Pub history

Rose & Crown

This has long been a fixture on Maldon’s main shopping street. Flanked by several grade II listed properties, the building is said to be ‘early 16th century’, with ‘alterations to its front in the 18th and 19th century’. It is recorded as The Rose and Crown in the list of Maldon inns included in some of the earliest local trade directories, published in the 1780s. At that time, its licensee was Thomas King.

109 High Street, Maldon, Essex, CM9 5EP

Text and photographs about the history of this building.

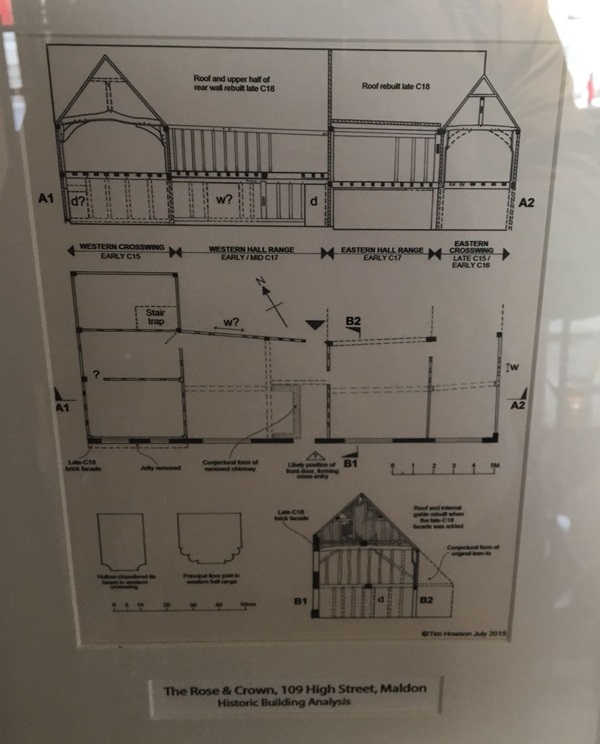

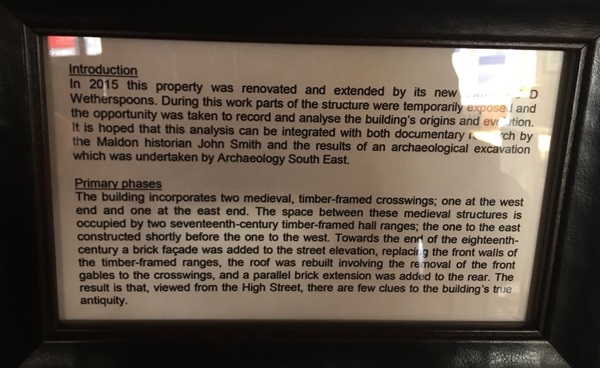

The text reads: In 2015 this property was renovated and extended by its new owner J D Wetherspoon. During this work parts of the structure were temporarily exposed and the opportunity was taken to record and analyse the building’s origins and evolution. It is hoped that this analysis can be integrated with both documentary research by the Maldon historian John Smith and the results of an archaeological excavation which was undertaken by Archaeology South East.

The building incorporates two medieval, timber-framed crosswings; one at the west end and one at the east end. The space between these medieval structures is occupied by two 17th century timber-framed hall ranges; the one to the east constructed shortly before the one to the west. Towards the end of the eighteenth-century a brick façade was added to the street elevation, replacing the front walls of the timber-framed ranges, the roof was rebuilt involving the removal of the front gables to the crosswings, and a parallel brick extension was added to the rear. The result is that, viewed from the High Street, there are few clues to the building’s true antiquity.

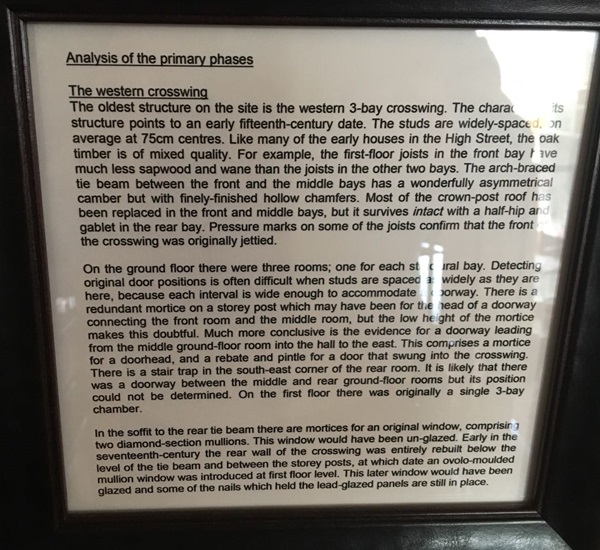

The text reads: The oldest structure on the site is the western 3-bay crosswing. The characteristics of its structure points to an early fifteenth-century date. The studs are widely-spaced, on average at 75cm centres. Like many of the early houses in the High Street, the oak timber is of mixed quality. For example, the first floor joists in the front bay have much less sapwood and wane than the joists in the other two bays. The arch-braced tie beam between the front and the middle bays has a wonderfully asymmetrical camber but with finely-finished hollow chamfers. Most of the crown-post roof has been replaced in the front and middle bays, but it survives intact with a half-hip and gablet in the rear bay. Pressure marks on some of the joists confirmed that the front of the crosswing was originally jettied.

On the ground floor there were three rooms; one for each structural bay. Detecting original door positions is often difficult when studs are spaced as widely as they are here, because each interval is wide enough to accommodate a doorway. There is a redundant mortice on a storey post with may have been for the head of a doorway connecting the front room and the middle room, but the low height of the mortice makes this doubtful. Much more conclusive is the evidence for a doorway leading from the middle ground-floor room into the hall to the east. This comprises a mortice for a door head, and a rebate and pintle for a door that swung into the crosswing. There is a stair trap in the south-east corner of the rear room. It is likely that there was a doorway between the middle and rear ground floor rooms but its position could not be determined. On the first floor there was originally a single 3-bay chamber.

In the soffit to the rear tie beam there are mortices for an original window, comprising of two diamond-section mullions. This window would have been un-glazed. Early in the seventeenth-century the rear wall of the crosswing was entirely rebuilt below the level of the tie beam and between the storey posts, at which date an ovolo-moulded mullion window was introduced at first floor level. This later window would have been glazed and some of the nails which held the lead-glazed panels are still in place.

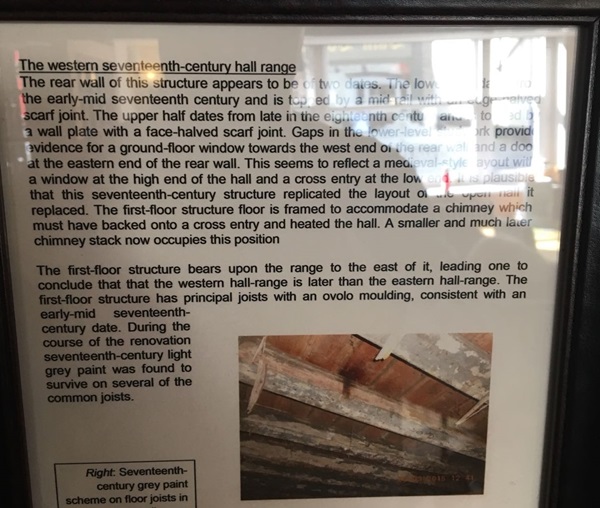

The text reads: The first-floor structure bears upon the range to the east of it, leading one to conclude that the western hall-range is later than the eastern hall-range. The first-floor structure has principal joists with an ovolo moulding, consistent with an early-mid 17th century date. During the course of the renovation 17th century light grey paint was found to survive on several of the common joists.

Right: 17th century grey paint scheme on floor joists in the western hall range.

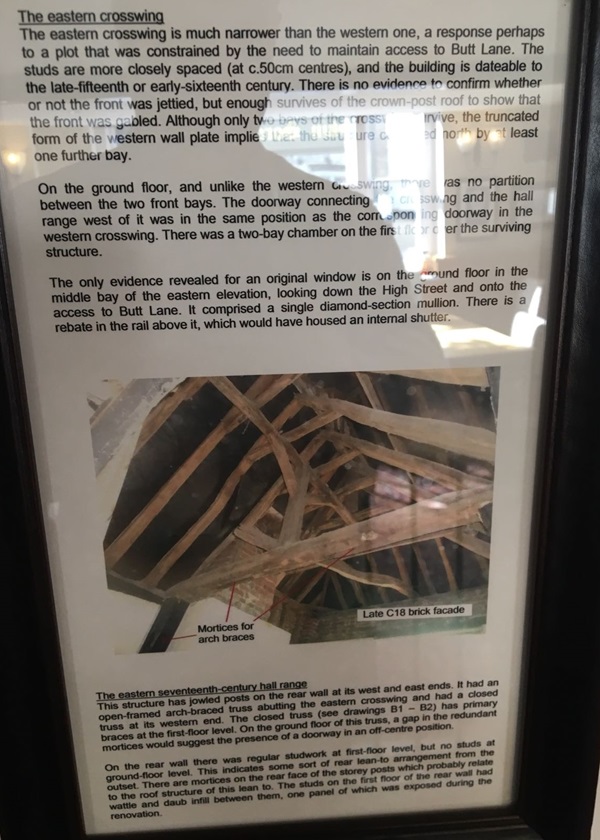

The text reads: The eastern crosswing is much narrower than the western one, a response perhaps to a plot that was constrained by the need to maintain access to Butt Lane. The studs are more closely spaced (at 50cm centres), and the building is dateable to the late-fifteenth or early-sixteenth century. There is no evidence to confirm whether or not the front was jettied, but enough survived of the crown-post roof to show that the front was gabled.

On the ground floor, and unlike the western crosswing, there was no partition between the two front bays. The doorway connecting the crosswing and the hall range west of it was in the same position as the corresponding doorway in the western crosswing. There was a two-bay chamber on the first floor over the surviving structure.

The only evidence revealed for an original window is on the ground floor in the middle bay of the eastern elevation, looking down the High Street and onto the access to Butt Lane. It comprised a single diamond-section mullion. There is a rebate in the rail above it, which would have housed an internal shutter.

The eastern seventeenth-century hall range: This structure has jowled posts on the rear wall at its west and east ends. It had an open-framed arch-braced truss abutting the eastern crosswing and had a closed truss at its western end. The closed truss (see drawings B1-B2) has primary braces at the first floor level. On the ground floor of this truss, a gap in the redundant mortices would suggest the presence of a doorway in an off-centre position.

On the rear wall there was regular studwork at first floor level, but no studs at ground floor level. This indicates some sort of rear lean-to arrangement from the outset. There are mortices on the rear face of the storey posts which probably relate to the roof structure of this lean to. The studs on the first floor of the rear wall had wattle and daub infill between them, one panel of which was exposed during the renovation.

An historic building analysis of The Rose & Crown, 109 High Street, Maldon.

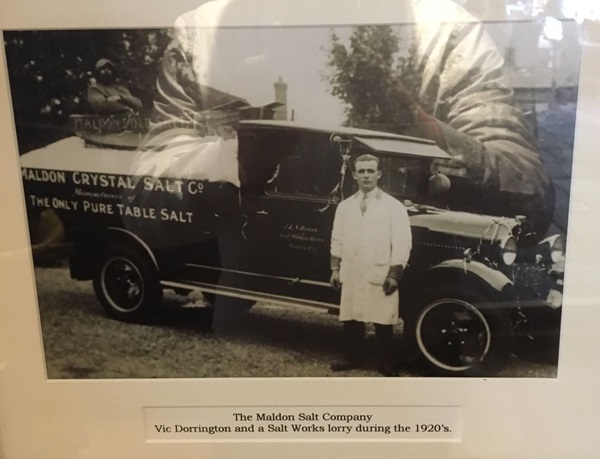

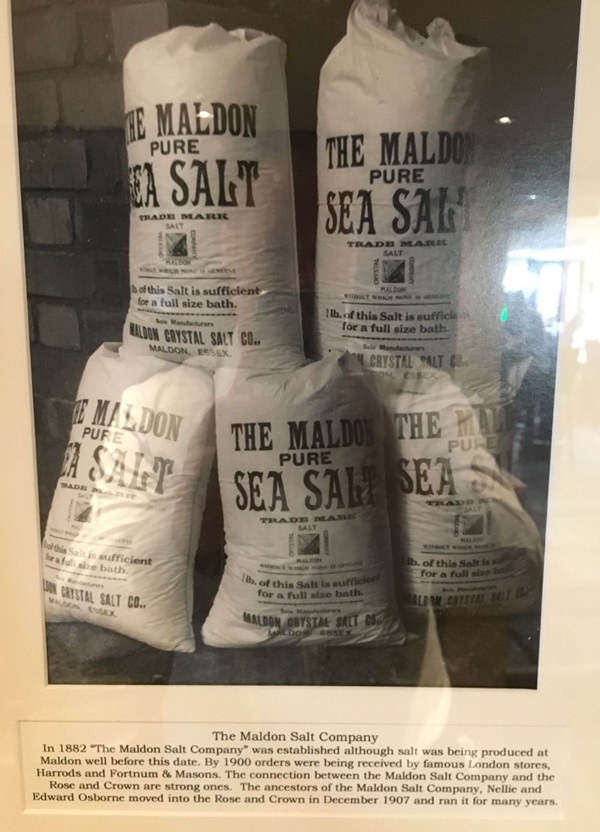

A photograph and text about The Maldon Salt Company.

The text reads: In 1882 The Maldon Salt Company was established although salt was being produced at Maldon well before this date. By 1900 orders were being received by famous London stores, Harrods and Fortnum & Masons. The connection between the Maldon Salt Company and the Rose and Crown are strong ones. The ancestors of the Maldon Salt Company, Nellie and Edward Osbourne moved into the Rose and Crown in December 1907 and ran it for many years.

A photograph of Vic Dorrington and a Salt Works lorry during the 1920s.

External photograph of the building – main entrance.