Pub history

The Benjamin Huntsman

This is named after the inventor of the famous crucible steel-making process which made Sheffield famous. The pub now faces Cambridge Street, originally called Coalpit Lane, which was renamed when the Duke of Cambridge, in 1857, laid the foundation stone of the nearby Crimean War monument.

This is named after the inventor of the famous crucible steel-making process which made Sheffield famous. The pub now faces Cambridge Street, originally called Coalpit Lane, which was renamed when the Duke of Cambridge, in 1857, laid the foundation stone of the nearby Crimean War monument.

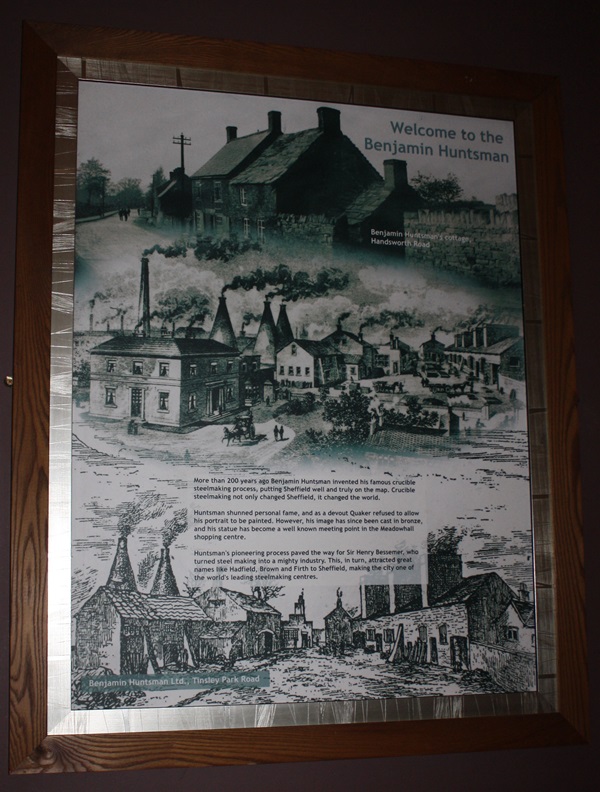

Framed illustrations and text about Benjamin Huntsman

The text reads: More than 200 years ago, Benjamin Huntsman invented his famous crucible steel-making process, putting Sheffield well and truly on the map. Crucible steel-making not only changed Sheffield; it changed the world.

Huntsman shunned personal fame, and as a devout Quaker refused to allow his portrait to be painted. However, his image has since been cast in bronze, and his statue has become a well-known meeting point in the Meadowhall shopping centre.

Huntsman’s pioneering process paved the way for Sir Henry Bessemer, who turned steel-making into a mighty industry. This, in turn, attracted great names like Hadfield, Brown and Firth to Sheffield, making the city one of the world’s leading steel-making centres.

Above: Benjamin Huntsman’s cottage, Handsworth Road

Below: Benjamin Huntsman Ltd., Tinsley Park Road

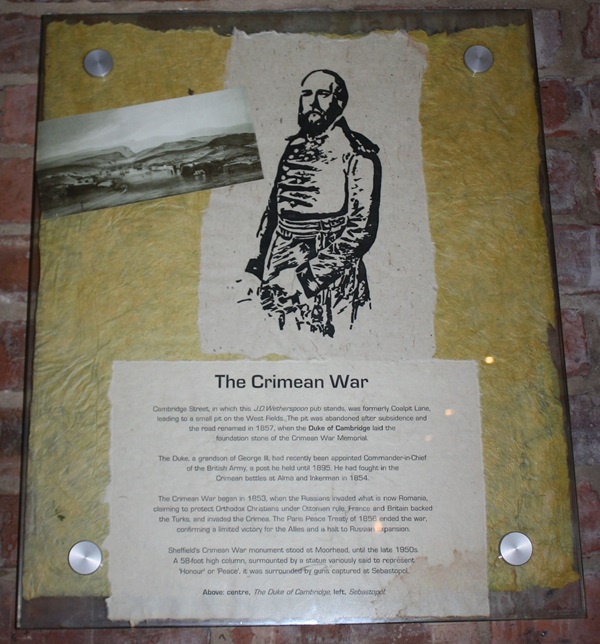

A framed print of the Duke of Cambridge and text about the Crimean War

The text reads: Cambridge Street, in which this J D Wetherspoon pub stands, was formerly Coalpit Lane, leading to a small pit on the West Fields. The pit was abandoned after subsidence and the road renamed in 1857, when the Duke of Cambridge laid the foundation stone of the Crimean War Memorial.

The Duke, a grandson of George III, had recently been appointed commander-in-chief of the British Army, a post he held until 1895. He had fought in the Crimean battles at Alma and Inkerman in 1854.

The Crimean War began in 1853, when the Russians invaded what is now Romania, claiming to protect Orthodox Christians under Ottoman rule. France and Britain backed the Turks and invaded the Crimea. The Paris Peace Treaty of 1856 ended the war, confirming a limited victory for the Allies and a halt to Russian expansion.

Sheffield’s Crimean War monument stood at Moorhead until the late 1950s. A 58-foot-high column, surmounted by a statue variously said to represent ‘honour’ or ‘peace’, it was surrounded by guns captured at Sebastopol.

Above, centre: The Duke of Cambridge

Above, left: Sebastopol

Framed photographs, illustrations and text about the Cole brothers

The text reads: Fargate, meaning the further way, was once the main route to the south. Until the 1880s, it remained a very narrow street, although by then the development of retail shops was well established. At the end of the 19th century, the largest of these was the three Cole brothers’ drapery shop. Founded in 1869, it was one of Sheffield’s earliest department stores. From the first building, on the corner of Church Street, Cole Brothers gradually extended down Fargate.

Coles’ Corner was a famous meeting place until 1963, when Cole Brothers moved to a new site, opposite this Wetherspoon pub, and the Fargate premises were demolished. The Cambridge Street site had previously been occupied by the Albert Hall, as well as a pub known as the Canbridge Arms, formerly the Yellow Lion.

The Albert Hall opened in 1873, as a venue for large orchestral and choral concerts. Short films were shown here around the turn of the century, in the intervals of other entertainment. From the time of the First World War, it was used almost exclusively as a cinema until its destruction by fire in 1937.

Left: Cole Brothers, 1867

Centre: Albert Hall

Right: Farngate

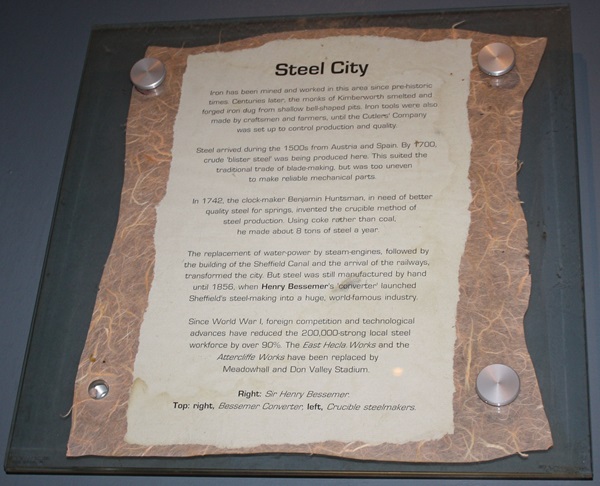

Framed photographs, illustrations and text about the Steel City

The text reads: Iron has been mined and worked in this area since prehistoric times. Centuries later, the monks of Kimberworth smelted and forged iron dug from shallow bell-shaped pits. Iron tools were also made by craftsmen and farmers, until the Cutlers’ Company was set up to control production and quality.

Steel arrived during the 1500s from Austria and Spain. By 1700, crude ‘blister steel’ was being produced here. This suited the traditional trade of blade-making but was too uneven to make reliable mechanical parts.

In 1742, the clockmaker Benjamin Huntsman, in need of better-quality steel for springs, invented the crucible method of steel production. Using coke rather than coal, he made about 8 tons of steel a year.

The replacement of waterpower by steam engines, followed by the building of the Sheffield Canal and the arrival of the railways, transformed the city. But steel was still manufactured by hand until 1856, when Henry Bessemer’s ‘converter’ launched Sheffield’s steel-making into a huge, world-famous industry.

Since World War I, foreign competition and technological advances have reduced the 200,000-strong local steel workforce by over 90%. The East Hecla Works and the Attercliffe Works have been replaced by Meadowhall and Don Valley Stadium.

Right: Sir Henry Bessemer

Top, right: Bessemer Converter

Top, left: Crucible steelmakers

A steel-inspired sculpture which features in the pub’s entrance

A mirrored sculpture inside The Benjamin Huntsman, accompanied by a plaque

A painting entitled Casting Crucible Steel Ingots, 1918

Photographs showing First World War munitions and Sheffield steel castings and forgings

Photographs showing the theatres of Sheffield

Framed prints of the steelworks

External photograph of the building – main entrance

Extract from Wetherspoon News Spring 2019

The text reads: One of our pubs in Sheffield, which opened in November 1999, is named after the inventor of the famous crucible steel-making process which made the city famous.

Born in 1704, in Lincolnshire, Benjamin Huntsman invented crucible (or cast) steel – this was more uniform and more pure than any steel previously produced, a significant development at that time.

A clock and instrument maker, he produced steel, at his plant in Sheffield, for clock and watch springs.