Pub history

The Assembly Rooms

Built in the late 17th century, when Epsom developed into a leading health spa, the assembly rooms housed a draper’s shop and building society for most of the 20th century. It is now a Wetherspoon pub, bearing its original name.

Built in the late 17th century, when Epsom developed into a leading health spa, the assembly rooms housed a draper’s shop and building society for most of the 20th century. It is now a Wetherspoon pub, bearing its original name.

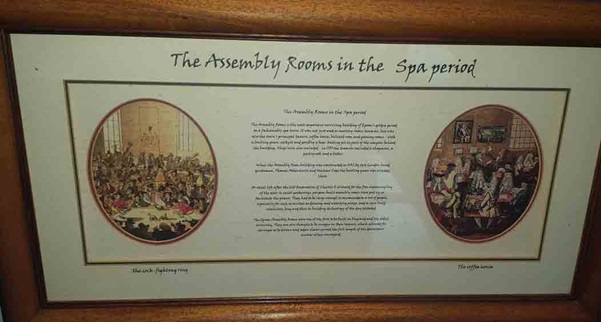

Illustrations and text about the Assembly Rooms in the spa period

The text reads:

The Assembly Rooms is the most important surviving building of Epsom’s golden period as a fashionable spa town. It was not just used as meeting rooms, however, but was also the town’s principal tavern, coffee house, billiard room and gaming room – with a bowling green, cockpit and possibly a bear-baiting pit as part of the complex behind the building. Shops were also included – in 1735, the tenants included a chapman, a pastry-cook and a baker.

When the Assembly Rooms building was constructed in 1692 by two London-based gentlemen, Thomas Ashenhurst and Michael Cope, the bowling green was already there.

As social life after the 1660 restoration of Charles II allowed for the free intermingling of the sexes in social gatherings, purpose-built assembly rooms were put up to facilitate the process. They had to be large enough to accommodate a lot of people, especially for such activities as dancing and watching plays, and so were built relatively long and thin as building technology of the day dictated.

The Epsom Assembly Rooms were one of the first to be built in England, and are the oldest surviving. They are also thought to be unique in their layout, which allowed for carriages to be driven and sedan chairs carried the full length of the downstairs central alley/courtyard.

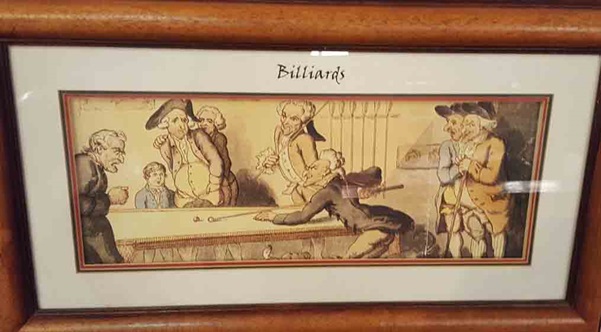

An illustration of billiards

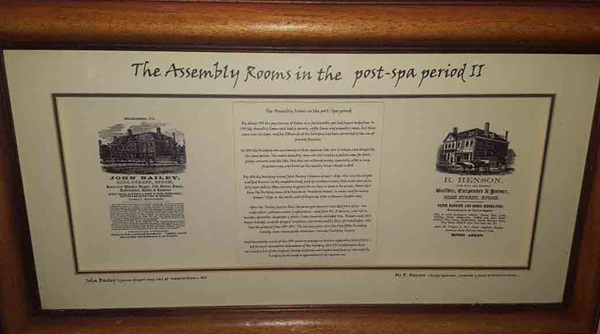

Illustrations and text about the Assembly Rooms in the post-spa period

The text reads: By about 1730, the popularity of Epsom as a fashionable spa had begun to decline. In 1755, the Assembly Rooms still had a tavern, coffee house and assembly rooms, but there were now six shops, and by 1790 much of the building had been converted to the use of private families.

In 1814, the building was auctioned as three separate lots, two of which were bought by the same person. The main assembly room was still used as a public room for balls, plays, concerts and the like, but this use withered away, especially after a large function room was built at the nearby Kings Head in 1838.

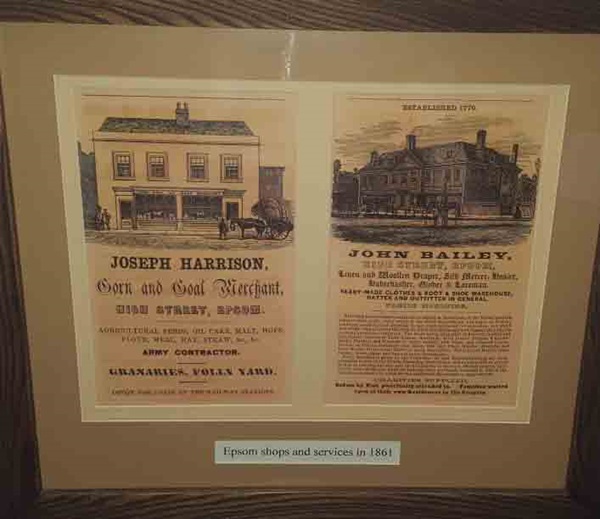

By 1860, the building housed John Bailey’s famous draper’s shop. This was the largest and best known in the neighbourhood, and its customers came from miles around to buy their fabric, often having to queue for an hour or more to be served. About this time, the building came to be known as Waterloo House, a name used for many draper’s shops in the southeast of England, after a famous London shop.

After Mr Bailey died in 1862, the principal tenants included John Gray – an undertaker, cabinet-maker and upholsterer – and then Mr R Henson, who was a builder, decorator, carpenter and joiner. Later tenants included Win. Bristow and John Major Oldridge, and the draper’s tradition was continued by Ely’s of Wimbledon, who had the premises from 1953–64. The last occupiers were the Post Office Building Society, later renamed the National Countries Building Society.

Unfortunately, many of the 20th century changes in tenure, especially that of Ely’s, led to major structural alterations of the building, but J D Wetherspoon have recreated much of the of the original façade and internal layout and finally returned the building to the modern equivalent of its original use.

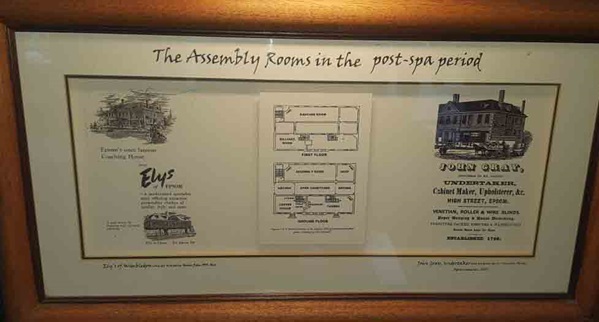

Illustrations of The Assembly Rooms in the post-spa period, including the floor plans

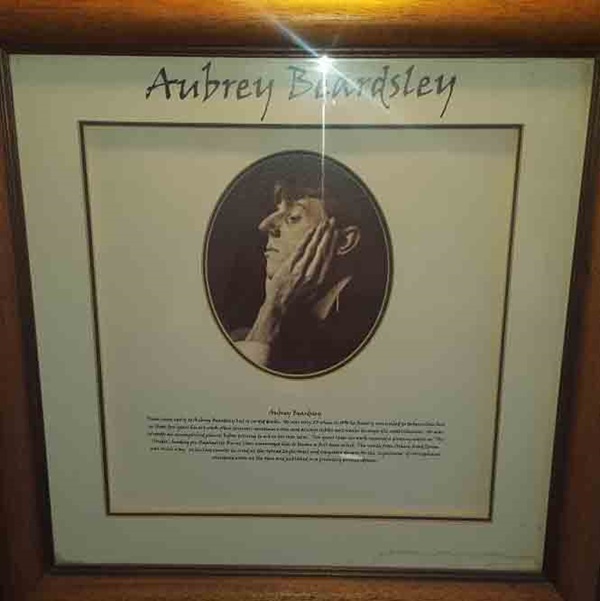

A photograph and text about Aubrey Beardsley

The text reads: Fame came early to Aubrey Beardsley, but so too did death. He was only 25 when in 1898 he finally succumbed to tuberculosis, but in those few years his artwork – sensuous, sometimes erotic and always subtle – sent waves through the establishment. He was already an accomplished pianist before turning to art in his late teens. Two years later, his works received a glowing notice in The Studio; leading pre-Raphaelite Burne Jones encouraged him to become a full-time artist. The youth from Ashley Road, Epsom, was on his way. In his last months, he lived at the Spread Eagle Hotel and completed designs for the Lysistrata of Aristophanes, considered erotic at the time and published in a privately printed edition.

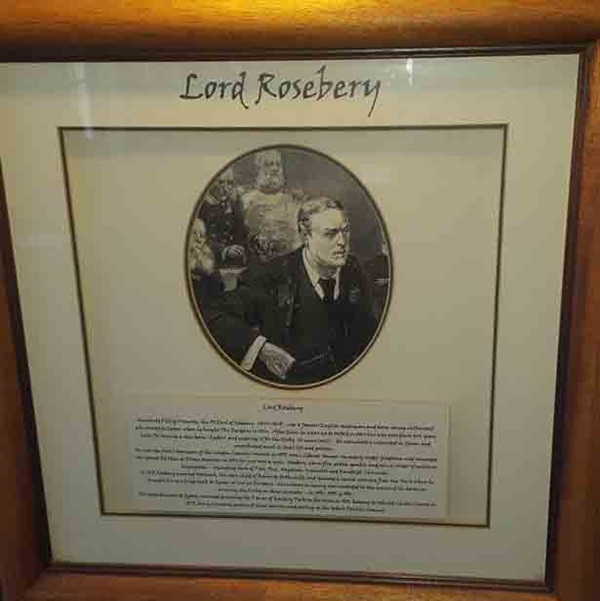

An illustration and text about Lord Roseberry

This text reads: Archibald Philip Primrose, the 5th Earl of Roseberry (1847–1929), was a famous English statesman and horse-racing enthusiast who moved to Epsom when he bought The Durdans in 1874. After Eton, he went up to Oxford in 1864 but was sent down two years later for buying a racehorse (Ladas) and entering it for the Derby (it came last!). He was greatly interested in Epsom and contributed much to local life and politics.

He was the first chairman of the London County Council in 1889, twice Liberal foreign secretary under Gladstone and succeeded the Grand Old Man as prime minister in 1894 for just over a year. Roseberry was a fine public speaker and also a writer of political biographies – including those of Pitt, Peel, Napoleon, Cromwell and Randolph Churchill.

In 1878, Roseberry married Hannah, the only child of Baron de Rothschild, and received a lavish welcome from the town when he brought his new bride back to Epsom to live at Durdans. His interest in racing was rewarded by the success of his horses in winning the Derby on three occasions – in 1894, 1895 and 1905.

His contributions to Epsom included donating the 11 acres of Roseberry Park to the town in 1913, helping to rebuild Christ Church in 1879, being a leading patron of local societies and serving on the Urban District Council.

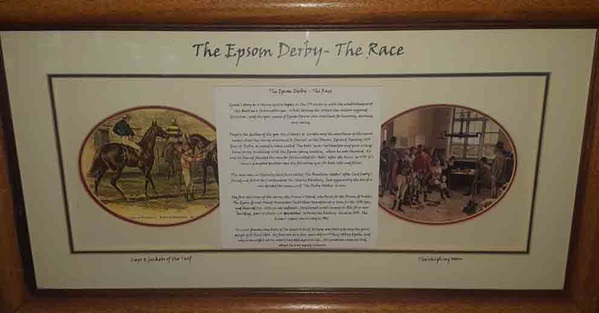

Illustrations and text about the Epsom Derby

The text reads: Epsom’s story as a racing centre began in the 17th century with the establishment of the town as a fashionable spa. While taking the waters, the visitors required diversions, and the open spaces of Epsom Downs were excellent for hunting, coursing and racing.

Despite the decline of the spa, the closeness to London and the excellence of the course meant that the racing continued to flourish on the Downs. Edward Stanely, 12th Earl of Derby, occupied a house called The Oaks near Carlshalton and gave a large house party to coincide with the Epsom spring meeting, where he was steward. He and his friends founded the race for fillies called the Oaks, after the house, in 1779; its success prompted another race the following year for both colts and fillies.

This new race could easily have been called The Bunbury Stakes, after Lord Derby’s friend and fellow turf enthusiast Sir Charles Bunbury, but apparently the toss of a coin decided the name, and The Derby Stakes it was.

The first structure of the course, the Prince’s Stand, was built for the Prince of Wales. The Epsom Grand Stand Association built their grandstand in time for the 1530 race, and their edifice, with period additions, functional until cleared in 1926 for a new building, part of which was demolished to build the Roseberry stand in 1959. The Queen’s stand was erected in 1992.

The most famous racehorse of the English turf, Eclipse, was foaled during the great eclipse of 1 April 1764. He first ran as a five-year-old on 3 May 1769 at Epsom, and was so successful no-one would lay odds against him. His greatness came at stud, where he sired many winners.

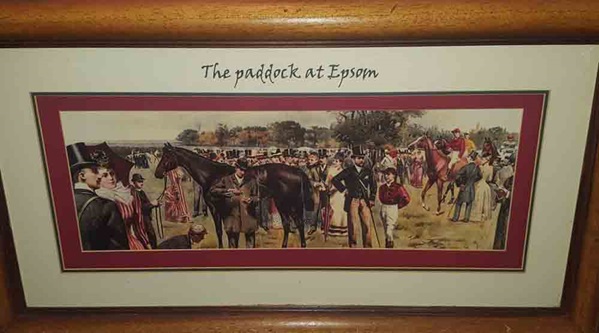

An illustration of the paddock at Epsom

Photographs of royalty watching the races

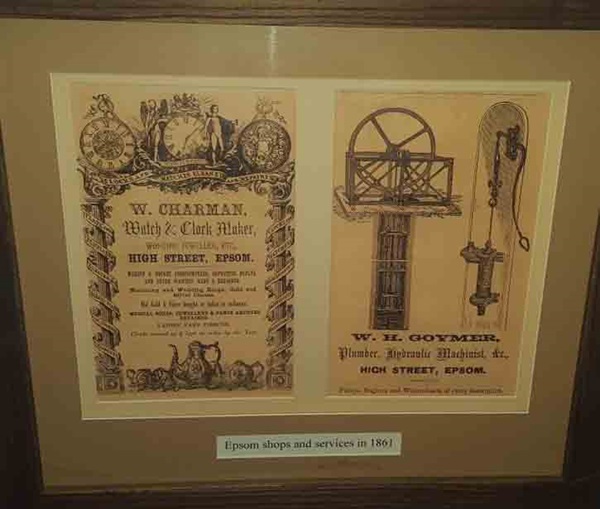

Posters advertising Epsom shops and services in 1861

An illustration of Durdans, the Epsom seat of the Right Hon. the Earl of Roseberry

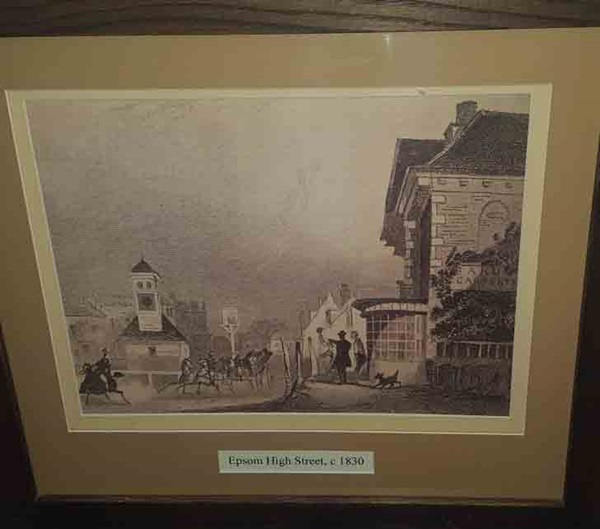

An illustration of Epsom High Street, c1830

External photograph of the building – main entrance