopping arcade, which included Berkeley Tea Rooms. The name Berkeley has long been associated with Bristol, particularly the nearby Berkeley Square, built in the late 18th century.

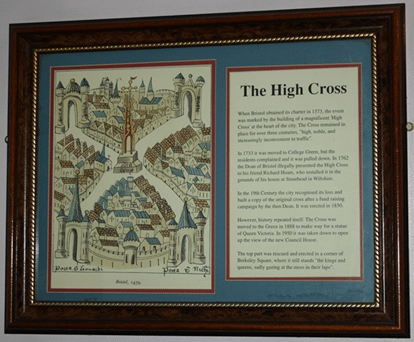

An illustration and text about the High Cross

The text reads: When Bristol obtained its charter in 1373, the event was marked by the building of a magnificent ‘High Cross’ at the heart of the city. The cross remained in place for over three centuries, ‘high, noble, and increasingly inconvenient to traffic’.

In 1733, it was moved to College Green, but the residents complained, and it was pulled down. In 1762, the Dean of Bristol illegally presented the High Cross to his friend Richard Hoare, who installed it in the grounds of his house at Stourhead in Wiltshire.

In the 19th century, the city recognised its loss and built a copy of the original cross after a fundraising campaign by the then Dean. It was erected in 1850.

However, history repeated itself. The Cross was moved to the Green in 1888 to make way for a statue of Queen Victoria. In 1959, it was taken down to open up the view of the new Council House.

The top part was rescued and erected in a corner of Berkeley Square, where it still stands, ‘the kings and queens, sadly gazing at the moss in their laps’.

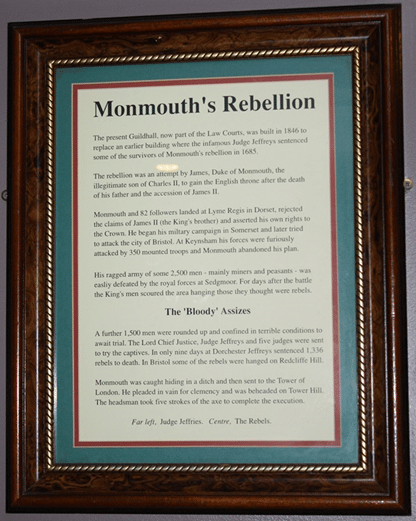

Illustrations and text about the Duke of Monmouth’s rebellion

The text reads: The present Guildhall, now part of the law courts, was built in 1846 to replace an earlier building where the infamous Judge Jeffreys sentenced some of the survivors of Monmouth’s rebellion in 1685.

The rebellion was an attempt by James, Duke of Monmouth, the illegitimate son of Charles II, to gain the English throne after the death of his father and the accession of James II.

Monmouth and 82 followers landed at Lyme Regis in Dorset, rejected the claims of James II (the King’s brother) and asserted his own rights to the Crown. He began his military campaign in Somerset and later tried to attack the city of Bristol. At Keynsham, his forces were furiously attacked by 350 mounted troops, and Monmouth abandoned his plan.

His ragged army of some 2,500 men – mainly miners and peasants – was easily defeated by the royal forces at Sedgmoor. For days after the battle, the King’s men scoured the area, hanging those they thought were rebels.

A further 1,500 men were rounded up and confined in terrible conditions to await trail. The Lord Chief Justice, Judge Jeffreys and five judges were sent to try the captives. In only nine days at Dorchester, Jeffreys sentenced 1,336 rebels to death. In Bristol, some of the rebels were hanged on Redcliffe Hill.

Monmouth was caught hiding in a ditch and then sent to the Tower of London. He pleaded in vain for clemency and was beheaded on Tower Hill. The headsman took five strokes of the axe to complete the execution.

Far left: Judge Jeffries

Centre: The Rebels

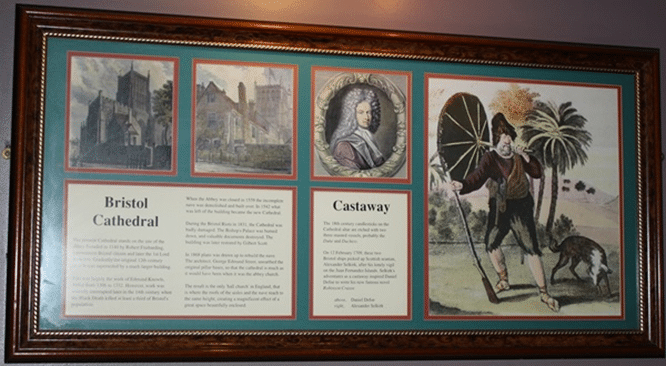

Illustrations and text about Bristol Cathedral

The text reads: The present Cathedral stands on the site of the abbey founded in 1140 by Robert Fitzharding, a prominent Bristol citizen and later the 1st Lord Berkeley. Gradually, the original 12th-century church was superseded by a much larger building.

This was largely the work of Edmund Knowle, Abbot from 1306 to 1332. However, work was severely interrupted later in the 14th century when the Black Death killed at least a third of Bristol’s population.

When the Abbey was closed in 1539, the incomplete nave was demolished and built over. In 1542, what was left of the building became the new cathedral.

During the Bristol Riots in 1831, the cathedral was badly damaged. The Bishop’s Palace was burned down and valuable documents destroyed. The building was later restored by Gilbert Scott.

In 1868, plans were drawn up to rebuild the nave. The architect, George Edmund Street, unearthed the original pillar bases, so that the cathedral is much as it would have been when it was the abbey church.

The result is the only ‘hall church’ in England – that is, where the roofs of the aisles and the nave reach to the same height, creating a magnificent effect of a great space beautifully enclosed.

The 18th-century candlesticks on the cathedral’s altar are etched with two three-masted vessels, probably the Duke and Duchess.

On 12 February 1709, these two Bristol ships picked up Scottish seaman Alexander Selkirk after his lonely vigil on the Juan Fernandez Islands. Selkirk’s adventures as a castaway inspired Daniel Defoe to write his now famous novel Robinson Crusoe.

Above: Daniel Defoe

Right: Alexander Selkirk

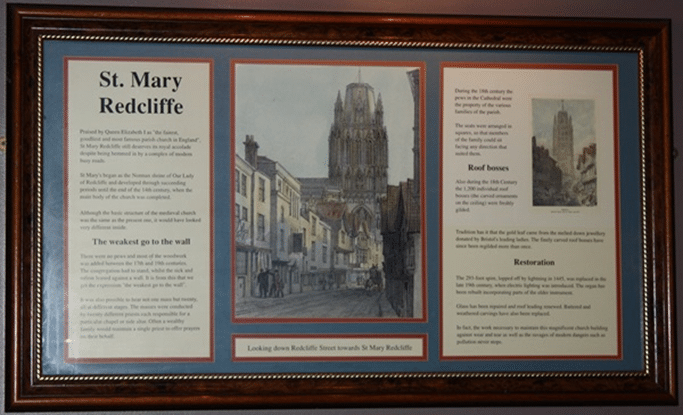

Illustrations and text about St Mary Redcliffe

The text reads: Praised by Queen Elizabeth I as ‘the fairest, goodliest and most famous parish church in England’, St Mary Redcliffe still deserves its royal accolade despite being hemmed in by a complex of modern busy roads.

St Mary’s began as the Norman shrine of Our Lady of Redcliffe and developed through succeeding periods until the end of the 14th century, when the main body of the church was completed.

Although the basic structure of the medieval church was the same as the present one, it would have looked very different inside.

There were no pews, and most of the woodwork was added between the 17th and 19th centuries. The congregation had to stand, whilst the sick and infirm leaned against a wall. It is from this that we get the expression ‘the weakest go to the wall’.

It was also possible to hear not one mass but 20, all at different stages. The masses were conducted by 20 different priests, each responsible for a particular chapel or side altar. Often a wealthy family would maintain a single priest to offer prayers on their behalf.

During the 18th century, the pews in the cathedral were the property of the various families of the parish.

The seats were arranged in squares, so that members of the family could sit facing any direction that suited them.

Also during the 18th century, the 1,200 individual roof bosses (the carved ornaments on the ceiling) were freshly gilded.

Tradition has it that the gold leaf came from the melted-down jewellery donated by Bristol’s leading ladies. The finely carved roof bosses have since been regilded more than once.

The 293-foot spire, lopped off by lightning in 1445, was replaced in the late 19th century, when electric lighting was introduced. The organ has been rebuilt, incorporating parts of the older instrument.

Glass has been repaired and roof leading renewed. Battered and weathered carvings have also been replaced.

In fact, the work necessary to maintain this magnificent church building against wear and tear as well as the ravages of modern dangers such as pollution never stops.

Illustrations and text about George Frideric Handel

The text reads: A visitor to St Mary Redcliffe during the 18th century might well have encountered George Frideric Handel working on the music for his great composition TheMessiah.

Handel was a great friend of Thomas Broughton, vicar of St Mary’s for 30 years.

Broughton is buried at the east end of the church near the ‘Handel’ window illustrating scenes from The Messiah. The window was installed in 1859 to commemorate the centenary of the death of this great composer. Handel’s output included 46 operas, as well as other orchestral, instrumental and vocal music.

Right: Handel conducting

Above: Part of The Messiah in manuscript

Text about Methodists

The text reads:Bristol was one of the most important centres of Methodism in its early days when it was still a part of the Church of England. The ‘New Room’ in Horsefair, established by John Wesley in 1739, was the first Methodist chapel in the world.

When Wesley came to this area, he joined forces with George Whitefield preaching to the people of Bristol, and in particular the miners of Kingwood.

The two preachers, full of fire and passion, were barred from most parish churches. Instead, they held open-air preaching sessions on the outskirts of the city, where spectacular scenes of conversion abounded.

Wesley later founded his own indoor church – the New Room – with sleeping quarters on the top floor for Methodist preachers visiting the city. However, Wesley only occasionally visited Bristol.

He spent much of his time travelling from one end of the country to the other.

During his ministry, John Wesley travelled 250,000 miles and preached 40,000 sermons, frequently to vast crowds. He also produced many literary works as well as founding the Methodist Magazine in 1778. Wesley’s brother Charles lived in Bristol for more than 20 years, where he wrote many of his well-known hymns.

Eventually, John Wesley and George Whitefield went their separate ways. Whitefield was appointed chaplain to the Countess of Huntingdon, whose chapel in a converted theatre stood on St Augustine’s Back, near the site of Colston Hall.

Like Wesley, Whitefield made many preaching tours throughout England, Scotland and Wales. He also undertook seven visits to American, setting out for the last time in 1769. He died near Boston the following year.

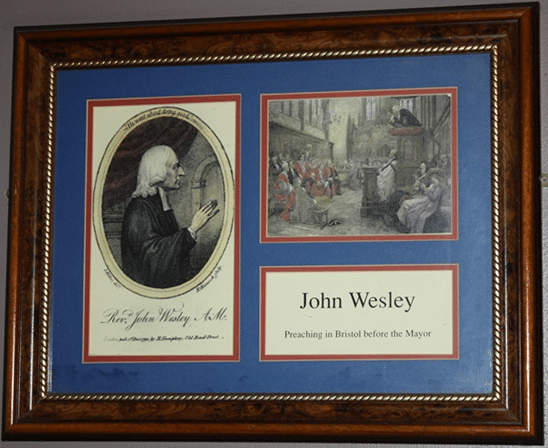

Illustrations of John Wesley preaching in Bristol before the mayor

Text about the Bristol Riots

The text reads: The riots in the autumn of 1831 were a brief and destructive period in Bristol’s history. During this turbulent episode, many people died, and much of Queen Square – including the Customs House and the Mansion House – was burned down, as was the Bishop’s Palace.

The protest was sparked off by the issue of voting reform, a concern widespread throughout England, and delays in passing the Reform Bill.

Matters were made much worse by the arrival of Sir Charles Wetherell, the ‘Recorder of Bristol’, who was an eccentric and also a staunch opponent of political reform.

Rioting broke out on 29 October. A contemporary account gives some idea of what took place:

‘but a short distance from us was Bridewell, likewise in flames; then came Queen Square.’

The passage continues:

‘Queen Square, which I must fail in attempting to describe: the flames towering to the skies, and the long volume of smoke curling in a thousand varied forms; now and then balls of fire would be blown into the air and carried a considerable distance, while the reflection of the light on the trees, various steeples and distant landscape formed a scene terrific indeed, but at the same time beautifully awful.’

The mayor, Charles Pinney, read the Riot Act, and troops, led by Lt Colonel Brereton, were called in to restore order. A number of rioters were killed.

Not long after the riots, both men stood trail. Charles Pinney was acquitted, but Colonel Brereton shot himself before his court martial was able to deliver its verdict.

Some of the rioters were hanged, while many more were either imprisoned or transported.

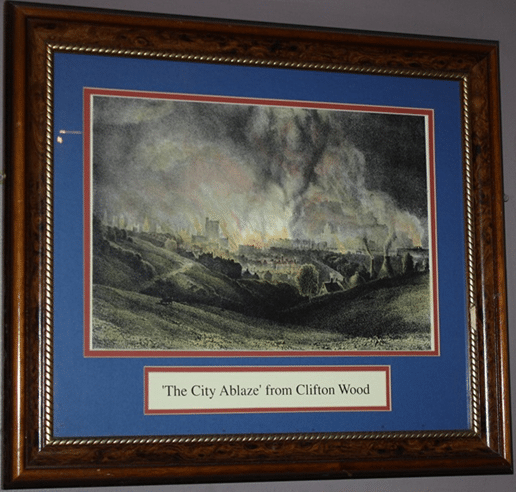

An illustration of ‘The City Ablaze’ from Clifton Wood

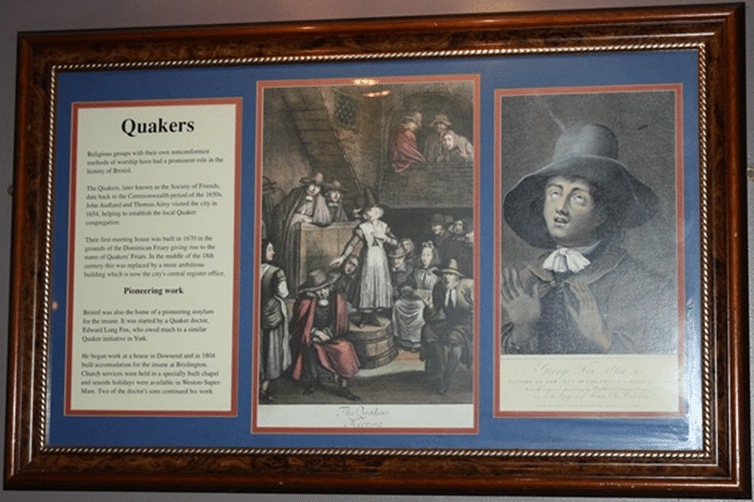

Illustrations and text about Quakers

The text reads: Religious groups with their own nonconformist methods of worship have had a prominent role in the history of Bristol.

The Quakers, later known as the Society of Friends, date back to the Commonwealth period of the 1650s. John Audland and Thomas Airey visited the city in 1654, helping to establish the local Quaker congregation.

Their first meeting house was built in 1670 in the grounds of the Dominican friary, giving rise to the name Quakers’ Friars. In the middle of the 18th century, this was replaced by a more ambitious building which is now the city’s central register office.

Bristol was also the home of a pioneering asylum for the insane. It was started by a Quaker doctor, Edward Long Fox, who owed much to a similar Quaker initiative in York.

He began work at a house in Downend and in 1804 built accommodation for the insane at Brislington. Church services were held in a specially built chapel, and seaside holidays were available in Weston-super-Mare. Two of the doctor’s sons continued his work.

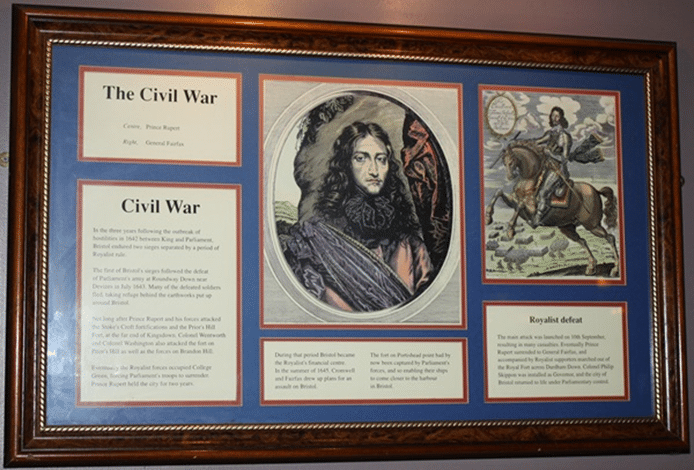

Illustrations and text about the Civil War

The text reads: In the three years following the outbreak of hostilities in 1642 between King and Parliament, Bristol endured two sieges separated by a period of Royalist rule.

The first of Bristol’s sieges followed the defeat of Parliament’s army at Roundway Down near Devizes in July 1643. Many of the defeated soldiers fled, taking refuge behind the earthworks put up around Bristol.

Not long after, Prince Rupert and his forces attacked the Stoke’s Croft fortifications and the Prior’s Hill Fort, at the far end of Kingsdown. Colonel Wentworth and Colonel Washington also attacked the fort on Prior’s Hill as well as the forces on Brandon Hill.

Eventually, the Royalist forces occupied College Green, forcing Parliament’s troops to surrender. Prince Rupert held the city for two years.

During that period, Bristol became the Royalists’ financial centre. In the summer of 1645, Cromwell and Fairfax drew up plans for an assault on Bristol.

The fort on Portishead point had by now been captured by Parliament’s forces, and so enabling their ships to come closer to the harbour in Bristol.

The main attack was launched on 10 September, resulting in many casualties. Eventually, Prince Rupert surrendered to General Fairfax, and accompanied by Royalist supporters marched out of the Royal Fort across Durdham Down. Colonel Philip Skippon was installed as Governor, and the city of Bristol returned to life under Parliamentary control.

Centre: Prince Rupert

Right: General Fairfax

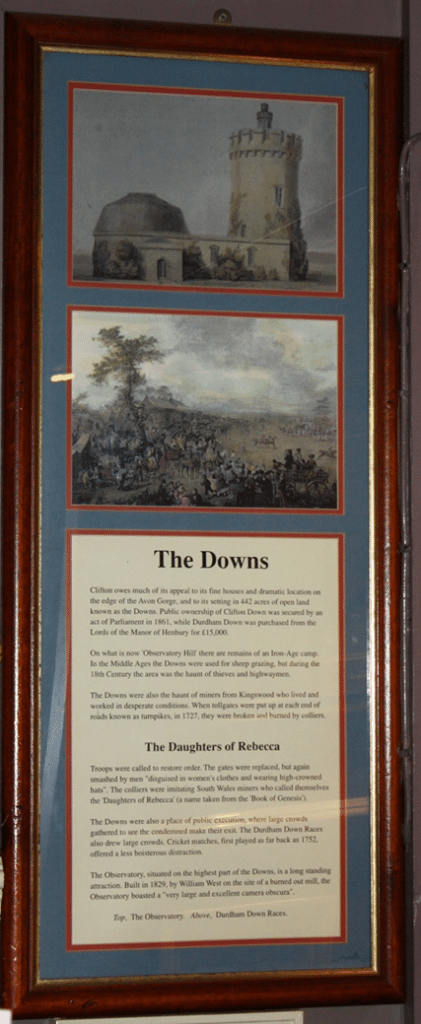

Prints and text about the Downs

The text reads: Clifton owes much of its appeal to its fine houses and dramatic location on the edge of the Avon Gorge, and to its setting in 442 acres of open land known as the Downs. Public ownership of Clifton Down was secured by an Act of Parliament in 1861, while Durdham Down was purchased from the Lords of the Manor of Henbury for £15,000.

On what is now Observatory Hill, there are remains of an Iron Age camp. In the Middle Ages, the Downs were used for sheep grazing, but during the 18th century the area was the haunt of thieves and highwaymen.

The Downs were also the haunt of miners from Kingswood, who lived and worked in desperate conditions. When tollgates were put up at each end of roads known as turnpikes, in 1727, they were broken and burned by colliers.

Troops were called to restore order. The gates were replaced, but again smashed by men ‘disguised in women’s clothes and wearing high-crowned hats’. The colliers were imitating South Wales miners who called themselves the ‘Daughters of Rebecca’ (a name taken from the ‘Book of Genesis’).

The Downs were also a place of public execution, where large crowds gathered to see the condemned make their exit. The Durdham Down Races also drew large crowds. Cricket matches, first played as far back as 1752, offered a less boisterous distraction.

The Observatory, situated on the highest part of the Downs, is a long-standing attraction. Built in 1829, by William West on the site of a burned-out mill, the Observatory boasted a ‘very large and excellent camera obscura’.

Top: The Observatory

Above: Durdham Down Races

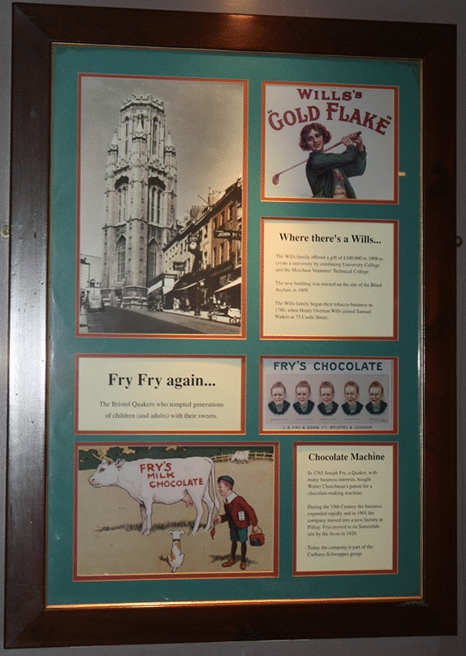

Prints, illustrations and text about Fry’s chocolate

The text reads: The Wills family offered a gift of £100,000 in 1908 to create a university by combining University College and the Merchant Venturers’ Technical College.

The new building was erected on the site of the Blind Asylum in 1909.

The Wills family began their tobacco business in 1786, when Henry Overton Wills joined Samuel Watkin at 73 Castle Street.

In 1765, Joseph Fry, a Quaker with many business interests, bought Walter Churchman’s patent for a chocolate-making machine.

During the 19th century, the business expanded rapidly, and in 1901 the company moved into a new factory at Pithay. Fry’s moved to its Somerdale site by the Avon in 1920.

Today, the company is part of the Cadbury Schweppes group.

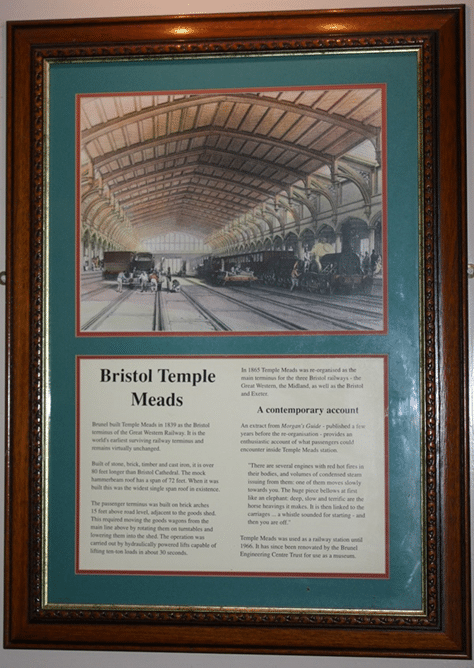

A print and text about Bristol Temple Meads

The text reads: Brunel built Temple Meads in 1839 as the Bristol terminus of the Great Western Railway. It is the world’s earliest surviving railway terminus and remains virtually unchanged.

Built of stone, brick, timber and cast iron, it is over 80 feet longer than Bristol Cathedral. The mock hammerbeam roof has a span of 72 feet. When it was built, this was the widest single-span roof in existence.

The passenger terminus was built on brick arches 15 feet above road level, adjacent to the goods shed. This required moving the goods wagons from the main line above by rotating them on turntables and lowering them into the shed. The operation was carried out by hydraulically powered lifts capable of lifting 10-ton loads in about 30 seconds.

In 1865, Temple Meads was reorganised as the main terminus for the three Bristol railways – the Great Western, the Midland, and the Bristol and Exeter.

An extract from Morgan’s Guide – published a few years before the reorganisation – provides an enthusiastic account of what passengers could encounter inside Temple Meads station:

‘There are several engines with red hot fires in their bodies, and volumes of condensed steam issuing from them: one of them moves slowly towards you. The huge piece bellows at first like an elephant: deep, slow and terrific are the horse heavings it makes. It is then linked to the carriages … a whistle sounded for starting – and then you are off.’

Temple Meads was used as a railway station until 1966. It has since been renovated by the Brunel Engineering Centre Trust for use as a museum.

Prints of a tramway centre, Bristol, c1905

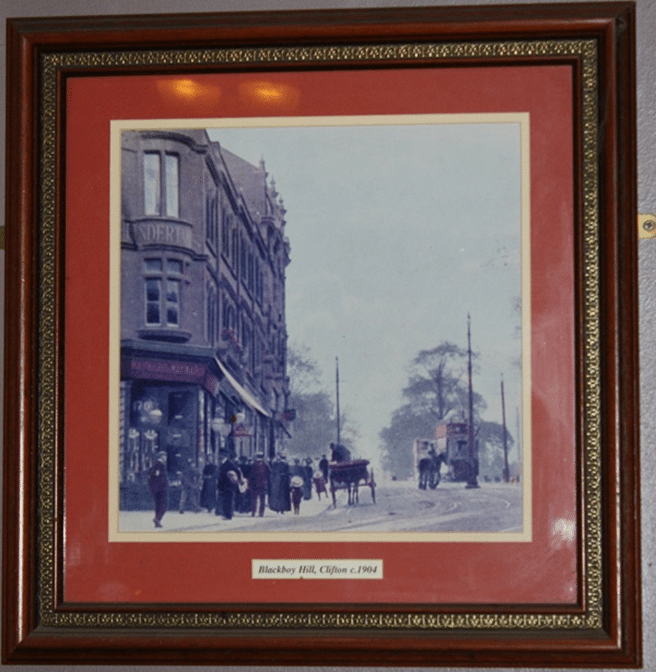

A print of Blackboy Hill, Clifton, c1904

A print of Wine Street, Bristol, c1905

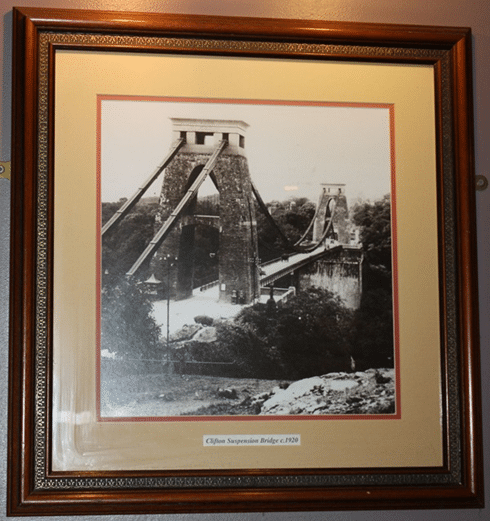

A photograph of Clifton Suspension Bridge, c1920

A photograph of Bristol Bridge, c1905

A photograph of the Royal Promenade and Triangle, Clifton, c1910

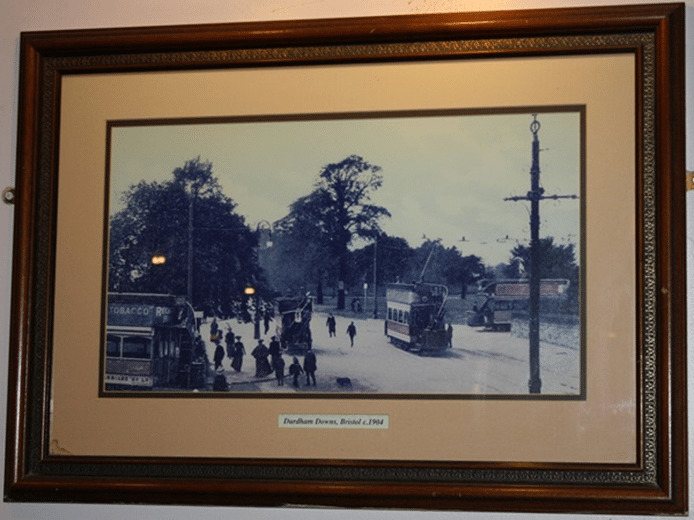

A photograph of Durdham Downs, Bristol, c1904

A photograph of The Docks, Bristol, c1910

A photograph of the tram terminus, Redlands, c1908

Modern artwork by local artist Sarah Crapper, born 1965

Sarah Crapper studied art and design at Harrogate College of Art, from 1986–91. She attended Bristol Polytechnic and has a BA in fine art and a postgraduate diploma in computer illustration.

Sarah has lived in Bristol ever since, working as an illustrator, art director and freelance artist. She has been included in more than 30 exhibitions since 1990, mainly in the Bristol area. Her Bristol exhibitions include ‘The Guild Christmas Exhibition’ at the Bristol Guild of Applied Art and ‘The Corporate Art Show’ at The Picture Business.