Pub history

The Admiral Byng

This is named after the admiral who had a house built at Wrotham Park, near Potters Bar, in 1754. Shortly after, he was shot (on government orders) as a scapegoat for the failure of the Minorca campaign – to encourage the others.

186–192 Darkes Lane, Potters Bar, Hertfordshire, EN6 1AF

This is named after the admiral who had a house built at Wrotham Park, near Potters Bar, in 1754. Shortly after, he was shot (on government orders) as a scapegoat for the failure of the Minorca campaign – to encourage the others.

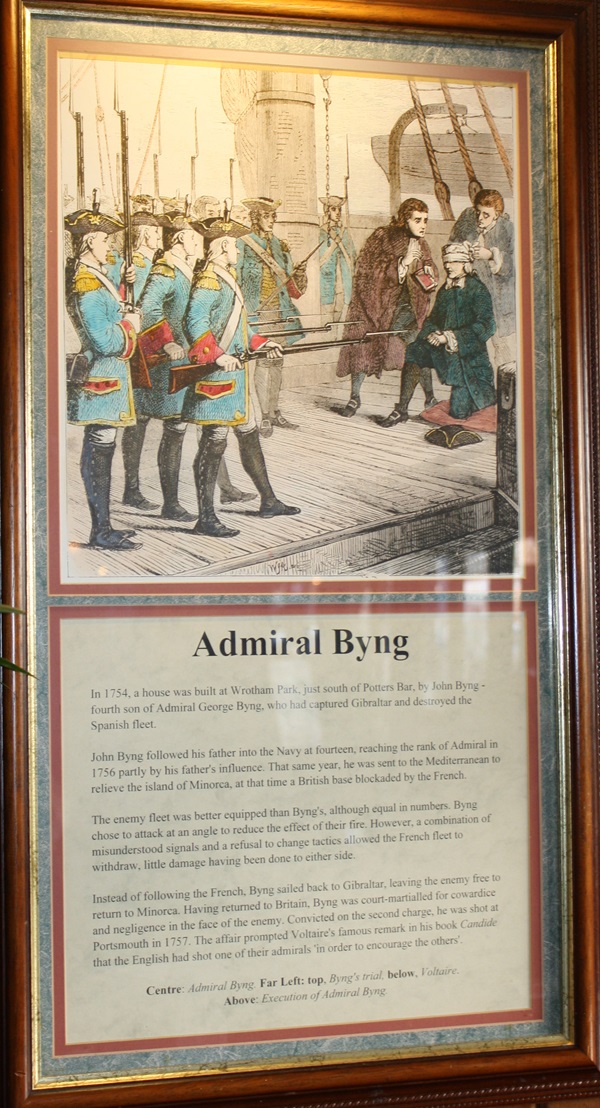

Illustrations and text about Admiral Byng.

The text reads: In 1754, a house was built at Wrotham Park, just south of Potters Bar, by John Byng – fourth son of Admiral George Byng, who had captured Gibraltar and destroyed the Spanish fleet.

John Byng followed his father into the Navy at fourteen, reaching the rank of Admiral in 1756 partly by his father’s influence. That same year, he was sent to the Mediterranean to relieve the island of Minorca, at that time a British base blockaded by the French.

The enemy fleet was better equipped than Byng’s, although equal in numbers. Byng chose to attack at an angle to reduce the effect of their fire. However, a combination of misunderstood signals and refusal to change tactics allowed the French fleet to withdraw, little damage having been done to either side.

Instead of following the French, Byng sailed back to Gibraltar, leaving the enemy free to return to Minorca. Having returned to Britain, Byng was court-martialled for cowardice and negligence in the face of the enemy. Convicted on the second charge, he was shot at Portsmouth in 1757. The affair prompted Voltaire’s famous remark in his book Candide that the English had shot one of their admirals in order to encourage the others.

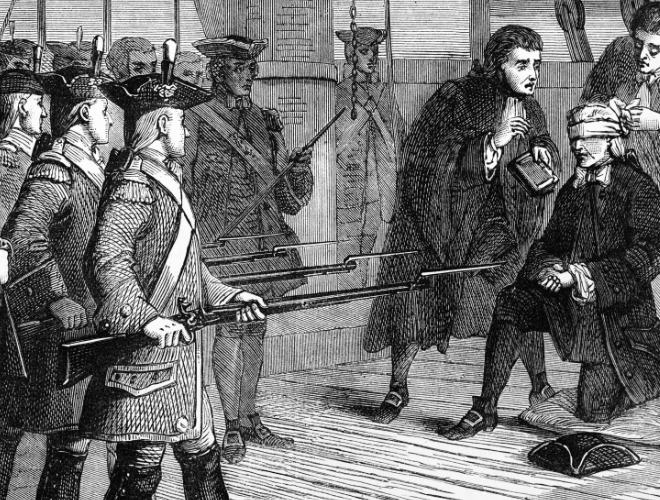

Above: Execution of Admiral Byng.

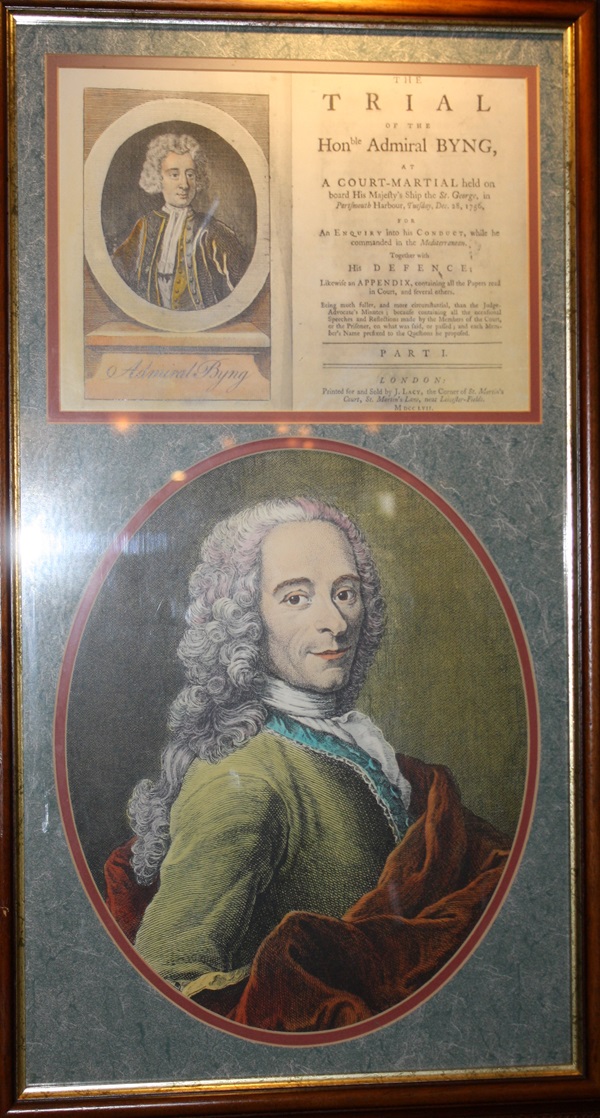

Centre: Admiral Byng

Far left: top, Byng’s trial, below, Voltaire

An illustration and text about John Heywood.

The text reads: A friend of the statesman and martyr Thomas More, John Heywood was a visitor to More Hall, at North Mymms. Heywood married More’s niece, and was introduced by him to Henry VIII’s daughter, Mary Tudor, possibly during the royal visit to More Hall.

Heywood became Mary’s music teacher, remaining loyal to her after she had been disinherited by Henry when he divorced her mother, Catherine of Aragon. A loyal Catholic, Heywood later went into exile when the Protestant Queen Elizabeth succeeded to the throne.

As well as a musician, John Heywood was an important literary figure, one of the first writers of English stage comedy.

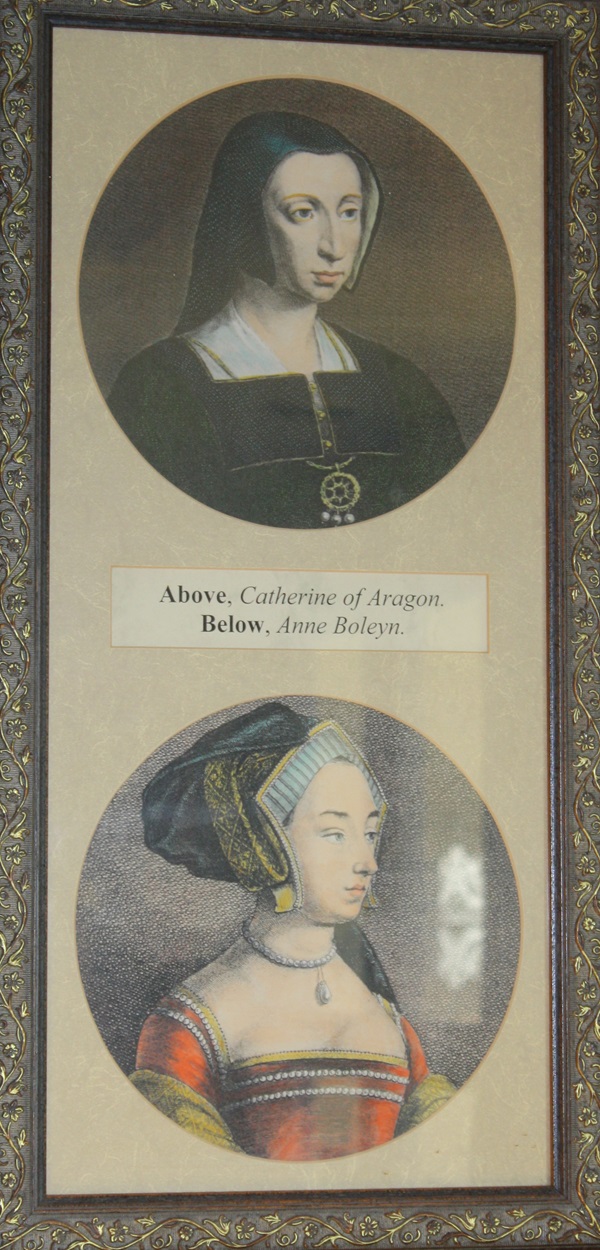

Prints of Catherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn.

Prints of King Henry VIII and Mary Tudor, the daughter he disinherited.

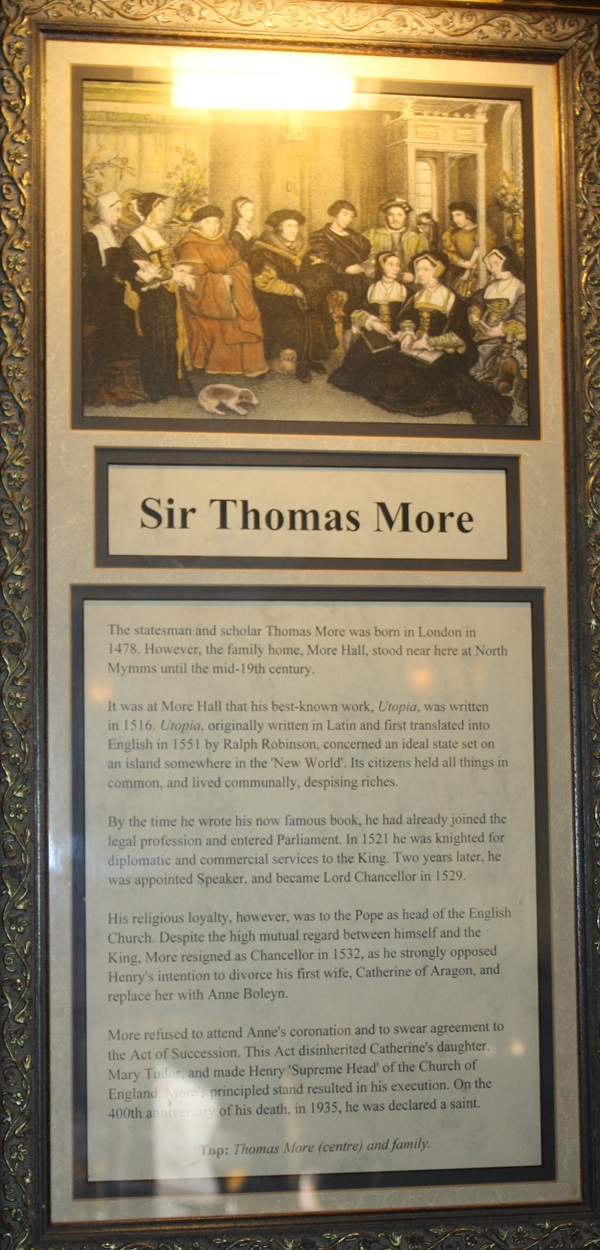

A print and text about Sir Thomas Moore.

The text reads: The statesman and scholar Thomas More was born in London in 1478. However, the family home, More Hall, stood near here at North Mymms until the mid-19th century.

It was at More Hall that his best-known work, Utopia, was written in 1516. Utopia, originally written in Latin and first translated into English in 1551 by Ralph Robinson, concerned an ideal state set on an island somewhere in the New World. Its citizens held all things in common, and lived communally, despising riches.

By the time he wrote his now famous book, he had already joined the legal profession and entered Parliament. In 1521 he was knighted for diplomatic and commercial services to the King. Two years later, he was appointed Speaker, and became Lord Chancellor in 1529.

His religious loyalty, however, was to the Pope as head of the English Church. Despite the high mutual regard between himself and the King, More resigned as Chancellor in 1532, as he strongly opposed Henry’s intention to divorce his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, and replace her with Anne Boleyn.

More refused to attend Anne’s coronation and to swear agreement to the Act of Succession. This Act disinherited Catherine’s daughter, Mary Tudor, and made Henry the Supreme Head of the Church of England. More’s principled stand resulted in his execution. On the 400th anniversary of his death, in 1935, he was declared a saint.

Top: Thomas More (centre) and family.

A miniature model of the HMS Victory, followed by text.

The text reads: Nelson’s Victory, laid down at Chatham in 1750, was the fifth of His Majesty’s Ships to bear that name. She took 15 years to build, and was launched on 7 May 1765. She weighed 2,162 tons, carried 108 guns, and a crew of 837 men.

The Victory first saw action in 1778, and was in the thick of it on three further occasions before she was commanded by Admiral Sir John Jervis in the Battle of Cape St Vincent in 1797. She was then given to Admiral Lord Nelson upon his appointment to Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean in 1803. Apart from one or two brief periods, Lord Nelson spent the rest of his life on board.

In 1805, Admiral Nelson sailed out of Portsmouth in Victory, and pursued the combined French and Spanish fleets as they headed from Cadiz for the Straits of Gibraltar, seeking to enter the Mediterranean. The French Admiral Villeneuve changed his mind, and his course, and turned for safety back towards Cadiz, only to encounter Nelson sailing with the wind behind him. Although smaller and fewer, the English fleet was a superior fighting force, and the advantage of the wind did the rest.

Nelson, with the Victory fighting at close quarters, was conducting the battle from an exposed position on the quarterdeck when he was hit by a musket ball.

Victory went into battle only once more, in 1812, before being used as a floating utility until she was moved to dry dock in 1922. She is preserved at Portsmouth, looking, to this day, as she would have appeared at Trafalgar 1805.

Text about the HMS Bounty.

The text reads: Before her involvement in the world’s most famous mutiny, HMS Bounty was a small and unimportant merchantman. She weighed only 220 tons, and was 90 feet from stem to stem. Under her 33 year old Captain, William Bligh, she sailed from Bristol for Tahiti in 1787 to load breadfruit for the West Indian plantations.

Bligh reached Tahiti despite gales and high seas, and an unruly element among his 44 crew, by virtue of his navigational brilliance, and strict (but not excessive) discipline. The bounty anchored for 6 months while the breadfruit was gathered, allowing the crew time to enjoy themselves, to the point where some of them wanted to stay. Bligh managed to force them back to sea once the Bounty was loaded and provisioned, but the men mutinied under Bligh’s lieutenant Fletcher Christian. Bligh was set adrift in the ship’s launch. 18 of the crew chose to take their chances with the Captain rather than the mutineers.

Bligh managed to sail 3,600 miles, and reach Timor, losing only one of his men on the way. He arrived in England to a hero’s welcome, and an utter determination to bring Fletcher Christian and his fellow mutineers to justice.

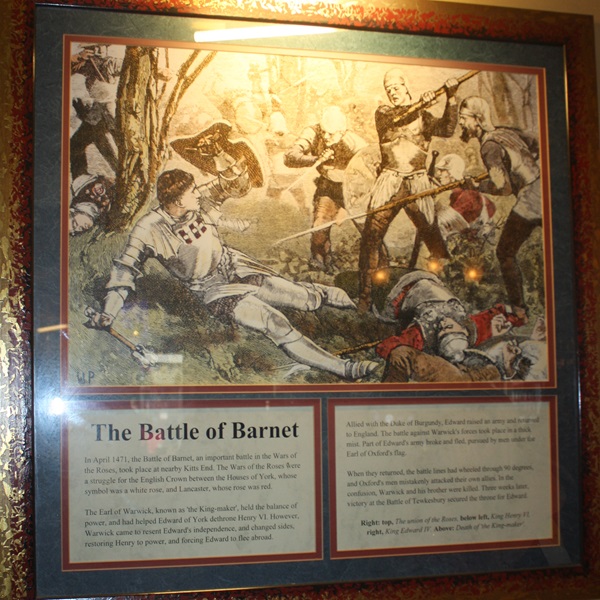

An illustration and text about the battle of Barnet.

The text reads: In April 1471, the Battle of Barnet, an important battle in the Wars of the Roses, took place at nearby Kitts End. The Wars of the Roses were a struggle for the English Crown between the Houses of York, whose symbol was a white rose, and Lancaster, whose rose was red.

The Earl of Warwick, known as the King-maker, held the balance of power, and had helped Edward of York dethrone Henry VI. However, Warwick came to resent Edward’s independence, and changed sides, restoring Henry to power, and forcing Edward to flee abroad.

Allied with the Duke of Burgundy, Edward raised an army and returned to England. The battle against Warwick’s forces took place in a thick mist. Part of Edward’s army broke and fled, pursued by men under the Earl of Oxford’s flag.

When they returned, the battle lines had wheeled through 90 degrees and Oxford’s men mistakenly attacked their own allies. In the confusion, Warwick and his brother were killed. Three weeks later, victory at the Battle of Tewkesbury secured the throne for Edward.

Right: top, The union of the Roses, below left, King Henry VI, right, King Edward IV

Above: Death of the King-maker.

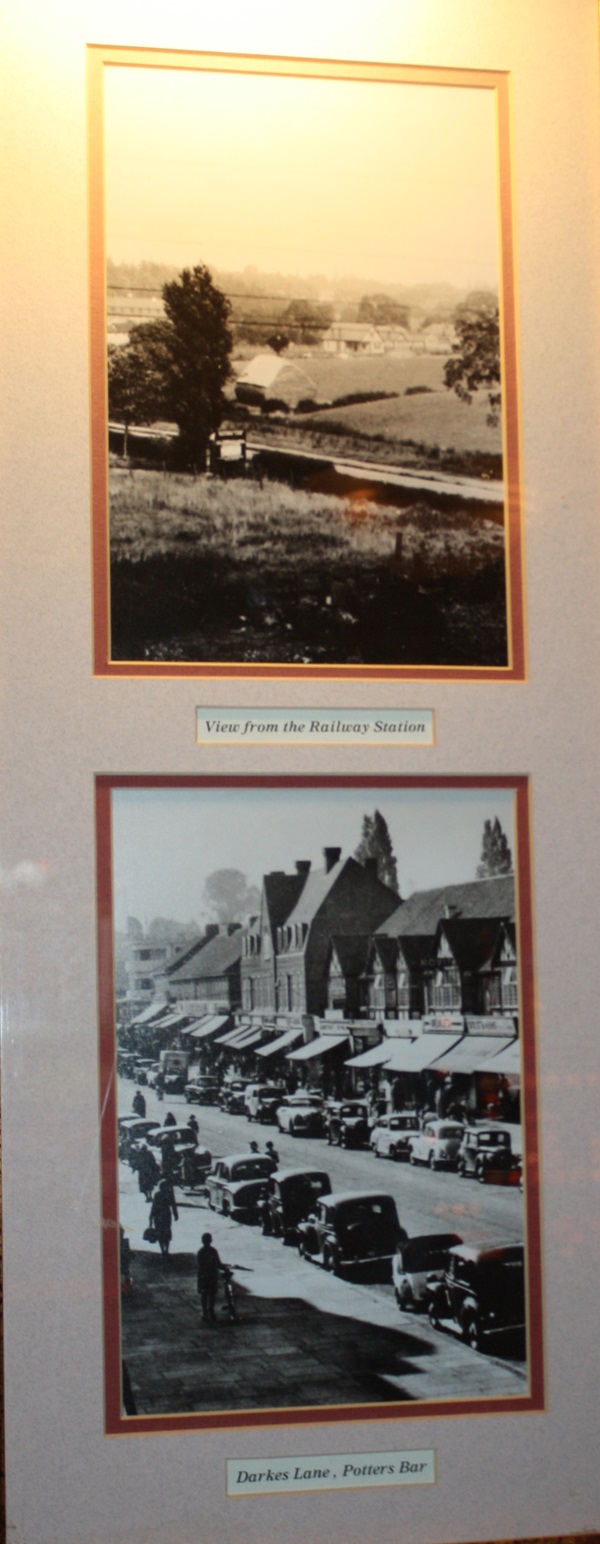

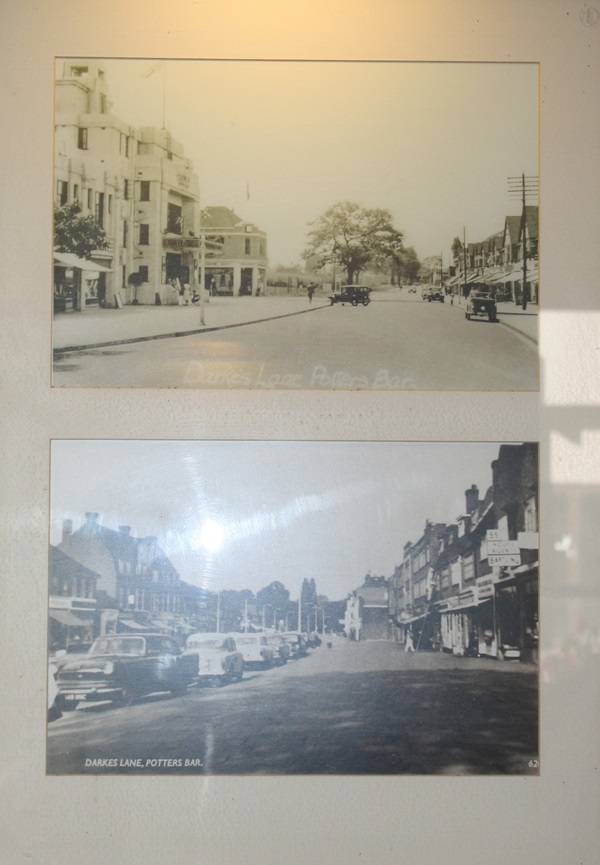

Illustrations, prints and text about the history of Potters Bar.

The text reads: Potters Bar High Street originated as a clearing in the thickly-wooded Enfield Chase, which became a Royal Forest and a favourite hunting-ground during the 14th century. For hundreds of years there was little traffic here, perhaps because of the outlaws, wolves, and wild boar which infested the area.

Change came in the 17th century, with the building of the Great North Road. Financed by tolls, the improvised road maintenance led to an increase in travellers, and by the 1830s, 15 stage-coaches a day passed along the High Street. Some were passenger vehicles, or long-distance mail coaches, others were slow, cumbersome goods-wagons. The Robin Hood and Little John Inn was built to service the passengers and supply a change of horses.

The arrival of the railway brought further change. In 1850 the Great Northern Railway Company opened their line from London to Peterborough, passing under the Great North Road via Potters Bar tunnel, nearly three-quarters of a mile long. Potters Bar Station was an afterthought, as the company was mainly concerned with long-distance business.

The railway builders, known as navvies from their days as builders of canals, or navigations, were housed in camps. Their needs were served by a pub called The Pilot Engine House, (later the local Red Cross headquarters).

A selection of photographs of Potters Bar.

Top: View from the railway station

Bottom: Darkes Lane.

The view of the station, c1910

Top: St John’s Church, c1908

Bottom: National School, 1905.

Darkes Lane.

Top: North End, 1912

Bottom: Northaw Place, c1910.

North End, c1920.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.

Extract from Wetherspoon News Summer 2017.